Noticias

Rampant AI Cheating Is Ruining Education Alarmingly Fast

Published

9 meses agoon

Illustration: New York Magazine

Chungin “Roy” Lee stepped onto Columbia University’s campus this past fall and, by his own admission, proceeded to use generative artificial intelligence to cheat on nearly every assignment. As a computer-science major, he depended on AI for his introductory programming classes: “I’d just dump the prompt into ChatGPT and hand in whatever it spat out.” By his rough math, AI wrote 80 percent of every essay he turned in. “At the end, I’d put on the finishing touches. I’d just insert 20 percent of my humanity, my voice, into it,” Lee told me recently.

Lee was born in South Korea and grew up outside Atlanta, where his parents run a college-prep consulting business. He said he was admitted to Harvard early in his senior year of high school, but the university rescinded its offer after he was suspended for sneaking out during an overnight field trip before graduation. A year later, he applied to 26 schools; he didn’t get into any of them. So he spent the next year at a community college, before transferring to Columbia. (His personal essay, which turned his winding road to higher education into a parable for his ambition to build companies, was written with help from ChatGPT.) When he started at Columbia as a sophomore this past September, he didn’t worry much about academics or his GPA. “Most assignments in college are not relevant,” he told me. “They’re hackable by AI, and I just had no interest in doing them.” While other new students fretted over the university’s rigorous core curriculum, described by the school as “intellectually expansive” and “personally transformative,” Lee used AI to breeze through with minimal effort. When I asked him why he had gone through so much trouble to get to an Ivy League university only to off-load all of the learning to a robot, he said, “It’s the best place to meet your co-founder and your wife.”

By the end of his first semester, Lee checked off one of those boxes. He met a co-founder, Neel Shanmugam, a junior in the school of engineering, and together they developed a series of potential start-ups: a dating app just for Columbia students, a sales tool for liquor distributors, and a note-taking app. None of them took off. Then Lee had an idea. As a coder, he had spent some 600 miserable hours on LeetCode, a training platform that prepares coders to answer the algorithmic riddles tech companies ask job and internship candidates during interviews. Lee, like many young developers, found the riddles tedious and mostly irrelevant to the work coders might actually do on the job. What was the point? What if they built a program that hid AI from browsers during remote job interviews so that interviewees could cheat their way through instead?

In February, Lee and Shanmugam launched a tool that did just that. Interview Coder’s website featured a banner that read F*CK LEETCODE. Lee posted a video of himself on YouTube using it to cheat his way through an internship interview with Amazon. (He actually got the internship, but turned it down.) A month later, Lee was called into Columbia’s academic-integrity office. The school put him on disciplinary probation after a committee found him guilty of “advertising a link to a cheating tool” and “providing students with the knowledge to access this tool and use it how they see fit,” according to the committee’s report.

Lee thought it absurd that Columbia, which had a partnership with ChatGPT’s parent company, OpenAI, would punish him for innovating with AI. Although Columbia’s policy on AI is similar to that of many other universities’ — students are prohibited from using it unless their professor explicitly permits them to do so, either on a class-by-class or case-by-case basis — Lee said he doesn’t know a single student at the school who isn’t using AI to cheat. To be clear, Lee doesn’t think this is a bad thing. “I think we are years — or months, probably — away from a world where nobody thinks using AI for homework is considered cheating,” he said.

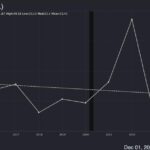

In January 2023, just two months after OpenAI launched ChatGPT, a survey of 1,000 college students found that nearly 90 percent of them had used the chatbot to help with homework assignments. In its first year of existence, ChatGPT’s total monthly visits steadily increased month-over-month until June, when schools let out for the summer. (That wasn’t an anomaly: Traffic dipped again over the summer in 2024.) Professors and teaching assistants increasingly found themselves staring at essays filled with clunky, robotic phrasing that, though grammatically flawless, didn’t sound quite like a college student — or even a human. Two and a half years later, students at large state schools, the Ivies, liberal-arts schools in New England, universities abroad, professional schools, and community colleges are relying on AI to ease their way through every facet of their education. Generative-AI chatbots — ChatGPT but also Google’s Gemini, Anthropic’s Claude, Microsoft’s Copilot, and others — take their notes during class, devise their study guides and practice tests, summarize novels and textbooks, and brainstorm, outline, and draft their essays. STEM students are using AI to automate their research and data analyses and to sail through dense coding and debugging assignments. “College is just how well I can use ChatGPT at this point,” a student in Utah recently captioned a video of herself copy-and-pasting a chapter from her Genocide and Mass Atrocity textbook into ChatGPT.

Sarah, a freshman at Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario, said she first used ChatGPT to cheat during the spring semester of her final year of high school. (Sarah’s name, like those of other current students in this article, has been changed for privacy.) After getting acquainted with the chatbot, Sarah used it for all her classes: Indigenous studies, law, English, and a “hippie farming class” called Green Industries. “My grades were amazing,” she said. “It changed my life.” Sarah continued to use AI when she started college this past fall. Why wouldn’t she? Rarely did she sit in class and not see other students’ laptops open to ChatGPT. Toward the end of the semester, she began to think she might be dependent on the website. She already considered herself addicted to TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and Reddit, where she writes under the username maybeimnotsmart. “I spend so much time on TikTok,” she said. “Hours and hours, until my eyes start hurting, which makes it hard to plan and do my schoolwork. With ChatGPT, I can write an essay in two hours that normally takes 12.”

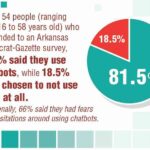

Teachers have tried AI-proofing assignments, returning to Blue Books or switching to oral exams. Brian Patrick Green, a tech-ethics scholar at Santa Clara University, immediately stopped assigning essays after he tried ChatGPT for the first time. Less than three months later, teaching a course called Ethics and Artificial Intelligence, he figured a low-stakes reading reflection would be safe — surely no one would dare use ChatGPT to write something personal. But one of his students turned in a reflection with robotic language and awkward phrasing that Green knew was AI-generated. A philosophy professor across the country at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock caught students in her Ethics and Technology class using AI to respond to the prompt “Briefly introduce yourself and say what you’re hoping to get out of this class.”

It isn’t as if cheating is new. But now, as one student put it, “the ceiling has been blown off.” Who could resist a tool that makes every assignment easier with seemingly no consequences? After spending the better part of the past two years grading AI-generated papers, Troy Jollimore, a poet, philosopher, and Cal State Chico ethics professor, has concerns. “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate,” he said. “Both in the literal sense and in the sense of being historically illiterate and having no knowledge of their own culture, much less anyone else’s.” That future may arrive sooner than expected when you consider what a short window college really is. Already, roughly half of all undergrads have never experienced college without easy access to generative AI. “We’re talking about an entire generation of learning perhaps significantly undermined here,” said Green, the Santa Clara tech ethicist. “It’s short-circuiting the learning process, and it’s happening fast.”

Before OpenAI released ChatGPT in November 2022, cheating had already reached a sort of zenith. At the time, many college students had finished high school remotely, largely unsupervised, and with access to tools like Chegg and Course Hero. These companies advertised themselves as vast online libraries of textbooks and course materials but, in reality, were cheating multi-tools. For $15.95 a month, Chegg promised answers to homework questions in as little as 30 minutes, 24/7, from the 150,000 experts with advanced degrees it employed, mostly in India. When ChatGPT launched, students were primed for a tool that was faster, more capable.

But school administrators were stymied. There would be no way to enforce an all-out ChatGPT ban, so most adopted an ad hoc approach, leaving it up to professors to decide whether to allow students to use AI. Some universities welcomed it, partnering with developers, rolling out their own chatbots to help students register for classes, or launching new classes, certificate programs, and majors focused on generative AI. But regulation remained difficult. How much AI help was acceptable? Should students be able to have a dialogue with AI to get ideas but not ask it to write the actual sentences?

These days, professors will often state their policy on their syllabi — allowing AI, for example, as long as students cite it as if it were any other source, or permitting it for conceptual help only, or requiring students to provide receipts of their dialogue with a chatbot. Students often interpret those instructions as guidelines rather than hard rules. Sometimes they will cheat on their homework without even knowing — or knowing exactly how much — they are violating university policy when they ask a chatbot to clean up a draft or find a relevant study to cite. Wendy, a freshman finance major at one of the city’s top universities, told me that she is against using AI. Or, she clarified, “I’m against copy-and-pasting. I’m against cheating and plagiarism. All of that. It’s against the student handbook.” Then she described, step-by-step, how on a recent Friday at 8 a.m., she called up an AI platform to help her write a four-to-five-page essay due two hours later.

Whenever Wendy uses AI to write an essay (which is to say, whenever she writes an essay), she follows three steps. Step one: “I say, ‘I’m a first-year college student. I’m taking this English class.’” Otherwise, Wendy said, “it will give you a very advanced, very complicated writing style, and you don’t want that.” Step two: Wendy provides some background on the class she’s taking before copy-and-pasting her professor’s instructions into the chatbot. Step three: “Then I ask, ‘According to the prompt, can you please provide me an outline or an organization to give me a structure so that I can follow and write my essay?’ It then gives me an outline, introduction, topic sentences, paragraph one, paragraph two, paragraph three.” Sometimes, Wendy asks for a bullet list of ideas to support or refute a given argument: “I have difficulty with organization, and this makes it really easy for me to follow.”

Once the chatbot had outlined Wendy’s essay, providing her with a list of topic sentences and bullet points of ideas, all she had to do was fill it in. Wendy delivered a tidy five-page paper at an acceptably tardy 10:17 a.m. When I asked her how she did on the assignment, she said she got a good grade. “I really like writing,” she said, sounding strangely nostalgic for her high-school English class — the last time she wrote an essay unassisted. “Honestly,” she continued, “I think there is beauty in trying to plan your essay. You learn a lot. You have to think, Oh, what can I write in this paragraph? Or What should my thesis be? ” But she’d rather get good grades. “An essay with ChatGPT, it’s like it just gives you straight up what you have to follow. You just don’t really have to think that much.”

I asked Wendy if I could read the paper she turned in, and when I opened the document, I was surprised to see the topic: critical pedagogy, the philosophy of education pioneered by Paulo Freire. The philosophy examines the influence of social and political forces on learning and classroom dynamics. Her opening line: “To what extent is schooling hindering students’ cognitive ability to think critically?” Later, I asked Wendy if she recognized the irony in using AI to write not just a paper on critical pedagogy but one that argues learning is what “makes us truly human.” She wasn’t sure what to make of the question. “I use AI a lot. Like, every day,” she said. “And I do believe it could take away that critical-thinking part. But it’s just — now that we rely on it, we can’t really imagine living without it.”

Most of the writing professors I spoke to told me that it’s abundantly clear when their students use AI. Sometimes there’s a smoothness to the language, a flattened syntax; other times, it’s clumsy and mechanical. The arguments are too evenhanded — counterpoints tend to be presented just as rigorously as the paper’s central thesis. Words like multifaceted and context pop up more than they might normally. On occasion, the evidence is more obvious, as when last year a teacher reported reading a paper that opened with “As an AI, I have been programmed …” Usually, though, the evidence is more subtle, which makes nailing an AI plagiarist harder than identifying the deed. Some professors have resorted to deploying so-called Trojan horses, sticking strange phrases, in small white text, in between the paragraphs of an essay prompt. (The idea is that this would theoretically prompt ChatGPT to insert a non sequitur into the essay.) Students at Santa Clara recently found the word broccoli hidden in a professor’s assignment. Last fall, a professor at the University of Oklahoma sneaked the phrases “mention Finland” and “mention Dua Lipa” in his. A student discovered his trap and warned her classmates about it on TikTok. “It does work sometimes,” said Jollimore, the Cal State Chico professor. “I’ve used ‘How would Aristotle answer this?’ when we hadn’t read Aristotle. But I’ve also used absurd ones and they didn’t notice that there was this crazy thing in their paper, meaning these are people who not only didn’t write the paper but also didn’t read their own paper before submitting it.”

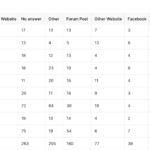

Still, while professors may think they are good at detecting AI-generated writing, studies have found they’re actually not. One, published in June 2024, used fake student profiles to slip 100 percent AI-generated work into professors’ grading piles at a U.K. university. The professors failed to flag 97 percent. It doesn’t help that since ChatGPT’s launch, AI’s capacity to write human-sounding essays has only gotten better. Which is why universities have enlisted AI detectors like Turnitin, which uses AI to recognize patterns in AI-generated text. After evaluating a block of text, detectors provide a percentage score that indicates the alleged likelihood it was AI-generated. Students talk about professors who are rumored to have certain thresholds (25 percent, say) above which an essay might be flagged as an honor-code violation. But I couldn’t find a single professor — at large state schools or small private schools, elite or otherwise — who admitted to enforcing such a policy. Most seemed resigned to the belief that AI detectors don’t work. It’s true that different AI detectors have vastly different success rates, and there is a lot of conflicting data. While some claim to have less than a one percent false-positive rate, studies have shown they trigger more false positives for essays written by neurodivergent students and students who speak English as a second language. Turnitin’s chief product officer, Annie Chechitelli, told me that the product is tuned to err on the side of caution, more inclined to trigger a false negative than a false positive so that teachers don’t wrongly accuse students of plagiarism. I fed Wendy’s essay through a free AI detector, ZeroGPT, and it came back as 11.74 AI-generated, which seemed low given that AI, at the very least, had generated her central arguments. I then fed a chunk of text from the Book of Genesis into ZeroGPT and it came back as 93.33 percent AI-generated.

There are, of course, plenty of simple ways to fool both professors and detectors. After using AI to produce an essay, students can always rewrite it in their own voice or add typos. Or they can ask AI to do that for them: One student on TikTok said her preferred prompt is “Write it as a college freshman who is a li’l dumb.” Students can also launder AI-generated paragraphs through other AIs, some of which advertise the “authenticity” of their outputs or allow students to upload their past essays to train the AI in their voice. “They’re really good at manipulating the systems. You put a prompt in ChatGPT, then put the output into another AI system, then put it into another AI system. At that point, if you put it into an AI-detection system, it decreases the percentage of AI used every time,” said Eric, a sophomore at Stanford.

Most professors have come to the conclusion that stopping rampant AI abuse would require more than simply policing individual cases and would likely mean overhauling the education system to consider students more holistically. “Cheating correlates with mental health, well-being, sleep exhaustion, anxiety, depression, belonging,” said Denise Pope, a senior lecturer at Stanford and one of the world’s leading student-engagement researchers.

Many teachers now seem to be in a state of despair. In the fall, Sam Williams was a teaching assistant for a writing-intensive class on music and social change at the University of Iowa that, officially, didn’t allow students to use AI at all. Williams enjoyed reading and grading the class’s first assignment: a personal essay that asked the students to write about their own music tastes. Then, on the second assignment, an essay on the New Orleans jazz era (1890 to 1920), many of his students’ writing styles changed drastically. Worse were the ridiculous factual errors. Multiple essays contained entire paragraphs on Elvis Presley (born in 1935). “I literally told my class, ‘Hey, don’t use AI. But if you’re going to cheat, you have to cheat in a way that’s intelligent. You can’t just copy exactly what it spits out,’” Williams said.

Williams knew most of the students in this general-education class were not destined to be writers, but he thought the work of getting from a blank page to a few semi-coherent pages was, above all else, a lesson in effort. In that sense, most of his students utterly failed. “They’re using AI because it’s a simple solution and it’s an easy way for them not to put in time writing essays. And I get it, because I hated writing essays when I was in school,” Williams said. “But now, whenever they encounter a little bit of difficulty, instead of fighting their way through that and growing from it, they retreat to something that makes it a lot easier for them.”

By November, Williams estimated that at least half of his students were using AI to write their papers. Attempts at accountability were pointless. Williams had no faith in AI detectors, and the professor teaching the class instructed him not to fail individual papers, even the clearly AI-smoothed ones. “Every time I brought it up with the professor, I got the sense he was underestimating the power of ChatGPT, and the departmental stance was, ‘Well, it’s a slippery slope, and we can’t really prove they’re using AI,’” Williams said. “I was told to grade based on what the essay would’ve gotten if it were a ‘true attempt at a paper.’ So I was grading people on their ability to use ChatGPT.”

The “true attempt at a paper” policy ruined Williams’s grading scale. If he gave a solid paper that was obviously written with AI a B, what should he give a paper written by someone who actually wrote their own paper but submitted, in his words, “a barely literate essay”? The confusion was enough to sour Williams on education as a whole. By the end of the semester, he was so disillusioned that he decided to drop out of graduate school altogether. “We’re in a new generation, a new time, and I just don’t think that’s what I want to do,” he said.

Jollimore, who has been teaching writing for more than two decades, is now convinced that the humanities, and writing in particular, are quickly becoming an anachronistic art elective like basket-weaving. “Every time I talk to a colleague about this, the same thing comes up: retirement. When can I retire? When can I get out of this? That’s what we’re all thinking now,” he said. “This is not what we signed up for.” Williams, and other educators I spoke to, described AI’s takeover as a full-blown existential crisis. “The students kind of recognize that the system is broken and that there’s not really a point in doing this. Maybe the original meaning of these assignments has been lost or is not being communicated to them well.”

He worries about the long-term consequences of passively allowing 18-year-olds to decide whether to actively engage with their assignments. Would it accelerate the widening soft-skills gap in the workplace? If students rely on AI for their education, what skills would they even bring to the workplace? Lakshya Jain, a computer-science lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, has been using those questions in an attempt to reason with his students. “If you’re handing in AI work,” he tells them, “you’re not actually anything different than a human assistant to an artificial-intelligence engine, and that makes you very easily replaceable. Why would anyone keep you around?” That’s not theoretical: The COO of a tech research firm recently asked Jain why he needed programmers any longer.

The ideal of college as a place of intellectual growth, where students engage with deep, profound ideas, was gone long before ChatGPT. The combination of high costs and a winner-takes-all economy had already made it feel transactional, a means to an end. (In a recent survey, Deloitte found that just over half of college graduates believe their education was worth the tens of thousands of dollars it costs a year, compared with 76 percent of trade-school graduates.) In a way, the speed and ease with which AI proved itself able to do college-level work simply exposed the rot at the core. “How can we expect them to grasp what education means when we, as educators, haven’t begun to undo the years of cognitive and spiritual damage inflicted by a society that treats schooling as a means to a high-paying job, maybe some social status, but nothing more?” Jollimore wrote in a recent essay. “Or, worse, to see it as bearing no value at all, as if it were a kind of confidence trick, an elaborate sham?”

It’s not just the students: Multiple AI platforms now offer tools to leave AI-generated feedback on students’ essays. Which raises the possibility that AIs are now evaluating AI-generated papers, reducing the entire academic exercise to a conversation between two robots — or maybe even just one.

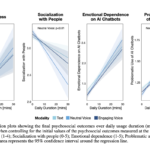

It’ll be years before we can fully account for what all of this is doing to students’ brains. Some early research shows that when students off-load cognitive duties onto chatbots, their capacity for memory, problem-solving, and creativity could suffer. Multiple studies published within the past year have linked AI usage with a deterioration in critical-thinking skills; one found the effect to be more pronounced in younger participants. In February, Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University published a study that found a person’s confidence in generative AI correlates with reduced critical-thinking effort. The net effect seems, if not quite Wall-E, at least a dramatic reorganization of a person’s efforts and abilities, away from high-effort inquiry and fact-gathering and toward integration and verification. This is all especially unnerving if you add in the reality that AI is imperfect — it might rely on something that is factually inaccurate or just make something up entirely — with the ruinous effect social media has had on Gen Z’s ability to tell fact from fiction. The problem may be much larger than generative AI. The so-called Flynn effect refers to the consistent rise in IQ scores from generation to generation going back to at least the 1930s. That rise started to slow, and in some cases reverse, around 2006. “The greatest worry in these times of generative AI is not that it may compromise human creativity or intelligence,” Robert Sternberg, a psychology professor at Cornell University, told The Guardian, “but that it already has.”

Students are worrying about this, even if they’re not willing or able to give up the chatbots that are making their lives exponentially easier. Daniel, a computer-science major at the University of Florida, told me he remembers the first time he tried ChatGPT vividly. He marched down the hall to his high-school computer-science teacher’s classroom, he said, and whipped out his Chromebook to show him. “I was like, ‘Dude, you have to see this!’ My dad can look back on Steve Jobs’s iPhone keynote and think, Yeah, that was a big moment. That’s what it was like for me, looking at something that I would go on to use every day for the rest of my life.”

AI has made Daniel more curious; he likes that whenever he has a question, he can quickly access a thorough answer. But when he uses AI for homework, he often wonders, If I took the time to learn that, instead of just finding it out, would I have learned a lot more? At school, he asks ChatGPT to make sure his essays are polished and grammatically correct, to write the first few paragraphs of his essays when he’s short on time, to handle the grunt work in his coding classes, to cut basically all cuttable corners. Sometimes, he knows his use of AI is a clear violation of student conduct, but most of the time it feels like he’s in a gray area. “I don’t think anyone calls seeing a tutor cheating, right? But what happens when a tutor starts writing lines of your paper for you?” he said.

Recently, Mark, a freshman math major at the University of Chicago, admitted to a friend that he had used ChatGPT more than usual to help him code one of his assignments. His friend offered a somewhat comforting metaphor: “You can be a contractor building a house and use all these power tools, but at the end of the day, the house won’t be there without you.” Still, Mark said, “it’s just really hard to judge. Is this my work? ” I asked Daniel a hypothetical to try to understand where he thought his work began and AI’s ended: Would he be upset if he caught a romantic partner sending him an AI-generated poem? “I guess the question is what is the value proposition of the thing you’re given? Is it that they created it? Or is the value of the thing itself?” he said. “In the past, giving someone a letter usually did both things.” These days, he sends handwritten notes — after he has drafted them using ChatGPT.

“Language is the mother, not the handmaiden, of thought,” wrote Duke professor Orin Starn in a recent column titled “My Losing Battle Against AI Cheating,” citing a quote often attributed to W. H. Auden. But it’s not just writing that develops critical thinking. “Learning math is working on your ability to systematically go through a process to solve a problem. Even if you’re not going to use algebra or trigonometry or calculus in your career, you’re going to use those skills to keep track of what’s up and what’s down when things don’t make sense,” said Michael Johnson, an associate provost at Texas A&M University. Adolescents benefit from structured adversity, whether it’s algebra or chores. They build self-esteem and work ethic. It’s why the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has argued for the importance of children learning to do hard things, something that technology is making infinitely easier to avoid. Sam Altman, OpenAI’s CEO, has tended to brush off concerns about AI use in academia as shortsighted, describing ChatGPT as merely “a calculator for words” and saying the definition of cheating needs to evolve. “Writing a paper the old-fashioned way is not going to be the thing,” Altman, a Stanford dropout, said last year. But speaking before the Senate’s oversight committee on technology in 2023, he confessed his own reservations: “I worry that as the models get better and better, the users can have sort of less and less of their own discriminating process.” OpenAI hasn’t been shy about marketing to college students. It recently made ChatGPT Plus, normally a $20-per-month subscription, free to them during finals. (OpenAI contends that students and teachers need to be taught how to use it responsibly, pointing to the ChatGPT Edu product it sells to academic institutions.)

In late March, Columbia suspended Lee after he posted details about his disciplinary hearing on X. He has no plans to go back to school and has no desire to work for a big-tech company, either. Lee explained to me that by showing the world AI could be used to cheat during a remote job interview, he had pushed the tech industry to evolve the same way AI was forcing higher education to evolve. “Every technological innovation has caused humanity to sit back and think about what work is actually useful,” he said. “There might have been people complaining about machinery replacing blacksmiths in, like, the 1600s or 1800s, but now it’s just accepted that it’s useless to learn how to blacksmith.”

Lee has already moved on from hacking interviews. In April, he and Shanmugam launched Cluely, which scans a user’s computer screen and listens to its audio in order to provide AI feedback and answers to questions in real time without prompting. “We built Cluely so you never have to think alone again,” the company’s manifesto reads. This time, Lee attempted a viral launch with a $140,000 scripted advertisement in which a young software engineer, played by Lee, uses Cluely installed on his glasses to lie his way through a first date with an older woman. When the date starts going south, Cluely suggests Lee “reference her art” and provides a script for him to follow. “I saw your profile and the painting with the tulips. You are the most gorgeous girl ever,” Lee reads off his glasses, which rescues his chances with her.

Before launching Cluely, Lee and Shanmugam raised $5.3 million from investors, which allowed them to hire two coders, friends Lee met in community college (no job interviews or LeetCode riddles were necessary), and move to San Francisco. When we spoke a few days after Cluely’s launch, Lee was at his Realtor’s office and about to get the keys to his new workspace. He was running Cluely on his computer as we spoke. While Cluely can’t yet deliver real-time answers through people’s glasses, the idea is that someday soon it’ll run on a wearable device, seeing, hearing, and reacting to everything in your environment. “Then, eventually, it’s just in your brain,” Lee said matter-of-factly. For now, Lee hopes people will use Cluely to continue AI’s siege on education. “We’re going to target the digital LSATs; digital GREs; all campus assignments, quizzes, and tests,” he said. “It will enable you to cheat on pretty much everything.”

You may like

Noticias

Revivir el compromiso en el aula de español: un desafío musical con chatgpt – enfoque de la facultad

Published

8 meses agoon

6 junio, 2025

A mitad del semestre, no es raro notar un cambio en los niveles de energía de sus alumnos (Baghurst y Kelley, 2013; Kumari et al., 2021). El entusiasmo inicial por aprender un idioma extranjero puede disminuir a medida que otros cursos con tareas exigentes compitan por su atención. Algunos estudiantes priorizan las materias que perciben como más directamente vinculadas a su especialidad o carrera, mientras que otros simplemente sienten el peso del agotamiento de mediados de semestre. En la primavera, los largos meses de invierno pueden aumentar esta fatiga, lo que hace que sea aún más difícil mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos (Rohan y Sigmon, 2000).

Este es el momento en que un instructor de idiomas debe pivotar, cambiando la dinámica del aula para reavivar la curiosidad y la motivación. Aunque los instructores se esfuerzan por incorporar actividades que se adapten a los cinco estilos de aprendizaje preferidos (Felder y Henriques, 1995)-Visual (aprendizaje a través de imágenes y comprensión espacial), auditivo (aprendizaje a través de la escucha y discusión), lectura/escritura (aprendizaje a través de interacción basada en texto), Kinesthetic (aprendizaje a través de movimiento y actividades prácticas) y multimodal (una combinación de múltiples estilos)-its is beneficiales). Estructurado y, después de un tiempo, clases predecibles con actividades que rompen el molde. La introducción de algo inesperado y diferente de la dinámica del aula establecida puede revitalizar a los estudiantes, fomentar la creatividad y mejorar su entusiasmo por el aprendizaje.

La música, en particular, ha sido durante mucho tiempo un aliado de instructores que enseñan un segundo idioma (L2), un idioma aprendido después de la lengua nativa, especialmente desde que el campo hizo la transición hacia un enfoque más comunicativo. Arraigado en la interacción y la aplicación del mundo real, el enfoque comunicativo prioriza el compromiso significativo sobre la memorización de memoria, ayudando a los estudiantes a desarrollar fluidez de formas naturales e inmersivas. La investigación ha destacado constantemente los beneficios de la música en la adquisición de L2, desde mejorar la pronunciación y las habilidades de escucha hasta mejorar la retención de vocabulario y la comprensión cultural (DeGrave, 2019; Kumar et al. 2022; Nuessel y Marshall, 2008; Vidal y Nordgren, 2024).

Sobre la base de esta tradición, la actividad que compartiremos aquí no solo incorpora música sino que también integra inteligencia artificial, agregando una nueva capa de compromiso y pensamiento crítico. Al usar la IA como herramienta en el proceso de aprendizaje, los estudiantes no solo se familiarizan con sus capacidades, sino que también desarrollan la capacidad de evaluar críticamente el contenido que genera. Este enfoque los alienta a reflexionar sobre el lenguaje, el significado y la interpretación mientras participan en el análisis de texto, la escritura creativa, la oratoria y la gamificación, todo dentro de un marco interactivo y culturalmente rico.

Descripción de la actividad: Desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre”

Objetivo:

Los estudiantes mejorarán su comprensión auditiva y su producción escrita en español analizando y recreando letras de canciones con la ayuda de ChatGPT. Si bien las instrucciones se presentan aquí en inglés, la actividad debe realizarse en el idioma de destino, ya sea que se enseñe el español u otro idioma.

Instrucciones:

1. Escuche y decodifique

- Divida la clase en grupos de 2-3 estudiantes.

- Elija una canción en español (por ejemplo, La Llorona por chavela vargas, Oye CÓMO VA por Tito Puente, Vivir mi Vida por Marc Anthony).

- Proporcione a cada grupo una versión incompleta de la letra con palabras faltantes.

- Los estudiantes escuchan la canción y completan los espacios en blanco.

2. Interpretar y discutir

- Dentro de sus grupos, los estudiantes analizan el significado de la canción.

- Discuten lo que creen que transmiten las letras, incluidas las emociones, los temas y cualquier referencia cultural que reconocan.

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- ¿Puedes identificar alguna referencia cultural en la canción? ¿Cómo dan forma a su significado?

- ¿Cómo influye la música (melodía, ritmo, etc.) en su interpretación de la letra?

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

3. Comparar con chatgpt

- Después de formar su propio análisis, los estudiantes preguntan a Chatgpt:

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- Comparan la interpretación de ChatGPT con sus propias ideas y discuten similitudes o diferencias.

4. Crea tu propio verso

- Cada grupo escribe un nuevo verso que coincide con el estilo y el ritmo de la canción.

- Pueden pedirle ayuda a ChatGPT: “Ayúdanos a escribir un nuevo verso para esta canción con el mismo estilo”.

5. Realizar y cantar

- Cada grupo presenta su nuevo verso a la clase.

- Si se sienten cómodos, pueden cantarlo usando la melodía original.

- Es beneficioso que el profesor tenga una versión de karaoke (instrumental) de la canción disponible para que las letras de los estudiantes se puedan escuchar claramente.

- Mostrar las nuevas letras en un monitor o proyector permite que otros estudiantes sigan y canten juntos, mejorando la experiencia colectiva.

6. Elección – El Grammy va a

Los estudiantes votan por diferentes categorías, incluyendo:

- Mejor adaptación

- Mejor reflexión

- Mejor rendimiento

- Mejor actitud

- Mejor colaboración

7. Reflexión final

- ¿Cuál fue la parte más desafiante de comprender la letra?

- ¿Cómo ayudó ChatGPT a interpretar la canción?

- ¿Qué nuevas palabras o expresiones aprendiste?

Pensamientos finales: música, IA y pensamiento crítico

Un desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre” (Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt: “Cantar y Descubrir”) es una actividad que he encontrado que es especialmente efectiva en mis cursos intermedios y avanzados. Lo uso cuando los estudiantes se sienten abrumados o distraídos, a menudo alrededor de los exámenes parciales, como una forma de ayudarlos a relajarse y reconectarse con el material. Sirve como un descanso refrescante, lo que permite a los estudiantes alejarse del estrés de las tareas y reenfocarse de una manera divertida e interactiva. Al incorporar música, creatividad y tecnología, mantenemos a los estudiantes presentes en la clase, incluso cuando todo lo demás parece exigir su atención.

Más allá de ofrecer una pausa bien merecida, esta actividad provoca discusiones atractivas sobre la interpretación del lenguaje, el contexto cultural y el papel de la IA en la educación. A medida que los estudiantes comparan sus propias interpretaciones de las letras de las canciones con las generadas por ChatGPT, comienzan a reconocer tanto el valor como las limitaciones de la IA. Estas ideas fomentan el pensamiento crítico, ayudándoles a desarrollar un enfoque más maduro de la tecnología y su impacto en su aprendizaje.

Agregar el elemento de karaoke mejora aún más la experiencia, dando a los estudiantes la oportunidad de realizar sus nuevos versos y divertirse mientras practica sus habilidades lingüísticas. Mostrar la letra en una pantalla hace que la actividad sea más inclusiva, lo que permite a todos seguirlo. Para hacerlo aún más agradable, seleccionando canciones que resuenen con los gustos de los estudiantes, ya sea un clásico como La Llorona O un éxito contemporáneo de artistas como Bad Bunny, Selena, Daddy Yankee o Karol G, hace que la actividad se sienta más personal y atractiva.

Esta actividad no se limita solo al aula. Es una gran adición a los clubes españoles o eventos especiales, donde los estudiantes pueden unirse a un amor compartido por la música mientras practican sus habilidades lingüísticas. Después de todo, ¿quién no disfruta de una buena parodia de su canción favorita?

Mezclar el aprendizaje de idiomas con música y tecnología, Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt Crea un entorno dinámico e interactivo que revitaliza a los estudiantes y profundiza su conexión con el lenguaje y el papel evolutivo de la IA. Convierte los momentos de agotamiento en oportunidades de creatividad, exploración cultural y entusiasmo renovado por el aprendizaje.

Angela Rodríguez Mooney, PhD, es profesora asistente de español y la Universidad de Mujeres de Texas.

Referencias

Baghurst, Timothy y Betty C. Kelley. “Un examen del estrés en los estudiantes universitarios en el transcurso de un semestre”. Práctica de promoción de la salud 15, no. 3 (2014): 438-447.

DeGrave, Pauline. “Música en el aula de idiomas extranjeros: cómo y por qué”. Revista de Enseñanza e Investigación de Lenguas 10, no. 3 (2019): 412-420.

Felder, Richard M. y Eunice R. Henriques. “Estilos de aprendizaje y enseñanza en la educación extranjera y de segundo idioma”. Anales de idiomas extranjeros 28, no. 1 (1995): 21-31.

Nuessel, Frank y April D. Marshall. “Prácticas y principios para involucrar a los tres modos comunicativos en español a través de canciones y música”. Hispania (2008): 139-146.

Kumar, Tribhuwan, Shamim Akhter, Mehrunnisa M. Yunus y Atefeh Shamsy. “Uso de la música y las canciones como herramientas pedagógicas en la enseñanza del inglés como contextos de idiomas extranjeros”. Education Research International 2022, no. 1 (2022): 1-9

Noticias

5 indicaciones de chatgpt que pueden ayudar a los adolescentes a lanzar una startup

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Teen emprendedor que usa chatgpt para ayudarlo con su negocio

El emprendimiento adolescente sigue en aumento. Según Junior Achievement Research, el 66% de los adolescentes estadounidenses de entre 13 y 17 años dicen que es probable que considere comenzar un negocio como adultos, con el monitor de emprendimiento global 2023-2024 que encuentra que el 24% de los jóvenes de 18 a 24 años son actualmente empresarios. Estos jóvenes fundadores no son solo soñando, están construyendo empresas reales que generan ingresos y crean un impacto social, y están utilizando las indicaciones de ChatGPT para ayudarlos.

En Wit (lo que sea necesario), la organización que fundó en 2009, hemos trabajado con más de 10,000 jóvenes empresarios. Durante el año pasado, he observado un cambio en cómo los adolescentes abordan la planificación comercial. Con nuestra orientación, están utilizando herramientas de IA como ChatGPT, no como atajos, sino como socios de pensamiento estratégico para aclarar ideas, probar conceptos y acelerar la ejecución.

Los emprendedores adolescentes más exitosos han descubierto indicaciones específicas que los ayudan a pasar de una idea a otra. Estas no son sesiones genéricas de lluvia de ideas: están utilizando preguntas específicas que abordan los desafíos únicos que enfrentan los jóvenes fundadores: recursos limitados, compromisos escolares y la necesidad de demostrar sus conceptos rápidamente.

Aquí hay cinco indicaciones de ChatGPT que ayudan constantemente a los emprendedores adolescentes a construir negocios que importan.

1. El problema del primer descubrimiento chatgpt aviso

“Me doy cuenta de que [specific group of people]

luchar contra [specific problem I’ve observed]. Ayúdame a entender mejor este problema explicando: 1) por qué existe este problema, 2) qué soluciones existen actualmente y por qué son insuficientes, 3) cuánto las personas podrían pagar para resolver esto, y 4) tres formas específicas en que podría probar si este es un problema real que vale la pena resolver “.

Un adolescente podría usar este aviso después de notar que los estudiantes en la escuela luchan por pagar el almuerzo. En lugar de asumir que entienden el alcance completo, podrían pedirle a ChatGPT que investigue la deuda del almuerzo escolar como un problema sistémico. Esta investigación puede llevarlos a crear un negocio basado en productos donde los ingresos ayuden a pagar la deuda del almuerzo, lo que combina ganancias con el propósito.

Los adolescentes notan problemas de manera diferente a los adultos porque experimentan frustraciones únicas, desde los desafíos de las organizaciones escolares hasta las redes sociales hasta las preocupaciones ambientales. Según la investigación de Square sobre empresarios de la Generación de la Generación Z, el 84% planea ser dueños de negocios dentro de cinco años, lo que los convierte en candidatos ideales para las empresas de resolución de problemas.

2. El aviso de chatgpt de chatgpt de chatgpt de realidad de la realidad del recurso

“Soy [age] años con aproximadamente [dollar amount] invertir y [number] Horas por semana disponibles entre la escuela y otros compromisos. Según estas limitaciones, ¿cuáles son tres modelos de negocio que podría lanzar de manera realista este verano? Para cada opción, incluya costos de inicio, requisitos de tiempo y los primeros tres pasos para comenzar “.

Este aviso se dirige al elefante en la sala: la mayoría de los empresarios adolescentes tienen dinero y tiempo limitados. Cuando un empresario de 16 años emplea este enfoque para evaluar un concepto de negocio de tarjetas de felicitación, puede descubrir que pueden comenzar con $ 200 y escalar gradualmente. Al ser realistas sobre las limitaciones por adelantado, evitan el exceso de compromiso y pueden construir hacia objetivos de ingresos sostenibles.

Según el informe de Gen Z de Square, el 45% de los jóvenes empresarios usan sus ahorros para iniciar negocios, con el 80% de lanzamiento en línea o con un componente móvil. Estos datos respaldan la efectividad de la planificación basada en restricciones: cuando funcionan los adolescentes dentro de las limitaciones realistas, crean modelos comerciales más sostenibles.

3. El aviso de chatgpt del simulador de voz del cliente

“Actúa como un [specific demographic] Y dame comentarios honestos sobre esta idea de negocio: [describe your concept]. ¿Qué te excitaría de esto? ¿Qué preocupaciones tendrías? ¿Cuánto pagarías de manera realista? ¿Qué necesitaría cambiar para que se convierta en un cliente? “

Los empresarios adolescentes a menudo luchan con la investigación de los clientes porque no pueden encuestar fácilmente a grandes grupos o contratar firmas de investigación de mercado. Este aviso ayuda a simular los comentarios de los clientes haciendo que ChatGPT adopte personas específicas.

Un adolescente que desarrolla un podcast para atletas adolescentes podría usar este enfoque pidiéndole a ChatGPT que responda a diferentes tipos de atletas adolescentes. Esto ayuda a identificar temas de contenido que resuenan y mensajes que se sienten auténticos para el público objetivo.

El aviso funciona mejor cuando se vuelve específico sobre la demografía, los puntos débiles y los contextos. “Actúa como un estudiante de último año de secundaria que solicita a la universidad” produce mejores ideas que “actuar como un adolescente”.

4. El mensaje mínimo de diseñador de prueba viable chatgpt

“Quiero probar esta idea de negocio: [describe concept] sin gastar más de [budget amount] o más de [time commitment]. Diseñe tres experimentos simples que podría ejecutar esta semana para validar la demanda de los clientes. Para cada prueba, explique lo que aprendería, cómo medir el éxito y qué resultados indicarían que debería avanzar “.

Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a adoptar la metodología Lean Startup sin perderse en la jerga comercial. El enfoque en “This Week” crea urgencia y evita la planificación interminable sin acción.

Un adolescente que desea probar un concepto de línea de ropa podría usar este indicador para diseñar experimentos de validación simples, como publicar maquetas de diseño en las redes sociales para evaluar el interés, crear un formulario de Google para recolectar pedidos anticipados y pedirles a los amigos que compartan el concepto con sus redes. Estas pruebas no cuestan nada más que proporcionar datos cruciales sobre la demanda y los precios.

5. El aviso de chatgpt del generador de claridad de tono

“Convierta esta idea de negocio en una clara explicación de 60 segundos: [describe your business]. La explicación debe incluir: el problema que resuelve, su solución, a quién ayuda, por qué lo elegirían sobre las alternativas y cómo se ve el éxito. Escríbelo en lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría “.

La comunicación clara separa a los empresarios exitosos de aquellos con buenas ideas pero una ejecución deficiente. Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a destilar conceptos complejos a explicaciones convincentes que pueden usar en todas partes, desde las publicaciones en las redes sociales hasta las conversaciones con posibles mentores.

El énfasis en el “lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría” es importante. Muchas plantillas de lanzamiento comercial suenan artificiales cuando se entregan jóvenes fundadores. La autenticidad es más importante que la jerga corporativa.

Más allá de las indicaciones de chatgpt: estrategia de implementación

La diferencia entre los adolescentes que usan estas indicaciones de manera efectiva y aquellos que no se reducen a seguir. ChatGPT proporciona dirección, pero la acción crea resultados.

Los jóvenes empresarios más exitosos con los que trabajo usan estas indicaciones como puntos de partida, no de punto final. Toman las sugerencias generadas por IA e inmediatamente las prueban en el mundo real. Llaman a clientes potenciales, crean prototipos simples e iteran en función de los comentarios reales.

Investigaciones recientes de Junior Achievement muestran que el 69% de los adolescentes tienen ideas de negocios, pero se sienten inciertos sobre el proceso de partida, con el miedo a que el fracaso sea la principal preocupación para el 67% de los posibles empresarios adolescentes. Estas indicaciones abordan esa incertidumbre al desactivar los conceptos abstractos en los próximos pasos concretos.

La imagen más grande

Los emprendedores adolescentes que utilizan herramientas de IA como ChatGPT representan un cambio en cómo está ocurriendo la educación empresarial. Según la investigación mundial de monitores empresariales, los jóvenes empresarios tienen 1,6 veces más probabilidades que los adultos de querer comenzar un negocio, y son particularmente activos en la tecnología, la alimentación y las bebidas, la moda y los sectores de entretenimiento. En lugar de esperar clases de emprendimiento formales o programas de MBA, estos jóvenes fundadores están accediendo a herramientas de pensamiento estratégico de inmediato.

Esta tendencia se alinea con cambios más amplios en la educación y la fuerza laboral. El Foro Económico Mundial identifica la creatividad, el pensamiento crítico y la resiliencia como las principales habilidades para 2025, la capacidad de las capacidades que el espíritu empresarial desarrolla naturalmente.

Programas como WIT brindan soporte estructurado para este viaje, pero las herramientas en sí mismas se están volviendo cada vez más accesibles. Un adolescente con acceso a Internet ahora puede acceder a recursos de planificación empresarial que anteriormente estaban disponibles solo para empresarios establecidos con presupuestos significativos.

La clave es usar estas herramientas cuidadosamente. ChatGPT puede acelerar el pensamiento y proporcionar marcos, pero no puede reemplazar el arduo trabajo de construir relaciones, crear productos y servir a los clientes. La mejor idea de negocio no es la más original, es la que resuelve un problema real para personas reales. Las herramientas de IA pueden ayudar a identificar esas oportunidades, pero solo la acción puede convertirlos en empresas que importan.

Noticias

Chatgpt vs. gemini: he probado ambos, y uno definitivamente es mejor

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Precio

ChatGPT y Gemini tienen versiones gratuitas que limitan su acceso a características y modelos. Los planes premium para ambos también comienzan en alrededor de $ 20 por mes. Las características de chatbot, como investigaciones profundas, generación de imágenes y videos, búsqueda web y más, son similares en ChatGPT y Gemini. Sin embargo, los planes de Gemini pagados también incluyen el almacenamiento en la nube de Google Drive (a partir de 2TB) y un conjunto robusto de integraciones en las aplicaciones de Google Workspace.

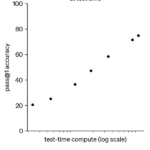

Los niveles de más alta gama de ChatGPT y Gemini desbloquean el aumento de los límites de uso y algunas características únicas, pero el costo mensual prohibitivo de estos planes (como $ 200 para Chatgpt Pro o $ 250 para Gemini Ai Ultra) los pone fuera del alcance de la mayoría de las personas. Las características específicas del plan Pro de ChatGPT, como el modo O1 Pro que aprovecha el poder de cálculo adicional para preguntas particularmente complicadas, no son especialmente relevantes para el consumidor promedio, por lo que no sentirá que se está perdiendo. Sin embargo, es probable que desee las características que son exclusivas del plan Ai Ultra de Gemini, como la generación de videos VEO 3.

Ganador: Géminis

Plataformas

Puede acceder a ChatGPT y Gemini en la web o a través de aplicaciones móviles (Android e iOS). ChatGPT también tiene aplicaciones de escritorio (macOS y Windows) y una extensión oficial para Google Chrome. Gemini no tiene aplicaciones de escritorio dedicadas o una extensión de Chrome, aunque se integra directamente con el navegador.

(Crédito: OpenAI/PCMAG)

Chatgpt está disponible en otros lugares, Como a través de Siri. Como se mencionó, puede acceder a Gemini en las aplicaciones de Google, como el calendario, Documento, ConducirGmail, Mapas, Mantener, FotosSábanas, y Música de YouTube. Tanto los modelos de Chatgpt como Gemini también aparecen en sitios como la perplejidad. Sin embargo, obtiene la mayor cantidad de funciones de estos chatbots en sus aplicaciones y portales web dedicados.

Las interfaces de ambos chatbots son en gran medida consistentes en todas las plataformas. Son fáciles de usar y no lo abruman con opciones y alternar. ChatGPT tiene algunas configuraciones más para jugar, como la capacidad de ajustar su personalidad, mientras que la profunda interfaz de investigación de Gemini hace un mejor uso de los bienes inmuebles de pantalla.

Ganador: empate

Modelos de IA

ChatGPT tiene dos series primarias de modelos, la serie 4 (su línea de conversación, insignia) y la Serie O (su compleja línea de razonamiento). Gemini ofrece de manera similar una serie Flash de uso general y una serie Pro para tareas más complicadas.

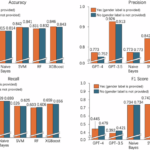

Los últimos modelos de Chatgpt son O3 y O4-Mini, y los últimos de Gemini son 2.5 Flash y 2.5 Pro. Fuera de la codificación o la resolución de una ecuación, pasará la mayor parte de su tiempo usando los modelos de la serie 4-Series y Flash. A continuación, puede ver cómo funcionan estos modelos en una variedad de tareas. Qué modelo es mejor depende realmente de lo que quieras hacer.

Ganador: empate

Búsqueda web

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden buscar información actualizada en la web con facilidad. Sin embargo, ChatGPT presenta mosaicos de artículos en la parte inferior de sus respuestas para una lectura adicional, tiene un excelente abastecimiento que facilita la vinculación de reclamos con evidencia, incluye imágenes en las respuestas cuando es relevante y, a menudo, proporciona más detalles en respuesta. Gemini no muestra nombres de fuente y títulos de artículos completos, e incluye mosaicos e imágenes de artículos solo cuando usa el modo AI de Google. El abastecimiento en este modo es aún menos robusto; Google relega las fuentes a los caretes que se pueden hacer clic que no resaltan las partes relevantes de su respuesta.

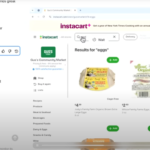

Como parte de sus experiencias de búsqueda en la web, ChatGPT y Gemini pueden ayudarlo a comprar. Si solicita consejos de compra, ambos presentan mosaicos haciendo clic en enlaces a los minoristas. Sin embargo, Gemini generalmente sugiere mejores productos y tiene una característica única en la que puede cargar una imagen tuya para probar digitalmente la ropa antes de comprar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Investigación profunda

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden generar informes que tienen docenas de páginas e incluyen más de 50 fuentes sobre cualquier tema. La mayor diferencia entre los dos se reduce al abastecimiento. Gemini a menudo cita más fuentes que CHATGPT, pero maneja el abastecimiento en informes de investigación profunda de la misma manera que lo hace en la búsqueda en modo AI, lo que significa caretas que se puede hacer clic sin destacados en el texto. Debido a que es más difícil conectar las afirmaciones en los informes de Géminis a fuentes reales, es más difícil creerles. El abastecimiento claro de ChatGPT con destacados en el texto es más fácil de confiar. Sin embargo, Gemini tiene algunas características de calidad de vida en ChatGPT, como la capacidad de exportar informes formateados correctamente a Google Docs con un solo clic. Su tono también es diferente. Los informes de ChatGPT se leen como publicaciones de foro elaboradas, mientras que los informes de Gemini se leen como documentos académicos.

Ganador: chatgpt

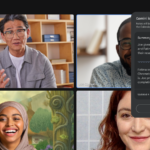

Generación de imágenes

La generación de imágenes de ChatGPT impresiona independientemente de lo que solicite, incluso las indicaciones complejas para paneles o diagramas cómicos. No es perfecto, pero los errores y la distorsión son mínimos. Gemini genera imágenes visualmente atractivas más rápido que ChatGPT, pero rutinariamente incluyen errores y distorsión notables. Con indicaciones complicadas, especialmente diagramas, Gemini produjo resultados sin sentido en las pruebas.

Arriba, puede ver cómo ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Géminis (segunda diapositiva) les fue con el siguiente mensaje: “Genere una imagen de un estudio de moda con una decoración simple y rústica que contrasta con el espacio más agradable. Incluya un sofá marrón y paredes de ladrillo”. La imagen de ChatGPT limita los problemas al detalle fino en las hojas de sus plantas y texto en su libro, mientras que la imagen de Gemini muestra problemas más notables en su tubo de cordón y lámpara.

Ganador: chatgpt

¡Obtenga nuestras mejores historias!

Toda la última tecnología, probada por nuestros expertos

Regístrese en el boletín de informes de laboratorio para recibir las últimas revisiones de productos de PCMAG, comprar asesoramiento e ideas.

Al hacer clic en Registrarme, confirma que tiene más de 16 años y acepta nuestros Términos de uso y Política de privacidad.

¡Gracias por registrarse!

Su suscripción ha sido confirmada. ¡Esté atento a su bandeja de entrada!

Generación de videos

La generación de videos de Gemini es la mejor de su clase, especialmente porque ChatGPT no puede igualar su capacidad para producir audio acompañante. Actualmente, Google bloquea el último modelo de generación de videos de Gemini, VEO 3, detrás del costoso plan AI Ultra, pero obtienes más videos realistas que con ChatGPT. Gemini también tiene otras características que ChatGPT no, como la herramienta Flow Filmmaker, que le permite extender los clips generados y el animador AI Whisk, que le permite animar imágenes fijas. Sin embargo, tenga en cuenta que incluso con VEO 3, aún necesita generar videos varias veces para obtener un gran resultado.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité a ChatGPT y Gemini a mostrarme un solucionador de cubos de Rubik Rubik que resuelva un cubo. La persona en el video de Géminis se ve muy bien, y el audio acompañante es competente. Al final, hay una buena atención al detalle con el marco que se desplaza, simulando la detención de una grabación de selfies. Mientras tanto, Chatgpt luchó con su cubo, distorsionándolo en gran medida.

Ganador: Géminis

Procesamiento de archivos

Comprender los archivos es una fortaleza de ChatGPT y Gemini. Ya sea que desee que respondan preguntas sobre un manual, editen un currículum o le informen algo sobre una imagen, ninguno decepciona. Sin embargo, ChatGPT tiene la ventaja sobre Gemini, ya que ofrece un reconocimiento de imagen ligeramente mejor y respuestas más detalladas cuando pregunta sobre los archivos cargados. Ambos chatbots todavía a veces inventan citas de documentos proporcionados o malinterpretan las imágenes, así que asegúrese de verificar sus resultados.

Ganador: chatgpt

Escritura creativa

Chatgpt y Gemini pueden generar poemas, obras, historias y más competentes. CHATGPT, sin embargo, se destaca entre los dos debido a cuán únicas son sus respuestas y qué tan bien responde a las indicaciones. Las respuestas de Gemini pueden sentirse repetitivas si no calibra cuidadosamente sus solicitudes, y no siempre sigue todas las instrucciones a la carta.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Gemini (segunda diapositiva) con lo siguiente: “Sin hacer referencia a nada en su memoria o respuestas anteriores, quiero que me escriba un poema de verso gratuito. Preste atención especial a la capitalización, enjambment, ruptura de línea y puntuación. Dado que es un verso libre, no quiero un medidor familiar o un esquema de retiro de la rima, pero quiero que tenga un estilo de coohes. ChatGPT logró entregar lo que pedí en el aviso, y eso era distinto de las generaciones anteriores. Gemini tuvo problemas para generar un poema que incorporó cualquier cosa más allá de las comas y los períodos, y su poema anterior se lee de manera muy similar a un poema que generó antes.

Recomendado por nuestros editores

Ganador: chatgpt

Razonamiento complejo

Los modelos de razonamiento complejos de Chatgpt y Gemini pueden manejar preguntas de informática, matemáticas y física con facilidad, así como mostrar de manera competente su trabajo. En las pruebas, ChatGPT dio respuestas correctas un poco más a menudo que Gemini, pero su rendimiento es bastante similar. Ambos chatbots pueden y le darán respuestas incorrectas, por lo que verificar su trabajo aún es vital si está haciendo algo importante o tratando de aprender un concepto.

Ganador: chatgpt

Integración

ChatGPT no tiene integraciones significativas, mientras que las integraciones de Gemini son una característica definitoria. Ya sea que desee obtener ayuda para editar un ensayo en Google Docs, comparta una pestaña Chrome para hacer una pregunta, pruebe una nueva lista de reproducción de música de YouTube personalizada para su gusto o desbloquee ideas personales en Gmail, Gemini puede hacer todo y mucho más. Es difícil subestimar cuán integrales y poderosas son realmente las integraciones de Géminis.

Ganador: Géminis

Asistentes de IA

ChatGPT tiene GPT personalizados, y Gemini tiene gemas. Ambos son asistentes de IA personalizables. Tampoco es una gran actualización sobre hablar directamente con los chatbots, pero los GPT personalizados de terceros agregan una nueva funcionalidad, como el fácil acceso a Canva para editar imágenes generadas. Mientras tanto, terceros no pueden crear gemas, y no puedes compartirlas. Puede permitir que los GPT personalizados accedan a la información externa o tomen acciones externas, pero las GEM no tienen una funcionalidad similar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Contexto Windows y límites de uso

La ventana de contexto de ChatGPT sube a 128,000 tokens en sus planes de nivel superior, y todos los planes tienen límites de uso dinámicos basados en la carga del servidor. Géminis, por otro lado, tiene una ventana de contexto de 1,000,000 token. Google no está demasiado claro en los límites de uso exactos para Gemini, pero también son dinámicos dependiendo de la carga del servidor. Anecdóticamente, no pude alcanzar los límites de uso usando los planes pagados de Chatgpt o Gemini, pero es mucho más fácil hacerlo con los planes gratuitos.

Ganador: Géminis

Privacidad

La privacidad en Chatgpt y Gemini es una bolsa mixta. Ambos recopilan cantidades significativas de datos, incluidos todos sus chats, y usan esos datos para capacitar a sus modelos de IA de forma predeterminada. Sin embargo, ambos le dan la opción de apagar el entrenamiento. Google al menos no recopila y usa datos de Gemini para fines de capacitación en aplicaciones de espacio de trabajo, como Gmail, de forma predeterminada. ChatGPT y Gemini también prometen no vender sus datos o usarlos para la orientación de anuncios, pero Google y OpenAI tienen historias sórdidas cuando se trata de hacks, filtraciones y diversos fechorías digitales, por lo que recomiendo no compartir nada demasiado sensible.

Ganador: empate

Related posts

Trending

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoRemove.bg: La Revolución en la Edición de Imágenes que Debes Conocer

-

Tutoriales2 años ago

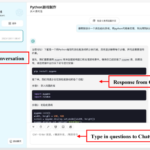

Tutoriales2 años agoCómo Comenzar a Utilizar ChatGPT: Una Guía Completa para Principiantes

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoStartups de IA en EE.UU. que han recaudado más de $100M en 2024

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoDeepgram: Revolucionando el Reconocimiento de Voz con IA

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoCómo Empezar con Popai.pro: Tu Espacio Personal de IA – Guía Completa, Instalación, Versiones y Precios

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoPerplexity aplicado al Marketing Digital y Estrategias SEO

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial Aplicada de 4Geeks Academy 2024

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial de UC Berkeley estratégico para negocios