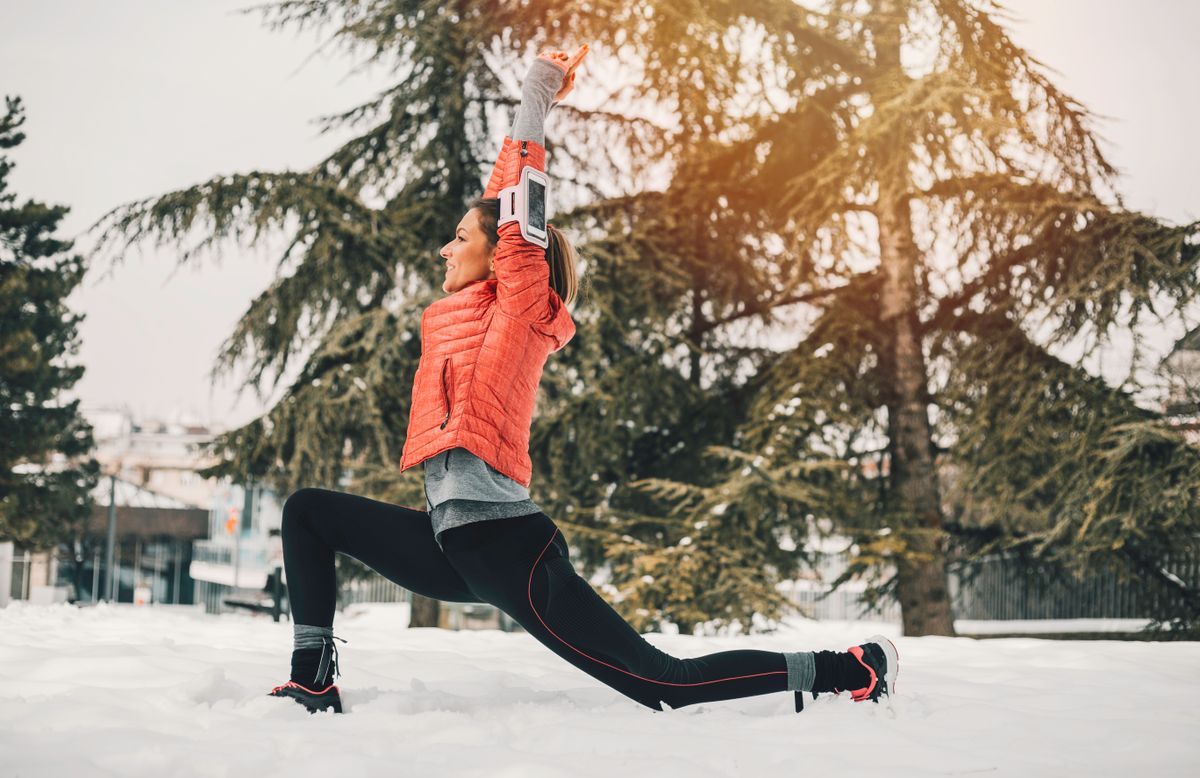

El invierno puede ser una época difícil para mantenerse motivado y tener pensamientos positivos. Los días más cortos y las temperaturas gélidas son especialmente difíciles para mí porque me encanta el sol y estar al aire libre. Aunque todavía trato de salir y salir a correr cuando el clima lo permite, a menudo me siento deprimido y tiendo a pensar negativamente.

Si bien los terapeutas profesionales no son rival para ChatGPT, en caso de necesidad, a menudo utilizo ChatGPT para explorar estrategias para desarrollar la fortaleza mental mientras desafío los pensamientos negativos durante los meses de invierno.

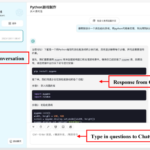

Aprecio el modo de voz avanzado de ChatGPT porque los usuarios pueden tener una conversación humana sobre cualquier cosa, incluso pensamientos desanimados y desmotivados. Esto es lo que sucedió cuando compartí mis pensamientos con ChatGPT y las sugerencias que me dio.

1. Considere las alegrías invernales simples

Inmediato: “¿Qué pequeños placeres o actividades acogedoras puedes sugerir para traer calidez y alegría durante la temporada de invierno?”

Objetivo: Identificar alegrías sencillas que mejoran la satisfacción diaria y contrarrestan la tristeza invernal.

Prefiero ChatGPT Advanced Voice “Sol” porque la IA es relajada y tranquila. Chatear con esta IA se siente como si estuviera hablando con un buen amigo que está lleno de ideas y tiene la capacidad de mantenerse tranquilo independientemente de cualquier situación que le presente.

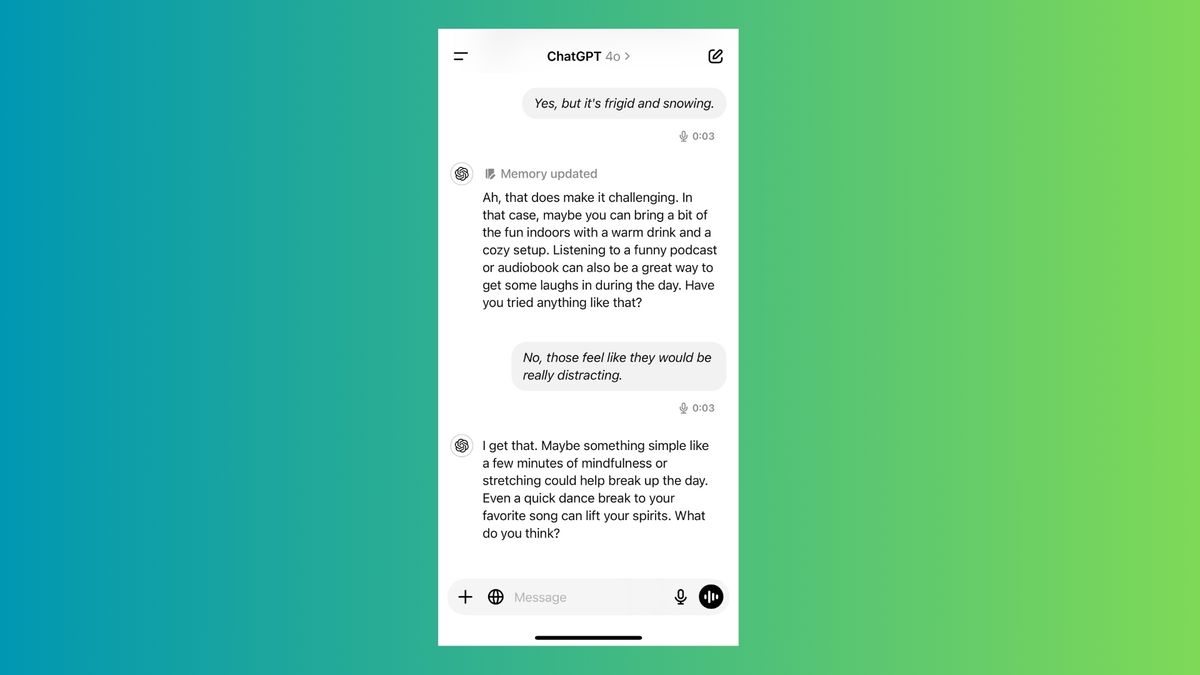

Cuando mencioné que estaba luchando por estar atrapado en el interior a pesar de la hermosa nieve que caía afuera, me sugirió practicar la atención plena y reflexionar sobre mi día ideal de invierno.

La meditación de atención plena implica centrarse en el momento presente, reconociendo pensamientos y sentimientos sin juzgar. Le pedí orientación a ChatGPT sobre cómo iniciar una práctica de atención plena.

Proporcionó un enfoque paso a paso, que incluía reservar tiempo dedicado, encontrar un espacio tranquilo y concentrarse en la respiración. Incluso me dijo que la atención plena podría ser un estiramiento rápido o una pausa para bailar durante el día para levantarme el ánimo.

2. Replantear los pensamientos negativos

Inmediato: “Esto es lo que me molesta. ¿Puedes darme una charla de ánimo y explicarme cómo puedo mantener una actitud positiva?”

Objetivo: Para inspirar la planificación de actividades agradables que combatan los sentimientos de estancamiento y le brinden algo que esperar.

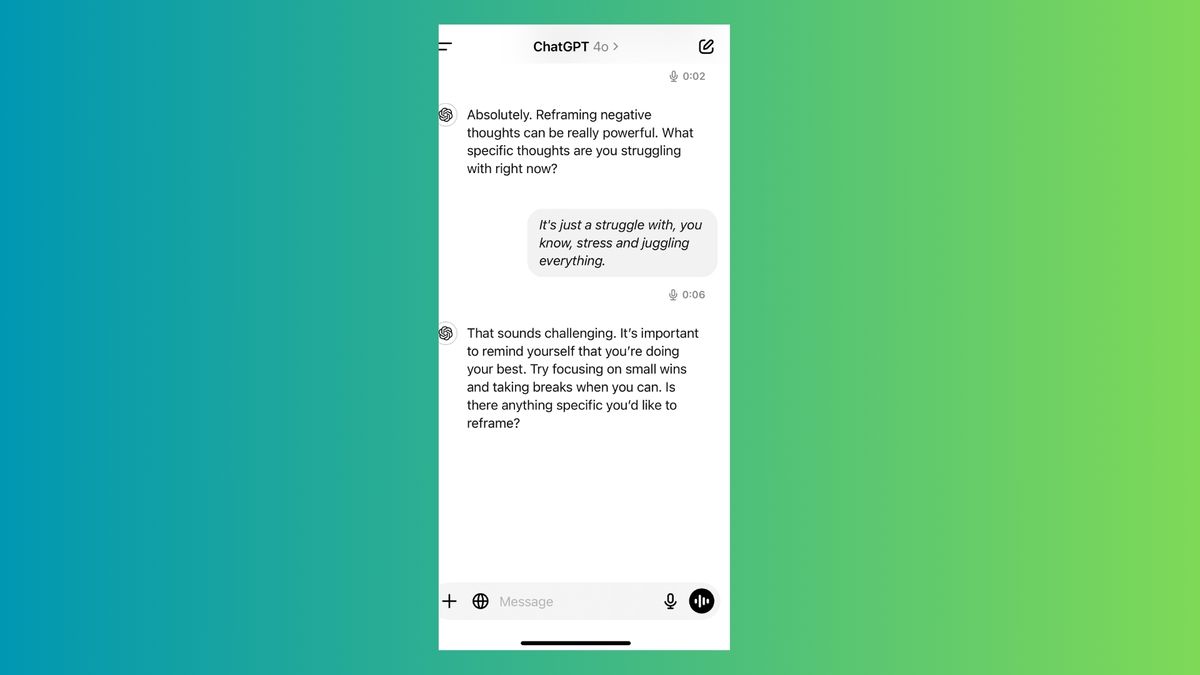

Los patrones de pensamiento negativos pueden ser omnipresentes durante los meses de invierno. Busqué consejo en ChatGPT sobre lo que puedo hacer para alejar mis pensamientos de mi actual mentalidad negativa y pesimista hacia algo más positivo.

Además de compartir formas de replantear mis pensamientos, la IA también agregó que lo estaba “yendo muy bien” y que era una especie de máquina de exagerar para mí. Me sentí bien tener una charla de ánimo al mediodía, especialmente porque no me la esperaba. El modo de voz avanzado ChatGPT es excelente cuando necesitas una perspectiva más positiva. Simplemente escuchar: “¡Tú puedes hacer esto!” incluso desde un chatbot, es excepcionalmente estimulante.

La aplicación de la técnica de ChatGPT me permitió cambiar mi forma de pensar de “no puedo manejar esto” a “puedo aprender a manejar este desafío”, fomentando la resiliencia y una perspectiva más positiva.

3. Realizar actividad física

Inmediato: “En verano disfruto [list your favorite activities]. ¿Puedes sugerir actividades similares que pueda disfrutar durante los meses de invierno?”

Objetivo: Explorar formas de mejorar su apreciación de la temporada de invierno y crear una lista de opciones para mejorar su estado de ánimo.

Se sabe que el ejercicio físico mejora el estado de ánimo y reduce la ansiedad. Siempre me ha gustado correr y el ejercicio físico en general, pero incluso hacer las cosas que amamos puede resultar difícil cuando estamos abrumados por pensamientos negativos.

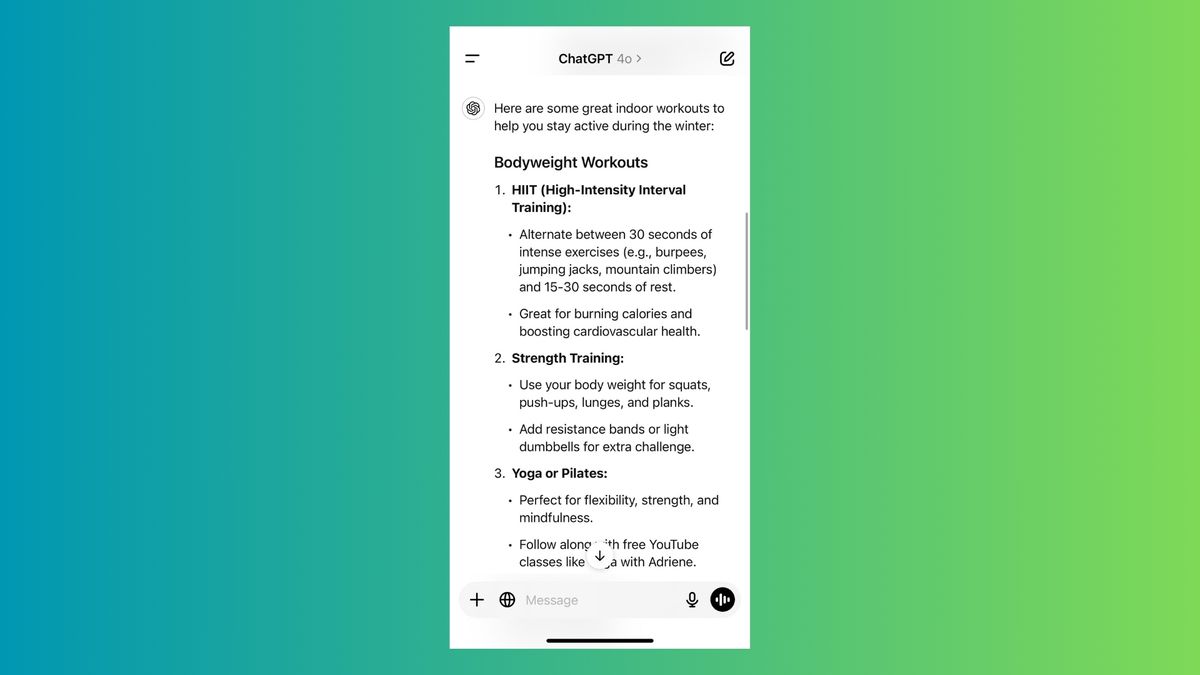

Por eso le pedí a ChatGPT sugerencias de ejercicios en interiores adecuados para el invierno. Tengo una cinta de correr, pero buscaba actividades que me ayudaran a tranquilizarme.

Recomendó actividades como yoga, ejercicios de peso corporal y rutinas de baile que se pueden realizar en casa. Desde HIIT (entrenamiento en intervalos de alta intensidad) hasta Pilates y entrenamiento de fuerza, ChatGPT ofreció una variedad de formas de incorporar estos ejercicios a mi rutina.

Esto no sólo mejoró mi salud física, sino que también mejoró significativamente mi estado de ánimo, combatiendo eficazmente la tristeza invernal.

4. Establecer una práctica de gratitud

Inmediato: “¿Puedes ayudarme a enumerar diez cosas por las que estar agradecido en este momento? Para cada una, explica por qué es importante o significativa”.

Objetivo: Cambiar el enfoque de la negatividad a la positividad, mejorando el estado de ánimo general mediante la práctica de la gratitud.

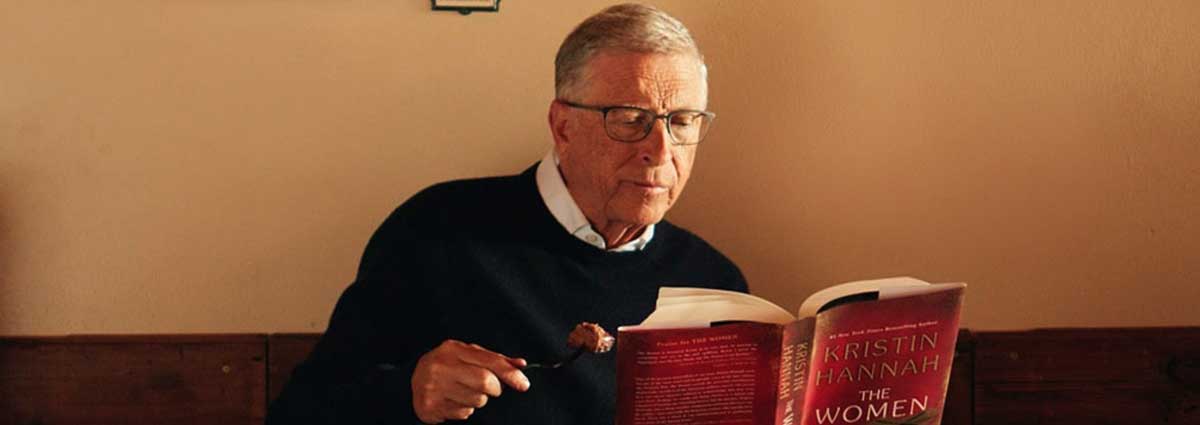

Habiendo experimentado la alegría de llevar un diario de gratitud, sé que tomar nota de las cosas por las que estoy agradecido cada día puede marcar una verdadera diferencia. En lugar de centrarme en las cosas que no puedo cambiar, poner énfasis en todo lo bueno que ya tengo hace maravillas con mi estado de ánimo.

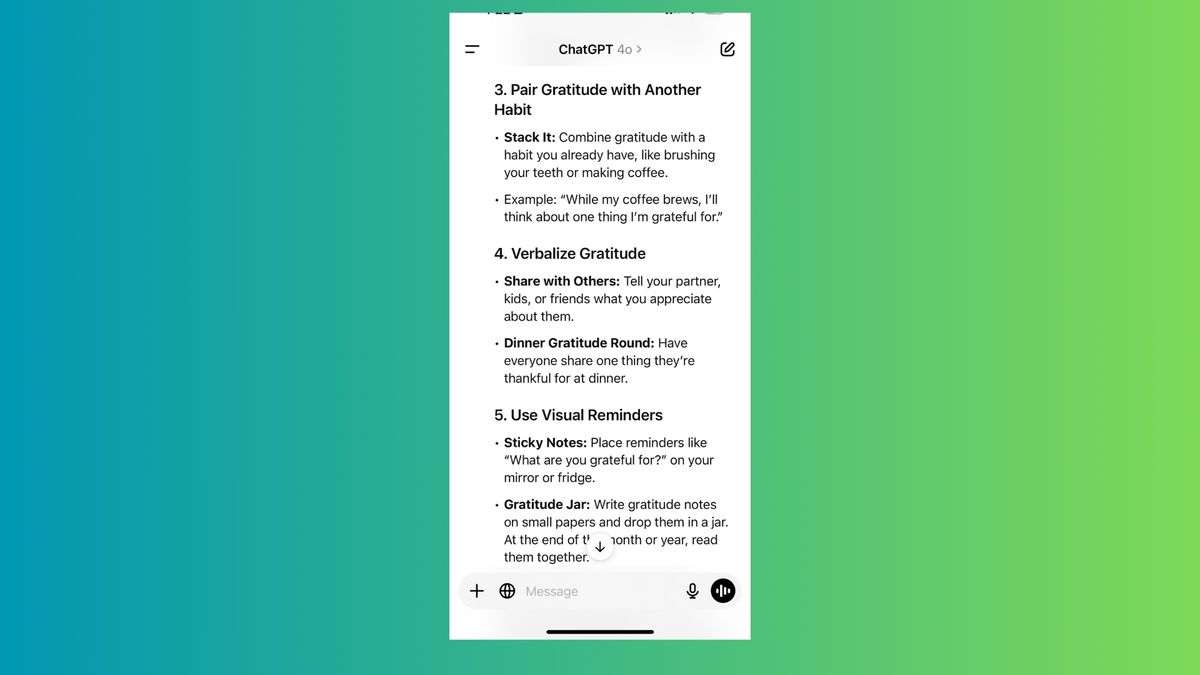

Sin embargo, ChatGPT llevó esta práctica un poco más allá al sugerirme que combine la gratitud con otro hábito. Esto fue un cambio de vida. Sugirió combinar la gratitud con un hábito que ya tengo, como tomar café. Por ejemplo, “Mientras se prepara el café, pensaré en algo por lo que estoy agradecido”.

Esta práctica me ayudó a apreciar los elementos positivos de mi vida, reduciendo el impacto de los pensamientos negativos y fomentando una perspectiva más optimista durante la temporada de invierno.

5. Establecer objetivos realistas

Inmediato: “Aquí están mis tres objetivos que quiero alcanzar para finales de este invierno. ¿Puedes describir los pasos que podría seguir para lograrlos?”

Objetivo: Ayudar a establecer metas alcanzables que proporcionen dirección y un sentido de propósito durante los meses de invierno.

Establecer y alcanzar metas pequeñas y realistas puede proporcionar una sensación de logro y propósito. He usado ChatGPT para ayudarme a establecer resoluciones y objetivos en mi lista de deseos de 5 años, pero consultar ChatGPT para conocer estrategias de establecimiento de objetivos para cada día me ayudó a mantenerme concentrado y organizado.

Lograr pequeñas metas cada día aumentó mi autoestima y me dio motivación a pesar de los días fríos y oscuros. Al utilizar ChatGPT como consultor para estrategias de establecimiento de metas, pude formular metas INTELIGENTES y establecer objetivos alcanzables.

Ya sea para dedicar tiempo a una manualidad que había descuidado o para intentar cocinar un plato nuevo, el apoyo de ChatGPT cada día ha cambiado las reglas del juego.

6. Planifica un día de cuidado personal

Inmediato: “¿Puede sugerirme ideas para una rutina enriquecedora de cuidado personal en invierno, incluidas actividades que me ayuden a sentirme mejor?”

Objetivo: Ayudar a establecer una rutina que priorice el bienestar y combata los desafíos estacionales.

Después de las fiestas, parece que todo el mundo vuelve a su rutina, lo que hace más difícil recuperarse del estrés y la ansiedad de los viajes, las cargas financieras o los eventos sociales incómodos que ocurrieron durante la temporada navideña.

El aislamiento social puede exacerbar los pensamientos negativos, por eso le pedí a ChatGPT ideas para mantener las conexiones sociales durante el invierno. Sugirió reuniones virtuales, unirse a comunidades en línea y programar visitas periódicas con amigos y familiares.

Si bien ya los hago, me surgió una nueva idea de consultarme más a menudo. Al hacerlo, es más probable que me sienta cómodo acercándome a conocidos, personas con las que podría convertirme en amigos más cercanos para el verano.

ChatGPT también me ayudó a comprender la importancia de participar en actividades que me ayuden a sentirme conectado, lo cual también es una forma de cuidado personal. Por esa razón, me he conectado más a menudo con nuestra vecina, que también es mamá.

7. Probar algo nuevo

Inmediato: “Esta es mi idea de un día de invierno perfecto, de principio a fin. Según mis recursos y mi situación actual, ¿pueden ayudarme a planificar algo similar?”

Objetivo: Inspirar una visión de felicidad y fomentar la incorporación de elementos de un día ideal a la vida real.

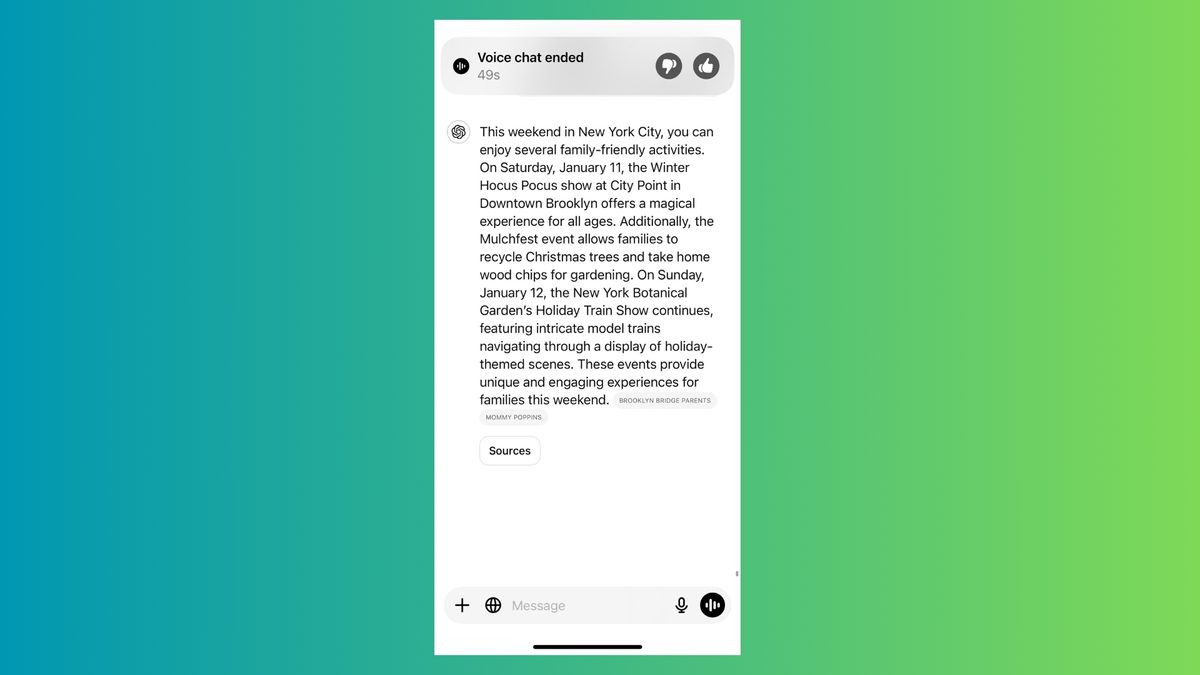

ChatGPT sugirió que una de las mejores formas de ahuyentar la tristeza es probar algo nuevo. Ya sea un viaje al parque de trampolines o una caminata en la nieve por los pintorescos bosques, probar nuevas actividades puede ayudar a romper la monotonía de un largo invierno.

Esta sugerencia me pareció muy personal. Sé que puedo adoptar rutinas que a veces me hacen funcionar en piloto automático, especialmente durante los días de semana. Me di cuenta de que cambiar las cosas y probar algo nuevo puede ser una de las mejores formas de romper con la previsibilidad de la vida durante el invierno. Le pedí ideas a ChatGPT y le di mi código postal para que pudiera brindarme ideas cerca de mí.

¿ChatGPT ayudó?

La utilización de ChatGPT como recurso ofreció estrategias prácticas para desarrollar la fuerza mental y desafiar los pensamientos negativos durante los meses de invierno.

Al implementar la meditación de atención plena, replantear pensamientos negativos, realizar actividad física, establecer una práctica de gratitud, establecer metas realistas, mantener conexiones sociales y buscar apoyo profesional, experimenté una mejora notable en mi bienestar mental.

Si bien la IA puede proporcionar una orientación valiosa, es esencial adaptar estas estrategias a las necesidades individuales y consultar a profesionales cuando sea necesario. Adoptar estas prácticas puede conducir a una mentalidad más resiliente, lo que le permitirá afrontar los desafíos del invierno con mayor facilidad y positividad.

Nota: Las estrategias mencionadas se basan en consejos generales y experiencia personal. Para obtener apoyo personalizado de salud mental, se recomienda consultar a un profesional autorizado.