Noticias

Artificial intelligence may affect diversity: architecture and cultural context reflected through ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Google Maps

Published

4 meses agoon

Adobor H (2021) Open strategy: what is the impact of national culture? Manag Res Rev. 44:1277–1297. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-06-2020-0334

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Airoldi M, Rokka J (2022) Algorithmic consumer culture. Consum Mark. Cult. 25:411–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2022.2084726

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Ali T, Marc B, Omar B et al. (2021) Exploring destination’s negative e-reputation using aspect-based sentiment analysis approach: case of Marrakech destination on TripAdvisor. Tour. Manag Perspect. 40:100892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100892

Article

Google Scholar

Andersson R, Bråmå Å (2018) The Stockholm estates: a tale of the importance of initial conditions, macroeconomic dependencies, tenure and immigration. In: Hess D, Tammaru T, van Ham M (eds.) Housing estates in Europe, 1st edn. Springer, Cham, p 361–388

Anon (2023) How to worry wisely about artificial intelligence. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/04/20/how-to-worry-wisely-about-artificial-intelligence

Berman A, de Fine Licht K, Carlsson V (2024) Trustworthy AI in the public sector: an empirical analysis of a Swedish labor market decision-support system. Technol. Soc. 76:102471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102471

Article

Google Scholar

Bircan T, Korkmaz EE (2021) Big data for whose sake? Governing migration through artificial intelligence. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00910-x

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Borbáth E, Hutter S, Leininger A (2023) Cleavage politics, polarisation and participation in Western Europe. West Eur. Polit. 0:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2161786

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Bozdag E (2013) Bias in algorithmic filtering and personalization. Ethics Inf Technol 15:209–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-013-9321-6

Bratton B (2021) AI urbanism: a design framework for governance, program, and platform cognition. AI Soc. 36:1307–1312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01121-9

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Cachat-Rosset G, Klarsfeld A (2023) Diversity, equity, and inclusion in Artificial Intelligence: An evaluation of guidelines. Appl Artif Intell 37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2023.2176618

Campo-Ruiz I (2024) Economic powers encompass the largest cultural buildings: market, culture and equality in Stockholm, Sweden (1918–2023). ArchNet-IJAR. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-06-2023-0160

Churchland PM, Churchland PS (1990) Could a machine think? Sci. Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci. 262:32–39

CAS

Google Scholar

Crawford K (2021) Atlas of AI: power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press, New Haven

Book

MATH

Google Scholar

Cugurullo F (2021) Frankenstein urbanism: eco, smart and autonomous cities, artificial intelligence and the end of the city. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London

Book

Google Scholar

Cugurullo F, Caprotti F, Cook M et al. (2024) The rise of AI urbanism in post-smart cities: a critical commentary on urban artificial intelligence. Urban Stud. 61:1168–1182. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231203386

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Cugurullo F (2020) Urban artificial intelligence: from automation to autonomy in the smart city. Front Sustain Cities 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2020.00038

Cugurullo F, Caprotti F, Cook M, Karvonen A, McGuirk P, Marvin S (eds.) (2023) Artificial intelligence and the city: urbanistic perspectives on AI, 1st edn. Taylor & Francis, London

Dervin F (2023) The paradoxes of interculturality: a toolbox of out-of-the-box ideas for intercultural communication education. Routledge, New York

MATH

Google Scholar

Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE (1988) Making a mind versus modeling the brain: Artificial Intelligence back at a branchpoint. Daedalus Camb. Mass 117:15–43

MATH

Google Scholar

Duberry J (2022) Artificial Intelligence and democracy: risks and promises of AI-mediated citizen-government relations. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton

Elena-Bucea A, Cruz-Jesus F, Oliveira T, Coelho PS (2021) Assessing the role of age, education, gender and income on the digital divide: evidence for the European Union. Inf. Syst. Front 23:1007–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10012-9

Article

Google Scholar

Elliott A (2018) The Culture of AI: everyday life and the digital revolution, 1st edn. Routledge, Milton

MATH

Google Scholar

von Eschenbach WJ (2021) Transparency and the black box problem: why we do not trust AI. Philos. Technol. 34:1607–1622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00477-0

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2024) Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj. Accessed 20 Sep 2024

Flikschuh K, Ypi L, Ajei M (2015) Kant and colonialism: historical and critical perspectives. University Press, Oxford

Forty A (2000) Words and buildings: a vocabulary of modern architecture. Thames & Hudson, London

Fosch-Villaronga E, Poulsen A (2022) Diversity and inclusion in Artificial Intelligence. In: Custers B, Fosch-Villaronga E (eds) Law and Artificial Intelligence: regulating AI and applying AI in legal practice. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague, p 109–134

Future of Life Institute (2023) Pause giant AI experiments: an open letter. In: Future Life Inst. https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/. Accessed 3 Sep 2024

George AS, George ASH, Martin ASG (2023) The environmental impact of AI: a case study of water consumption by Chat GPT. Part. Univers Int Innov. J. 1:97–104. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7855594

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Geschke D, Lorenz J, Holtz P (2019) The triple-filter bubble: Using agent-based modelling to test a meta-theoretical framework for the emergence of filter bubbles and echo chambers. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58:129–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12286

Article

PubMed

MATH

Google Scholar

Gupta R, Nair K, Mishra M et al. (2024) Adoption and impacts of generative artificial intelligence: theoretical underpinnings and research agenda. Int J. Inf. Manag Data Insights 4:100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2024.100232

Article

Google Scholar

Haandrikman K, Costa R, Malmberg B et al. (2023) Socio-economic segregation in European cities. A comparative study of Brussels, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Oslo and Stockholm. Urban Geogr. 44:1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1959778

Article

Google Scholar

Haria V, Shah Y, Gangwar V et al. (2019) The working of Google Maps, and the commercial usage of navigation systems. IJIRT 6:184–191

MATH

Google Scholar

Heckmann R, Kock S, Gaspers L (2022) Artificial intelligence supporting sustainable and individual mobility: development of an algorithm for mobility planning and choice of means of transport. In: Coors V, Pietruschka D, Zeitler B (eds) iCity. Transformative research for the livable, intelligent, and sustainable city. Springer International Publishing, Stuttgart, p 27–40

Henning M, Westlund H, Enflo K (2023) Urban–rural population changes and spatial inequalities in Sweden. Reg. Sci. Policy Pr. 15:878–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12602

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Howarth J (2024) Number of parameters in GPT-4 (Latest Data). https://explodingtopics.com/blog/gpt-parameters. Accessed 8 Sep 2024

Howe B, Brown JM, Han B, Herman B, Weber N, Yan A, Yang S, Yang Y (2022) Integrative urban AI to expand coverage, access, and equity of urban data. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 231:1741–1752. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjs/s11734-022-00475-z

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

MATH

Google Scholar

Jang KM, Chen J, Kang Y, Kim J, Lee J, Duarte F (2023) Understanding place identity with generative AI. Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Leibniz, pp 1–6

Kent N (2008) A concise history of Sweden. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book

MATH

Google Scholar

Khan I (2024a) The quick guide to prompt engineering. John Wiley & Sons, Newark

MATH

Google Scholar

Khan S (2024b) Cultural diversity and social cohesion: perspectives from social science. Phys. Educ. Health Soc. Sci. 2:40–48

MATH

Google Scholar

Lo Piano S (2020) Ethical principles in machine learning and artificial intelligence: cases from the field and possible ways forward. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0501-9

Luusua A, Ylipulli J, Foth M, Aurigi A (2023) Urban AI: understanding the emerging role of artificial intelligence in smart cities. AI Soc. 38:1039–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01537-5

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Lyu Y, Lu H, Lee MK, Schmitt G, Lim B (2024) IF-City: intelligible fair city planning to measure, explain and mitigate inequality. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput Graph 30:3749–3766. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2023.3239909

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Macrorie R, Marvin S, While A (2021) Robotics and automation in the city: a research agenda. Urban Geogr. 42(2):197–217

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Mahmud HJA (2013) Social cohesion in multicultural society: a case of Bangladeshi immigrants in Stockholm. Dissertation, Stockholm University

Marion G (2017) How Culture Affects Language and Dialogue. In: The Routledge Handbook of Language and Dialogue. Routledge, London

McNealy JE (2021) Framing and language of ethics: technology, persuasion, and cultural context. J. Soc. Comput 2:226–237. https://doi.org/10.23919/JSC.2021.0027

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

McQuire S (2019) One map to rule them all? Google Maps as digital technical object. Commun. Public 4:150–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047319850192

Article

Google Scholar

Mehta H, Kanani P, Lande P (2019) Google Maps. Int J. Comput. Appl 178:41–46. https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2019918791

Article

Google Scholar

Midjourney (2024) About. www.midjourney.com/home. Accessed 23 Oct 2024

Mironenko IA, Sorokin PS (2018) Seeking for the definition of “culture”: current concerns and their implications. a comment on Gustav Jahoda’s article “Critical reflections on some recent definitions of “culture’”. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 52:331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-018-9425-y

Article

PubMed

MATH

Google Scholar

Mozur P (2017) Beijing wants A.I. to be made in China by 2030. N. Y. Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/20/business/china-artificial-intelligence.html

Murdie RA, Borgegård L-E (1998) Immigration, spatial segregation and housing segmentation of immigrants in metropolitan Stockholm, 1960-95. Urban Stud. Edinb. Scotl. 35:1869–1888. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098984196

Article

Google Scholar

Musterd S, Marcińczak S, van Ham M, Tammaru T (2017) Socioeconomic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban Geogr. 38:1062–1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1228371

Article

Google Scholar

Newell A, Simon HA (1976) Computer science as empirical inquiry: symbols and search. Commun. ACM 19:113–126. https://doi.org/10.1145/360018.360022

Article

MathSciNet

MATH

Google Scholar

Norocel OC, Hellström A, Jørgensen MB (2020) Nostalgia and hope: intersections between politics of culture, welfare, and migration in Europe, 1st edn. Springer International Publishing, Cham

OECD (2019) Artificial Intelligence in Society. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eedfee77-en. Accessed 23 Oct 2024

OpenAI (2023) https://openai.com/about. Accessed 20 Sep 2024

Palmini O, Cugurullo F (2023) Charting AI urbanism: conceptual sources and spatial implications of urban artificial intelligence. Discov Artif Intell 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-023-00060-w

Pariser E (2011) The filter bubble: what the Internet is hiding from you. Viking, London

Parker PD, Van Zanden B, Marsh HW, Owen K, Duineveld J, Noetel M (2020) The intersection of gender, social class, and cultural context: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 32:197–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09493-1

Article

Google Scholar

Peng J, Strijker D, Wu Q (2020) Place identity: how far have we come in exploring its meanings? Front Psychol 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00294

Peng Z-R, Lu K-F, Liu Y, Zhai W (2023) The pathway of urban planning AI: from planning support to plan-making. J Plan Educ Res 0. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X231180568

Phuangsuwan P, Siripipatthanakul S, Limna P, Pariwongkhuntorn N (2024) The impact of Google Maps application on the digital economy. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 5:192–203. https://doi.org/10.22495/cbsrv5i1art18

Article

Google Scholar

Popelka S, Narvaez Zertuche L, Beroche H (2023) Urban AI guide. Urban AI. https://urbanai.fr/

Prabhakaran V, Qadri R, Hutchinson B (2022) Cultural incongruencies in Artificial Intelligence. ArXiv Cornell Univ. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2211.13069

Raile P (2024) The usefulness of ChatGPT for psychotherapists and patients. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:47–48. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02567-0

Article

Google Scholar

Rhodes SC (2022) Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and fake news: How social media conditions individuals to be less critical of political misinformation. Polit Commun 39:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1910887

Robertson RE, Green J, Ruck DJ, et al. (2023) Users choose to engage with more partisan news than they are exposed to on Google Search. Nature 618:342–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06078-5

Rönnblom M, Carlsson V, Öjehag‐Pettersson A (2023) Gender equality in Swedish AI policies. What’s the problem represented to be? Rev. Policy Res 40:688–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12547

Article

Google Scholar

Sabherwal R, Grover V (2024) The societal impacts of generative Artificial Intelligence: a balanced perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 25:13–22. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00860

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Sanchez TW, Shumway H, Gordner T, Lim T (2023) The prospects of Artificial Intelligence in urban planning. Int J. Urban Sci. 27:179–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2022.2102538

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Sareen S, Saltelli A, Rommetveit K (2020) Ethics of quantification: illumination, obfuscation and performative legitimation. Palgrave Commun 6. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0396-5

Searle J (1980) Minds, brains and programs. In: Collins A, Smith EE (eds) Readings in Cognitive Science. Morgan Kaufmann, San Mateo, p 20–31

Sherman S (2023) The polyopticon: a diagram for urban Artificial Intelligences. AI Soc. 38:1209–1222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01501-3

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Sloan RH, Warner R (2020) Beyond bias: Artificial Intelligence and social justice. Va J. Law Technol. 24:1

MATH

Google Scholar

Son TH, Weedon Z, Yigitcanlar T et al. (2023) Algorithmic urban planning for smart and sustainable development: Systematic review of the literature. Sustain Cities Soc. 94:104562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104562

Article

Google Scholar

Sun J, Song J, Jiang Y, et al. (2022) Prick the filter bubble: A novel cross domain recommendation model with adaptive diversity regularization. Electron Mark 32:101–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-021-00492-1

Tan L, Luhrs M (2024) Using generative AI Midjourney to enhance divergent and convergent thinking in an architect’s creative design process. Des. J. 27:677–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2024.2353479

Article

Google Scholar

Tseng Y-S (2023) Assemblage thinking as a methodology for studying urban AI phenomena. AI Soc. 38:1099–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01500-4

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Ullah Z, Al-Turjman F, Mostarda L, Gagliardi R (2020) Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in smart cities. Comput Commun. 154:313–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2020.02.069

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Verdegem P (2022) Dismantling AI capitalism: the commons as an alternative to the power concentration of Big Tech. AI Soc 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01437-8

Weizenbaum J (1984) Computer power and human reason: from judgment to calculation. Penguin, Harmondsworth

MATH

Google Scholar

Wu T, He S, Liu J et al. (2023) A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEECAA J. Autom. Sin. 10:1122–1136. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2023.123618

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Yigitcanlar T, Corchado JM, Mehmood R, Li RYM, Mossberger K, Desouza KC (2021) Responsible urban innovation with local government Artificial Intelligence (AI): A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Open Innov. 7:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010071

Article

Google Scholar

Zhang Q, Lu J, Jin Y (2021) Artificial Intelligence in recommender systems. Complex Intell. Syst. 7:439–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-020-00212-w

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Zhang J, Hu C (2023) Adaptive algorithms: users must be more vigilant. Nat Lond 618:907–907. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02033-6

You may like

Noticias

Apocalipsis Biosciencias para desarrollar Géminis para la infección en pacientes con quemaduras graves

Published

2 horas agoon

30 abril, 2025

– Esta nueva indicación es otro paso para desbloquear todo el potencial de la plataforma Gemini –

San Diego-(Business Wire)-$ Revb #GÉMINIS–Apocalipsis Biosciences, Inc. (NASDAQ: RevB) (la “empresa” o “revelación”), una compañía de ciencias de la vida de etapas clínicas que se centra en reequilibrar la inflamación para optimizar la salud, anunció una nueva indicación de objetivo para Géminis para la prevención de la infección en pacientes con quemaduras graves que requieren hospitalización (el Gema-PBI programa). El uso de Géminis para la prevención de la infección en pacientes con quemaduras severas, así como la prevención de la infección después de la cirugía (el Gema-PSI programa) son parte de la revelación familiar de patentes anteriormente con licencia de la Universidad de Vanderbilt.

“Estamos muy contentos de colaborar con el equipo de Apocalipsis para el avance de Géminis para la prevención de la infección en esta población de pacientes desatendida”, dijo Dra. Julia BohannonProfesor Asociado, Departamento de Anestesiología, Departamento de Patología, Microbiología e Inmunología, Universidad de Vanderbilt. “Creemos que la actividad de biomarcador clínico observada con Gemini se correlaciona fuertemente con nuestra experiencia preclínica en modelos de quemaduras de infecciones”.

El equipo de investigación de Vanderbilt demostrado El tratamiento posterior a la quemadura reduce significativamente la gravedad y la duración de la infección pulmonar de Pseudomonas, así como un nivel general reducido de inflamación en un modelo preclínico.

“La prevención de la infección en pacientes severamente quemados es un esfuerzo importante y complementa que la revelación laboral ha completado hasta la fecha”, dijo “, dijo”, dijo James RolkeCEO de Revelation “El programa Gemini-PBI puede ofrecer varias oportunidades regulatorias, de desarrollo y financiación que la compañía planea explorar”.

Sobre quemaduras e infección después de quemar

Las quemaduras son lesiones en la piel que involucran las dos capas principales: la epidermis externa delgada y/o la dermis más gruesa y profunda. Las quemaduras pueden ser el resultado de una variedad de causas que incluyen fuego, líquidos calientes, productos químicos (como ácidos fuertes o bases fuertes), electricidad, vapor, radiación de radiografías o radioterapia, luz solar o luz ultravioleta. Cada año, aproximadamente medio millón de estadounidenses sufren lesiones por quemaduras que requieren intervención médica. Si bien la mayoría de las lesiones por quemaduras no requieren ingreso a un hospital, se admiten alrededor de 40,000 pacientes, y aproximadamente 30,000 de ellos necesitan tratamiento especializado en un centro de quemaduras certificadas.

El número total anual de muertes relacionadas con quemaduras es de aproximadamente 3.400, siendo la infección invasiva la razón principal de la muerte después de las primeras 24 horas. La tasa de mortalidad general para pacientes con quemaduras graves es de aproximadamente 3.3%, pero esto aumenta al 20.6% en pacientes con quemaduras con lesión cutánea de quemaduras y inhalación, versus 10.5% por lesión por inhalación solo. La infección invasiva, incluida la sepsis, es la causa principal de la muerte después de la lesión por quemaduras, lo que representa aproximadamente el 51% de las muertes.

Actualmente no hay tratamientos aprobados para prevenir la infección sistémica en pacientes con quemaduras.

Sobre Géminis

Géminis es una formulación propietaria y propietaria de disacárido hexaacil fosforilada (PHAD (PHAD®) que reduce el daño asociado con la inflamación al reprogramarse del sistema inmune innato para responder al estrés (trauma, infección, etc.) de manera atenuada. La revelación ha realizado múltiples estudios preclínicos que demuestran el potencial terapéutico de Géminis en las indicaciones objetivo. Revelación anunciado previamente Datos clínicos positivos de fase 1 para el tratamiento intravenoso con Géminis. El punto final de seguridad primario se cumplió en el estudio de fase 1, y los resultados demostraron la actividad farmacodinámica estadísticamente significativa como se observó a través de los cambios esperados en múltiples biomarcadores, incluida la regulación positiva de IL-10.

Géminis se está desarrollando para múltiples indicaciones, incluso como pretratamiento para prevenir o reducir la gravedad y la duración de la lesión renal aguda (programa Gemini-AKI), y como pretratamiento para prevenir o reducir la gravedad y la duración de la infección posquirúrgica (programa GEMINI-PSI). Además, Gemini puede ser un tratamiento para detener o retrasar la progresión de la enfermedad renal crónica (programa Gemini-CKD).

Acerca de Apocalipsis Biosciences, Inc.

Revelation Biosciences, Inc. es una compañía de ciencias de la vida en estadio clínico centrada en aprovechar el poder de la inmunidad entrenada para la prevención y el tratamiento de la enfermedad utilizando su formulación patentada Géminis. Revelation tiene múltiples programas en curso para evaluar Géminis, incluso como prevención de la infección posquirúrgica, como prevención de lesiones renales agudas y para el tratamiento de la enfermedad renal crónica.

Para obtener más información sobre Apocalipsis, visite www.revbiosciences.com.

Declaraciones con avance

Este comunicado de prensa contiene declaraciones prospectivas definidas en la Ley de Reforma de Litigios de Valores Privados de 1995, según enmendada. Las declaraciones prospectivas son declaraciones que no son hechos históricos. Estas declaraciones prospectivas generalmente se identifican por las palabras “anticipar”, “creer”, “esperar”, “estimar”, “plan”, “perspectiva” y “proyecto” y otras expresiones similares. Advirtemos a los inversores que las declaraciones prospectivas se basan en las expectativas de la gerencia y son solo predicciones o declaraciones de las expectativas actuales e involucran riesgos, incertidumbres y otros factores conocidos y desconocidos que pueden hacer que los resultados reales sean materialmente diferentes de los previstos por las declaraciones de prospección. Apocalipsis advierte a los lectores que no depositen una dependencia indebida de tales declaraciones de vista hacia adelante, que solo hablan a partir de la fecha en que se hicieron. Los siguientes factores, entre otros, podrían hacer que los resultados reales difieran materialmente de los descritos en estas declaraciones prospectivas: la capacidad de la revelación para cumplir con sus objetivos financieros y estratégicos, debido a, entre otras cosas, la competencia; la capacidad de la revelación para crecer y gestionar la rentabilidad del crecimiento y retener a sus empleados clave; la posibilidad de que la revelación pueda verse afectada negativamente por otros factores económicos, comerciales y/o competitivos; riesgos relacionados con el desarrollo exitoso de los candidatos de productos de Apocalipsis; la capacidad de completar con éxito los estudios clínicos planificados de sus candidatos de productos; El riesgo de que no podamos inscribir completamente nuestros estudios clínicos o la inscripción llevará más tiempo de lo esperado; riesgos relacionados con la aparición de eventos de seguridad adversos y/o preocupaciones inesperadas que pueden surgir de los datos o análisis de nuestros estudios clínicos; cambios en las leyes o regulaciones aplicables; Iniciación esperada de los estudios clínicos, el momento de los datos clínicos; El resultado de los datos clínicos, incluido si los resultados de dicho estudio son positivos o si se puede replicar; El resultado de los datos recopilados, incluido si los resultados de dichos datos y/o correlación se pueden replicar; el momento, los costos, la conducta y el resultado de nuestros otros estudios clínicos; El tratamiento anticipado de datos clínicos futuros por parte de la FDA, la EMA u otras autoridades reguladoras, incluidos si dichos datos serán suficientes para su aprobación; el éxito de futuras actividades de desarrollo para sus candidatos de productos; posibles indicaciones para las cuales se pueden desarrollar candidatos de productos; la capacidad de revelación para mantener la lista de sus valores en NASDAQ; la duración esperada sobre la cual los saldos de Apocalipsis financiarán sus operaciones; y otros riesgos e incertidumbres descritos en este documento, así como aquellos riesgos e incertidumbres discutidos de vez en cuando en otros informes y otras presentaciones públicas con la SEC por Apocalipsis.

Contactos

Mike Porter

Relaciones con inversores

Porter Levay & Rose Inc.

Correo electrónico: mike@plrinvest.com

Chester Zygmont, III

Director financiero

Apocalipsis Biosciences Inc.

Correo electrónico: czygmont@revbiosciences.com

Noticias

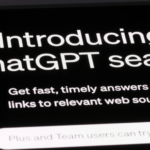

Why Google’s search engine trial is about AI : NPR

Published

10 horas agoon

29 abril, 2025

An illustration photograph taken on Feb. 20, 2025 shows Grok, DeepSeek and ChatGPT apps displayed on a phone screen. The Justice Department’s 2020 complaint against Google has few mentions of artificial intelligence or AI chatbots. But nearly five years later, as the remedy phase of the trial enters its second week of testimony, the focus has shifted to AI.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

When the U.S. Department of Justice originally brought — and then won — its case against Google, arguing that the tech behemoth monopolized the search engine market, the focus was on, well … search.

Back then, in 2020, the government’s antitrust complaint against Google had few mentions of artificial intelligence or AI chatbots. But nearly five years later, as the remedy phase of the trial enters its second week of testimony, the focus has shifted to AI, underscoring just how quickly this emerging technology has expanded.

In the past few days, before a federal judge who will assess penalties against Google, the DOJ has argued that the company could use its artificial intelligence products to strengthen its monopoly in online search — and to use the data from its powerful search index to become the dominant player in AI.

In his opening statements last Monday, David Dahlquist, the acting deputy director of the DOJ’s antitrust civil litigation division, argued that the court should consider remedies that could nip a potential Google AI monopoly in the bud. “This court’s remedy should be forward-looking and not ignore what is on the horizon,” he said.

Dahlquist argued that Google has created a system in which its control of search helps improve its AI products, sending more users back to Google search — creating a cycle that maintains the tech company’s dominance and blocks competitors out of both marketplaces.

The integration of search and Gemini, the company’s AI chatbot — which the DOJ sees as powerful fuel for this cycle — is a big focus of the government’s proposed remedies. The DOJ is arguing that to be most effective, those remedies must address all ways users access Google search, so any penalties approved by the court that don’t include Gemini (or other Google AI products now or in the future) would undermine their broader efforts.

Department of Justice lawyer David Dahlquist leaves the Washington, D.C. federal courthouse on Sept. 20, 2023 during the original trial phase of the antitrust case against Google.

Jose Luis Magana/AP/FR159526 AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Jose Luis Magana/AP/FR159526 AP

AI and search are connected like this: Search engine indices are essentially giant databases of pages and information on the web. Google has its own such index, which contains hundreds of billions of webpages and is over 100,000,000 gigabytes, according to court documents. This is the data Google’s search engine scans when responding to a user’s query.

AI developers use these kinds of databases to build and train the models used to power chatbots. In court, attorneys for the DOJ have argued that Google’s Gemini pulls information from the company’s search index, including citing search links and results, extending what they say is a self-serving cycle. They argue that Google’s ability to monopolize the search market gives it user data, at a huge scale — an advantage over other AI developers.

The Justice Department argues Google’s monopoly over search could have a direct effect on the development of generative AI, a type of artificial intelligence that uses existing data to create new content like text, videos or photos, based on a user’s prompts or questions. Last week, the government called executives from several major AI companies, like OpenAI and Perplexity, in an attempt to argue that Google’s stranglehold on search is preventing some of those companies from truly growing.

The government argues that to level the playing field, Google should be forced to open its search data — like users’ search queries, clicks and results — and license it to other competitors at a cost.

This is on top of demands related to Google’s search engine business, most notably that it should be forced to sell off its Chrome browser.

Google flatly rejects the argument that it could monopolize the field of generative AI, saying competition in the AI race is healthy. In a recent blog post on Google’s website, Lee-Anne Mulholland, the company’s vice president of regulatory affairs, wrote that since the federal judge first ruled against Google over a year ago, “AI has already rapidly reshaped the industry, with new entrants and new ways of finding information, making it even more competitive.”

In court, Google’s lawyers have argued that there are a host of AI companies with chatbots — some of which are outperforming Gemini. OpenAI has ChatGPT, Meta has MetaAI and Perplexity has Perplexity AI.

“There is no shortage of competition in that market, and ChatGPT and Meta are way ahead of everybody in terms of the distribution and usage at this point,” said John E. Schmidtlein, a lawyer for Google, during his opening statement. “But don’t take my word for it. Look at the data. Hundreds and hundreds of millions of downloads by ChatGPT.”

Competing in a growing AI field

It should be no surprise that AI is coming up so much at this point in the trial, said Alissa Cooper, the executive director of the Knight-Georgetown Institute, a nonpartisan tech research and policy center at Georgetown University focusing on AI, disinformation and data privacy.

“If you look at search as a product today, you can’t really think about search without thinking about AI,” she said. “I think the case is a really great opportunity to try to … analyze how Google has benefited specifically from the monopoly that it has in search, and ensure that the behavior that led to that can’t be used to gain an unfair advantage in these other markets which are more nascent.”

Having access to Google’s data, she said, “would provide them with the ability to build better chatbots, build better search engines, and potentially build other products that we haven’t even thought of.”

To make that point, the DOJ called Nick Turley, OpenAI’s head of product for ChatGPT, to the stand last Tuesday. During a long day of testimony, Turley detailed how without access to Google’s search index and data, engineers for the growing company tried to build their own.

ChatGPT, a large language model that can generate human-like responses, engage in conversations and perform tasks like explaining a tough-to-understand math lesson, was never intended to be a product for OpenAI, Turley said. But once it launched and went viral, the company found that people were using it for a host of needs.

Though popular, ChatGPT had its drawbacks, like the bot’s limited “knowledge,” Turley said. Early on, ChatGPT was not connected to the internet and could only use information that it had been fed up to a certain point in its training. For example, Turley said, if a user asked “Who is the president?” the program would give a 2022 answer — from when its “knowledge” effectively stopped.

OpenAI couldn’t build their own index fast enough to address their problems; they found that process incredibly expensive, time consuming and potentially years from coming to fruition, Turley said.

So instead, they sought a partnership with a third party search provider. At one point, OpenAI tried to make a deal with Google to gain access to their search, but Google declined, seeing OpenAI as a direct competitor, Turley testified.

But Google says companies like OpenAI are doing just fine without gaining access to the tech giant’s own technology — which it spent decades developing. These companies just want “handouts,” said Schmidtlein.

On the third day of the remedy trial, internal Google documents shared in court by the company’s lawyers compared how many people are using Gemini versus its competitors. According to those documents, ChatGPT and MetaAI are the two leaders, with Gemini coming in third.

They showed that this March, Gemini saw 35 million active daily users and 350 million monthly active users worldwide. That was up from 9 million daily active users in October 2024. But according to those documents, Gemini was still lagging behind ChatGPT, which reached 160 million daily users and around 600 million active users in March.

These numbers show that competitors have no need to use Google’s search data, valuable intellectual property that the tech giant spent decades building and maintaining, the company argues.

“The notion that somehow ChatGPT can’t get distribution is absurd,” Schmidtlein said in court last week. “They have more distribution than anyone.”

Google’s exclusive deals

In his ruling last year, U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta said Google’s exclusive agreements with device makers, like Apple and Samsung, to make its search engine the default on those companies’ phones helped maintain its monopoly. It remains a core issue for this remedy trial.

Now, the DOJ is arguing that Google’s deals with device manufacturers are also directly affecting AI companies and AI tech.

In court, the DOJ argued that Google has replicated this kind of distribution deal by agreeing to pay Samsung what Dahlquist called a monthly “enormous sum” for Gemini to be installed on smartphones and other devices.

Last Wednesday, the DOJ also called Dmitry Shevelenko, Perplexity’s chief business officer, to testify that Google has effectively cut his company out from making deals with manufacturers and mobile carriers.

Perplexity AIs not preloaded on any mobile devices in the U.S., despite many efforts to get phone companies to establish Perplexity as a default or exclusive app on devices, Shevelenko said. He compared Google’s control in that space to that of a “mob boss.”

But Google’s attorney, Christopher Yeager, noted in questioning Shevelenko that Perplexity has reached a valuation of over $9 billion — insinuating the company is doing just fine in the marketplace.

Despite testifying in court (for which he was subpoenaed, Shevelenko noted), he and other leaders at Perplexity are against the breakup of Google. In a statement on the company’s website, the Perplexity team wrote that neither forcing Google to sell off Chrome nor to license search data to its competitors are the best solutions. “Neither of these address the root issue: consumers deserve choice,” they wrote.

Google and Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai departs federal court after testifying in October 2023 in Washington, DC. Pichai testified to defend his company in the original antitrust trial. Pichai is expected to testify again during the remedy phase of the legal proceedings.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Drew Angerer/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

What to expect next

This week the trial continues, with the DOJ calling its final witnesses this morning to testify about the feasibility of a Chrome divestiture and how the government’s proposed remedies would help rivals compete. On Tuesday afternoon, Google will begin presenting its case, which is expected to feature the testimony of CEO Sundar Pichai, although the date of his appearance has not been specified.

Closing arguments are expected at the end of May, and then Mehta will make his ruling. Google says once this phase is settled the company will appeal Mehta’s ruling in the underlying case.

Whatever Mehta decides in this remedy phase, Cooper thinks it will have effects beyond just the business of search engines. No matter what it is, she said, “it will be having some kind of impact on AI.”

Google is a financial supporter of NPR.

Noticias

API de Meta Oleleshes Llama que se ejecuta 18 veces más rápido que OpenAI: Cerebras Partnership ofrece 2.600 tokens por segundo

Published

11 horas agoon

29 abril, 2025

Únase a nuestros boletines diarios y semanales para obtener las últimas actualizaciones y contenido exclusivo sobre la cobertura de IA líder de la industria. Obtenga más información

Meta anunció hoy una asociación con Cerebras Systems para alimentar su nueva API de LLAMA, ofreciendo a los desarrolladores acceso a velocidades de inferencia hasta 18 veces más rápido que las soluciones tradicionales basadas en GPU.

El anuncio, realizado en la Conferencia inaugural de desarrolladores de Llamacon de Meta en Menlo Park, posiciona a la compañía para competir directamente con Operai, Anthrope y Google en el mercado de servicios de inferencia de IA en rápido crecimiento, donde los desarrolladores compran tokens por miles de millones para impulsar sus aplicaciones.

“Meta ha seleccionado a Cerebras para colaborar para ofrecer la inferencia ultra rápida que necesitan para servir a los desarrolladores a través de su nueva API de LLAMA”, dijo Julie Shin Choi, directora de marketing de Cerebras, durante una sesión de prensa. “En Cerebras estamos muy, muy emocionados de anunciar nuestra primera asociación HyperScaler CSP para ofrecer una inferencia ultra rápida a todos los desarrolladores”.

La asociación marca la entrada formal de Meta en el negocio de la venta de AI Computation, transformando sus populares modelos de llama de código abierto en un servicio comercial. Si bien los modelos de LLAMA de Meta se han acumulado en mil millones de descargas, hasta ahora la compañía no había ofrecido una infraestructura en la nube de primera parte para que los desarrolladores creen aplicaciones con ellos.

“Esto es muy emocionante, incluso sin hablar sobre cerebras específicamente”, dijo James Wang, un ejecutivo senior de Cerebras. “Openai, Anthrope, Google: han construido un nuevo negocio de IA completamente nuevo desde cero, que es el negocio de inferencia de IA. Los desarrolladores que están construyendo aplicaciones de IA comprarán tokens por millones, a veces por miles de millones. Y estas son como las nuevas instrucciones de cómputo que las personas necesitan para construir aplicaciones AI”.

Breaking the Speed Barrier: Cómo modelos de Llama de Cerebras Supercharges

Lo que distingue a la oferta de Meta es el aumento de la velocidad dramática proporcionado por los chips de IA especializados de Cerebras. El sistema de cerebras ofrece más de 2.600 fichas por segundo para Llama 4 Scout, en comparación con aproximadamente 130 tokens por segundo para ChatGPT y alrededor de 25 tokens por segundo para Deepseek, según puntos de referencia del análisis artificial.

“Si solo se compara con API a API, Gemini y GPT, todos son grandes modelos, pero todos se ejecutan a velocidades de GPU, que son aproximadamente 100 tokens por segundo”, explicó Wang. “Y 100 tokens por segundo están bien para el chat, pero es muy lento para el razonamiento. Es muy lento para los agentes. Y la gente está luchando con eso hoy”.

Esta ventaja de velocidad permite categorías completamente nuevas de aplicaciones que antes no eran prácticas, incluidos los agentes en tiempo real, los sistemas de voz de baja latencia conversacional, la generación de código interactivo y el razonamiento instantáneo de múltiples pasos, todos los cuales requieren encadenamiento de múltiples llamadas de modelo de lenguaje grandes que ahora se pueden completar en segundos en lugar de minutos.

La API de LLAMA representa un cambio significativo en la estrategia de IA de Meta, en la transición de ser un proveedor de modelos a convertirse en una compañía de infraestructura de IA de servicio completo. Al ofrecer un servicio API, Meta está creando un flujo de ingresos a partir de sus inversiones de IA mientras mantiene su compromiso de abrir modelos.

“Meta ahora está en el negocio de vender tokens, y es excelente para el tipo de ecosistema de IA estadounidense”, señaló Wang durante la conferencia de prensa. “Traen mucho a la mesa”.

La API ofrecerá herramientas para el ajuste y la evaluación, comenzando con el modelo LLAMA 3.3 8B, permitiendo a los desarrolladores generar datos, entrenar y probar la calidad de sus modelos personalizados. Meta enfatiza que no utilizará datos de clientes para capacitar a sus propios modelos, y los modelos construidos con la API de LLAMA se pueden transferir a otros hosts, una clara diferenciación de los enfoques más cerrados de algunos competidores.

Las cerebras alimentarán el nuevo servicio de Meta a través de su red de centros de datos ubicados en toda América del Norte, incluidas las instalaciones en Dallas, Oklahoma, Minnesota, Montreal y California.

“Todos nuestros centros de datos que sirven a la inferencia están en América del Norte en este momento”, explicó Choi. “Serviremos Meta con toda la capacidad de las cerebras. La carga de trabajo se equilibrará en todos estos diferentes centros de datos”.

El arreglo comercial sigue lo que Choi describió como “el proveedor de cómputo clásico para un modelo hiperscalador”, similar a la forma en que NVIDIA proporciona hardware a los principales proveedores de la nube. “Están reservando bloques de nuestro cómputo para que puedan servir a su población de desarrolladores”, dijo.

Más allá de las cerebras, Meta también ha anunciado una asociación con Groq para proporcionar opciones de inferencia rápida, brindando a los desarrolladores múltiples alternativas de alto rendimiento más allá de la inferencia tradicional basada en GPU.

La entrada de Meta en el mercado de API de inferencia con métricas de rendimiento superiores podría potencialmente alterar el orden establecido dominado por Operai, Google y Anthrope. Al combinar la popularidad de sus modelos de código abierto con capacidades de inferencia dramáticamente más rápidas, Meta se está posicionando como un competidor formidable en el espacio comercial de IA.

“Meta está en una posición única con 3 mil millones de usuarios, centros de datos de hiper escala y un gran ecosistema de desarrolladores”, según los materiales de presentación de Cerebras. La integración de la tecnología de cerebras “ayuda a Meta Leapfrog OpenAi y Google en rendimiento en aproximadamente 20X”.

Para las cerebras, esta asociación representa un hito importante y la validación de su enfoque especializado de hardware de IA. “Hemos estado construyendo este motor a escala de obleas durante años, y siempre supimos que la primera tarifa de la tecnología, pero en última instancia tiene que terminar como parte de la nube de hiperescala de otra persona. Ese fue el objetivo final desde una perspectiva de estrategia comercial, y finalmente hemos alcanzado ese hito”, dijo Wang.

La API de LLAMA está actualmente disponible como una vista previa limitada, con Meta planifica un despliegue más amplio en las próximas semanas y meses. Los desarrolladores interesados en acceder a la inferencia Ultra-Fast Llama 4 pueden solicitar el acceso temprano seleccionando cerebras de las opciones del modelo dentro de la API de LLAMA.

“Si te imaginas a un desarrollador que no sabe nada sobre cerebras porque somos una empresa relativamente pequeña, solo pueden hacer clic en dos botones en el SDK estándar de SDK estándar de Meta, generar una tecla API, seleccionar la bandera de cerebras y luego, de repente, sus tokens se procesan en un motor gigante a escala de dafers”, explicó las cejas. “Ese tipo de hacernos estar en el back -end del ecosistema de desarrolladores de Meta todo el ecosistema es tremendo para nosotros”.

La elección de Meta de silicio especializada señala algo profundo: en la siguiente fase de la IA, no es solo lo que saben sus modelos, sino lo rápido que pueden pensarlo. En ese futuro, la velocidad no es solo una característica, es todo el punto.

Insights diarias sobre casos de uso comercial con VB diariamente

Si quieres impresionar a tu jefe, VB Daily te tiene cubierto. Le damos la cuenta interior de lo que las empresas están haciendo con la IA generativa, desde cambios regulatorios hasta implementaciones prácticas, por lo que puede compartir ideas para el ROI máximo.

Lea nuestra Política de privacidad

Gracias por suscribirse. Mira más boletines de VB aquí.

Ocurrió un error.

Related posts

Trending

-

Startups11 meses ago

Startups11 meses agoRemove.bg: La Revolución en la Edición de Imágenes que Debes Conocer

-

Tutoriales12 meses ago

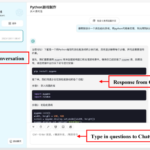

Tutoriales12 meses agoCómo Comenzar a Utilizar ChatGPT: Una Guía Completa para Principiantes

-

Recursos12 meses ago

Recursos12 meses agoCómo Empezar con Popai.pro: Tu Espacio Personal de IA – Guía Completa, Instalación, Versiones y Precios

-

Startups10 meses ago

Startups10 meses agoStartups de IA en EE.UU. que han recaudado más de $100M en 2024

-

Startups12 meses ago

Startups12 meses agoDeepgram: Revolucionando el Reconocimiento de Voz con IA

-

Recursos11 meses ago

Recursos11 meses agoPerplexity aplicado al Marketing Digital y Estrategias SEO

-

Recursos12 meses ago

Recursos12 meses agoSuno.com: La Revolución en la Creación Musical con Inteligencia Artificial

-

Noticias10 meses ago

Noticias10 meses agoDos periodistas octogenarios deman a ChatGPT por robar su trabajo

Inside the OpenAI-DeepSeek Distillation Saga & Alibaba’s Most Powerful AI Model Qwen2.5-Max

Inside the OpenAI-DeepSeek Distillation Saga & Alibaba’s Most Powerful AI Model Qwen2.5-Max

De ChatGPT a mil millones de agentes

De ChatGPT a mil millones de agentes