Noticias

Artificial intelligence may affect diversity: architecture and cultural context reflected through ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Google Maps

Published

1 año agoon

Adobor H (2021) Open strategy: what is the impact of national culture? Manag Res Rev. 44:1277–1297. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-06-2020-0334

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Airoldi M, Rokka J (2022) Algorithmic consumer culture. Consum Mark. Cult. 25:411–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2022.2084726

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Ali T, Marc B, Omar B et al. (2021) Exploring destination’s negative e-reputation using aspect-based sentiment analysis approach: case of Marrakech destination on TripAdvisor. Tour. Manag Perspect. 40:100892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100892

Article

Google Scholar

Andersson R, Bråmå Å (2018) The Stockholm estates: a tale of the importance of initial conditions, macroeconomic dependencies, tenure and immigration. In: Hess D, Tammaru T, van Ham M (eds.) Housing estates in Europe, 1st edn. Springer, Cham, p 361–388

Anon (2023) How to worry wisely about artificial intelligence. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/04/20/how-to-worry-wisely-about-artificial-intelligence

Berman A, de Fine Licht K, Carlsson V (2024) Trustworthy AI in the public sector: an empirical analysis of a Swedish labor market decision-support system. Technol. Soc. 76:102471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102471

Article

Google Scholar

Bircan T, Korkmaz EE (2021) Big data for whose sake? Governing migration through artificial intelligence. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00910-x

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Borbáth E, Hutter S, Leininger A (2023) Cleavage politics, polarisation and participation in Western Europe. West Eur. Polit. 0:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2161786

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Bozdag E (2013) Bias in algorithmic filtering and personalization. Ethics Inf Technol 15:209–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-013-9321-6

Bratton B (2021) AI urbanism: a design framework for governance, program, and platform cognition. AI Soc. 36:1307–1312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01121-9

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Cachat-Rosset G, Klarsfeld A (2023) Diversity, equity, and inclusion in Artificial Intelligence: An evaluation of guidelines. Appl Artif Intell 37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2023.2176618

Campo-Ruiz I (2024) Economic powers encompass the largest cultural buildings: market, culture and equality in Stockholm, Sweden (1918–2023). ArchNet-IJAR. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-06-2023-0160

Churchland PM, Churchland PS (1990) Could a machine think? Sci. Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci. 262:32–39

CAS

Google Scholar

Crawford K (2021) Atlas of AI: power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press, New Haven

Book

MATH

Google Scholar

Cugurullo F (2021) Frankenstein urbanism: eco, smart and autonomous cities, artificial intelligence and the end of the city. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London

Book

Google Scholar

Cugurullo F, Caprotti F, Cook M et al. (2024) The rise of AI urbanism in post-smart cities: a critical commentary on urban artificial intelligence. Urban Stud. 61:1168–1182. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231203386

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Cugurullo F (2020) Urban artificial intelligence: from automation to autonomy in the smart city. Front Sustain Cities 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2020.00038

Cugurullo F, Caprotti F, Cook M, Karvonen A, McGuirk P, Marvin S (eds.) (2023) Artificial intelligence and the city: urbanistic perspectives on AI, 1st edn. Taylor & Francis, London

Dervin F (2023) The paradoxes of interculturality: a toolbox of out-of-the-box ideas for intercultural communication education. Routledge, New York

MATH

Google Scholar

Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE (1988) Making a mind versus modeling the brain: Artificial Intelligence back at a branchpoint. Daedalus Camb. Mass 117:15–43

MATH

Google Scholar

Duberry J (2022) Artificial Intelligence and democracy: risks and promises of AI-mediated citizen-government relations. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton

Elena-Bucea A, Cruz-Jesus F, Oliveira T, Coelho PS (2021) Assessing the role of age, education, gender and income on the digital divide: evidence for the European Union. Inf. Syst. Front 23:1007–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10012-9

Article

Google Scholar

Elliott A (2018) The Culture of AI: everyday life and the digital revolution, 1st edn. Routledge, Milton

MATH

Google Scholar

von Eschenbach WJ (2021) Transparency and the black box problem: why we do not trust AI. Philos. Technol. 34:1607–1622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00477-0

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2024) Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj. Accessed 20 Sep 2024

Flikschuh K, Ypi L, Ajei M (2015) Kant and colonialism: historical and critical perspectives. University Press, Oxford

Forty A (2000) Words and buildings: a vocabulary of modern architecture. Thames & Hudson, London

Fosch-Villaronga E, Poulsen A (2022) Diversity and inclusion in Artificial Intelligence. In: Custers B, Fosch-Villaronga E (eds) Law and Artificial Intelligence: regulating AI and applying AI in legal practice. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague, p 109–134

Future of Life Institute (2023) Pause giant AI experiments: an open letter. In: Future Life Inst. https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/. Accessed 3 Sep 2024

George AS, George ASH, Martin ASG (2023) The environmental impact of AI: a case study of water consumption by Chat GPT. Part. Univers Int Innov. J. 1:97–104. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7855594

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Geschke D, Lorenz J, Holtz P (2019) The triple-filter bubble: Using agent-based modelling to test a meta-theoretical framework for the emergence of filter bubbles and echo chambers. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58:129–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12286

Article

PubMed

MATH

Google Scholar

Gupta R, Nair K, Mishra M et al. (2024) Adoption and impacts of generative artificial intelligence: theoretical underpinnings and research agenda. Int J. Inf. Manag Data Insights 4:100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2024.100232

Article

Google Scholar

Haandrikman K, Costa R, Malmberg B et al. (2023) Socio-economic segregation in European cities. A comparative study of Brussels, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Oslo and Stockholm. Urban Geogr. 44:1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1959778

Article

Google Scholar

Haria V, Shah Y, Gangwar V et al. (2019) The working of Google Maps, and the commercial usage of navigation systems. IJIRT 6:184–191

MATH

Google Scholar

Heckmann R, Kock S, Gaspers L (2022) Artificial intelligence supporting sustainable and individual mobility: development of an algorithm for mobility planning and choice of means of transport. In: Coors V, Pietruschka D, Zeitler B (eds) iCity. Transformative research for the livable, intelligent, and sustainable city. Springer International Publishing, Stuttgart, p 27–40

Henning M, Westlund H, Enflo K (2023) Urban–rural population changes and spatial inequalities in Sweden. Reg. Sci. Policy Pr. 15:878–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12602

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Howarth J (2024) Number of parameters in GPT-4 (Latest Data). https://explodingtopics.com/blog/gpt-parameters. Accessed 8 Sep 2024

Howe B, Brown JM, Han B, Herman B, Weber N, Yan A, Yang S, Yang Y (2022) Integrative urban AI to expand coverage, access, and equity of urban data. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 231:1741–1752. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjs/s11734-022-00475-z

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

MATH

Google Scholar

Jang KM, Chen J, Kang Y, Kim J, Lee J, Duarte F (2023) Understanding place identity with generative AI. Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Leibniz, pp 1–6

Kent N (2008) A concise history of Sweden. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book

MATH

Google Scholar

Khan I (2024a) The quick guide to prompt engineering. John Wiley & Sons, Newark

MATH

Google Scholar

Khan S (2024b) Cultural diversity and social cohesion: perspectives from social science. Phys. Educ. Health Soc. Sci. 2:40–48

MATH

Google Scholar

Lo Piano S (2020) Ethical principles in machine learning and artificial intelligence: cases from the field and possible ways forward. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0501-9

Luusua A, Ylipulli J, Foth M, Aurigi A (2023) Urban AI: understanding the emerging role of artificial intelligence in smart cities. AI Soc. 38:1039–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01537-5

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Lyu Y, Lu H, Lee MK, Schmitt G, Lim B (2024) IF-City: intelligible fair city planning to measure, explain and mitigate inequality. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput Graph 30:3749–3766. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2023.3239909

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Macrorie R, Marvin S, While A (2021) Robotics and automation in the city: a research agenda. Urban Geogr. 42(2):197–217

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Mahmud HJA (2013) Social cohesion in multicultural society: a case of Bangladeshi immigrants in Stockholm. Dissertation, Stockholm University

Marion G (2017) How Culture Affects Language and Dialogue. In: The Routledge Handbook of Language and Dialogue. Routledge, London

McNealy JE (2021) Framing and language of ethics: technology, persuasion, and cultural context. J. Soc. Comput 2:226–237. https://doi.org/10.23919/JSC.2021.0027

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

McQuire S (2019) One map to rule them all? Google Maps as digital technical object. Commun. Public 4:150–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047319850192

Article

Google Scholar

Mehta H, Kanani P, Lande P (2019) Google Maps. Int J. Comput. Appl 178:41–46. https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2019918791

Article

Google Scholar

Midjourney (2024) About. www.midjourney.com/home. Accessed 23 Oct 2024

Mironenko IA, Sorokin PS (2018) Seeking for the definition of “culture”: current concerns and their implications. a comment on Gustav Jahoda’s article “Critical reflections on some recent definitions of “culture’”. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 52:331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-018-9425-y

Article

PubMed

MATH

Google Scholar

Mozur P (2017) Beijing wants A.I. to be made in China by 2030. N. Y. Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/20/business/china-artificial-intelligence.html

Murdie RA, Borgegård L-E (1998) Immigration, spatial segregation and housing segmentation of immigrants in metropolitan Stockholm, 1960-95. Urban Stud. Edinb. Scotl. 35:1869–1888. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098984196

Article

Google Scholar

Musterd S, Marcińczak S, van Ham M, Tammaru T (2017) Socioeconomic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban Geogr. 38:1062–1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1228371

Article

Google Scholar

Newell A, Simon HA (1976) Computer science as empirical inquiry: symbols and search. Commun. ACM 19:113–126. https://doi.org/10.1145/360018.360022

Article

MathSciNet

MATH

Google Scholar

Norocel OC, Hellström A, Jørgensen MB (2020) Nostalgia and hope: intersections between politics of culture, welfare, and migration in Europe, 1st edn. Springer International Publishing, Cham

OECD (2019) Artificial Intelligence in Society. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eedfee77-en. Accessed 23 Oct 2024

OpenAI (2023) https://openai.com/about. Accessed 20 Sep 2024

Palmini O, Cugurullo F (2023) Charting AI urbanism: conceptual sources and spatial implications of urban artificial intelligence. Discov Artif Intell 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-023-00060-w

Pariser E (2011) The filter bubble: what the Internet is hiding from you. Viking, London

Parker PD, Van Zanden B, Marsh HW, Owen K, Duineveld J, Noetel M (2020) The intersection of gender, social class, and cultural context: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 32:197–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09493-1

Article

Google Scholar

Peng J, Strijker D, Wu Q (2020) Place identity: how far have we come in exploring its meanings? Front Psychol 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00294

Peng Z-R, Lu K-F, Liu Y, Zhai W (2023) The pathway of urban planning AI: from planning support to plan-making. J Plan Educ Res 0. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X231180568

Phuangsuwan P, Siripipatthanakul S, Limna P, Pariwongkhuntorn N (2024) The impact of Google Maps application on the digital economy. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 5:192–203. https://doi.org/10.22495/cbsrv5i1art18

Article

Google Scholar

Popelka S, Narvaez Zertuche L, Beroche H (2023) Urban AI guide. Urban AI. https://urbanai.fr/

Prabhakaran V, Qadri R, Hutchinson B (2022) Cultural incongruencies in Artificial Intelligence. ArXiv Cornell Univ. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2211.13069

Raile P (2024) The usefulness of ChatGPT for psychotherapists and patients. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:47–48. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02567-0

Article

Google Scholar

Rhodes SC (2022) Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and fake news: How social media conditions individuals to be less critical of political misinformation. Polit Commun 39:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1910887

Robertson RE, Green J, Ruck DJ, et al. (2023) Users choose to engage with more partisan news than they are exposed to on Google Search. Nature 618:342–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06078-5

Rönnblom M, Carlsson V, Öjehag‐Pettersson A (2023) Gender equality in Swedish AI policies. What’s the problem represented to be? Rev. Policy Res 40:688–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12547

Article

Google Scholar

Sabherwal R, Grover V (2024) The societal impacts of generative Artificial Intelligence: a balanced perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 25:13–22. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00860

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Sanchez TW, Shumway H, Gordner T, Lim T (2023) The prospects of Artificial Intelligence in urban planning. Int J. Urban Sci. 27:179–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2022.2102538

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Sareen S, Saltelli A, Rommetveit K (2020) Ethics of quantification: illumination, obfuscation and performative legitimation. Palgrave Commun 6. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0396-5

Searle J (1980) Minds, brains and programs. In: Collins A, Smith EE (eds) Readings in Cognitive Science. Morgan Kaufmann, San Mateo, p 20–31

Sherman S (2023) The polyopticon: a diagram for urban Artificial Intelligences. AI Soc. 38:1209–1222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01501-3

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Sloan RH, Warner R (2020) Beyond bias: Artificial Intelligence and social justice. Va J. Law Technol. 24:1

MATH

Google Scholar

Son TH, Weedon Z, Yigitcanlar T et al. (2023) Algorithmic urban planning for smart and sustainable development: Systematic review of the literature. Sustain Cities Soc. 94:104562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104562

Article

Google Scholar

Sun J, Song J, Jiang Y, et al. (2022) Prick the filter bubble: A novel cross domain recommendation model with adaptive diversity regularization. Electron Mark 32:101–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-021-00492-1

Tan L, Luhrs M (2024) Using generative AI Midjourney to enhance divergent and convergent thinking in an architect’s creative design process. Des. J. 27:677–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2024.2353479

Article

Google Scholar

Tseng Y-S (2023) Assemblage thinking as a methodology for studying urban AI phenomena. AI Soc. 38:1099–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01500-4

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Ullah Z, Al-Turjman F, Mostarda L, Gagliardi R (2020) Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in smart cities. Comput Commun. 154:313–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2020.02.069

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Verdegem P (2022) Dismantling AI capitalism: the commons as an alternative to the power concentration of Big Tech. AI Soc 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01437-8

Weizenbaum J (1984) Computer power and human reason: from judgment to calculation. Penguin, Harmondsworth

MATH

Google Scholar

Wu T, He S, Liu J et al. (2023) A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEECAA J. Autom. Sin. 10:1122–1136. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2023.123618

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Yigitcanlar T, Corchado JM, Mehmood R, Li RYM, Mossberger K, Desouza KC (2021) Responsible urban innovation with local government Artificial Intelligence (AI): A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Open Innov. 7:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010071

Article

Google Scholar

Zhang Q, Lu J, Jin Y (2021) Artificial Intelligence in recommender systems. Complex Intell. Syst. 7:439–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-020-00212-w

Article

MATH

Google Scholar

Zhang J, Hu C (2023) Adaptive algorithms: users must be more vigilant. Nat Lond 618:907–907. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02033-6

You may like

Noticias

Revivir el compromiso en el aula de español: un desafío musical con chatgpt – enfoque de la facultad

Published

8 meses agoon

6 junio, 2025

A mitad del semestre, no es raro notar un cambio en los niveles de energía de sus alumnos (Baghurst y Kelley, 2013; Kumari et al., 2021). El entusiasmo inicial por aprender un idioma extranjero puede disminuir a medida que otros cursos con tareas exigentes compitan por su atención. Algunos estudiantes priorizan las materias que perciben como más directamente vinculadas a su especialidad o carrera, mientras que otros simplemente sienten el peso del agotamiento de mediados de semestre. En la primavera, los largos meses de invierno pueden aumentar esta fatiga, lo que hace que sea aún más difícil mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos (Rohan y Sigmon, 2000).

Este es el momento en que un instructor de idiomas debe pivotar, cambiando la dinámica del aula para reavivar la curiosidad y la motivación. Aunque los instructores se esfuerzan por incorporar actividades que se adapten a los cinco estilos de aprendizaje preferidos (Felder y Henriques, 1995)-Visual (aprendizaje a través de imágenes y comprensión espacial), auditivo (aprendizaje a través de la escucha y discusión), lectura/escritura (aprendizaje a través de interacción basada en texto), Kinesthetic (aprendizaje a través de movimiento y actividades prácticas) y multimodal (una combinación de múltiples estilos)-its is beneficiales). Estructurado y, después de un tiempo, clases predecibles con actividades que rompen el molde. La introducción de algo inesperado y diferente de la dinámica del aula establecida puede revitalizar a los estudiantes, fomentar la creatividad y mejorar su entusiasmo por el aprendizaje.

La música, en particular, ha sido durante mucho tiempo un aliado de instructores que enseñan un segundo idioma (L2), un idioma aprendido después de la lengua nativa, especialmente desde que el campo hizo la transición hacia un enfoque más comunicativo. Arraigado en la interacción y la aplicación del mundo real, el enfoque comunicativo prioriza el compromiso significativo sobre la memorización de memoria, ayudando a los estudiantes a desarrollar fluidez de formas naturales e inmersivas. La investigación ha destacado constantemente los beneficios de la música en la adquisición de L2, desde mejorar la pronunciación y las habilidades de escucha hasta mejorar la retención de vocabulario y la comprensión cultural (DeGrave, 2019; Kumar et al. 2022; Nuessel y Marshall, 2008; Vidal y Nordgren, 2024).

Sobre la base de esta tradición, la actividad que compartiremos aquí no solo incorpora música sino que también integra inteligencia artificial, agregando una nueva capa de compromiso y pensamiento crítico. Al usar la IA como herramienta en el proceso de aprendizaje, los estudiantes no solo se familiarizan con sus capacidades, sino que también desarrollan la capacidad de evaluar críticamente el contenido que genera. Este enfoque los alienta a reflexionar sobre el lenguaje, el significado y la interpretación mientras participan en el análisis de texto, la escritura creativa, la oratoria y la gamificación, todo dentro de un marco interactivo y culturalmente rico.

Descripción de la actividad: Desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre”

Objetivo:

Los estudiantes mejorarán su comprensión auditiva y su producción escrita en español analizando y recreando letras de canciones con la ayuda de ChatGPT. Si bien las instrucciones se presentan aquí en inglés, la actividad debe realizarse en el idioma de destino, ya sea que se enseñe el español u otro idioma.

Instrucciones:

1. Escuche y decodifique

- Divida la clase en grupos de 2-3 estudiantes.

- Elija una canción en español (por ejemplo, La Llorona por chavela vargas, Oye CÓMO VA por Tito Puente, Vivir mi Vida por Marc Anthony).

- Proporcione a cada grupo una versión incompleta de la letra con palabras faltantes.

- Los estudiantes escuchan la canción y completan los espacios en blanco.

2. Interpretar y discutir

- Dentro de sus grupos, los estudiantes analizan el significado de la canción.

- Discuten lo que creen que transmiten las letras, incluidas las emociones, los temas y cualquier referencia cultural que reconocan.

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- ¿Puedes identificar alguna referencia cultural en la canción? ¿Cómo dan forma a su significado?

- ¿Cómo influye la música (melodía, ritmo, etc.) en su interpretación de la letra?

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

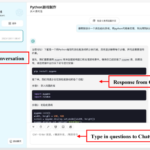

3. Comparar con chatgpt

- Después de formar su propio análisis, los estudiantes preguntan a Chatgpt:

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- Comparan la interpretación de ChatGPT con sus propias ideas y discuten similitudes o diferencias.

4. Crea tu propio verso

- Cada grupo escribe un nuevo verso que coincide con el estilo y el ritmo de la canción.

- Pueden pedirle ayuda a ChatGPT: “Ayúdanos a escribir un nuevo verso para esta canción con el mismo estilo”.

5. Realizar y cantar

- Cada grupo presenta su nuevo verso a la clase.

- Si se sienten cómodos, pueden cantarlo usando la melodía original.

- Es beneficioso que el profesor tenga una versión de karaoke (instrumental) de la canción disponible para que las letras de los estudiantes se puedan escuchar claramente.

- Mostrar las nuevas letras en un monitor o proyector permite que otros estudiantes sigan y canten juntos, mejorando la experiencia colectiva.

6. Elección – El Grammy va a

Los estudiantes votan por diferentes categorías, incluyendo:

- Mejor adaptación

- Mejor reflexión

- Mejor rendimiento

- Mejor actitud

- Mejor colaboración

7. Reflexión final

- ¿Cuál fue la parte más desafiante de comprender la letra?

- ¿Cómo ayudó ChatGPT a interpretar la canción?

- ¿Qué nuevas palabras o expresiones aprendiste?

Pensamientos finales: música, IA y pensamiento crítico

Un desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre” (Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt: “Cantar y Descubrir”) es una actividad que he encontrado que es especialmente efectiva en mis cursos intermedios y avanzados. Lo uso cuando los estudiantes se sienten abrumados o distraídos, a menudo alrededor de los exámenes parciales, como una forma de ayudarlos a relajarse y reconectarse con el material. Sirve como un descanso refrescante, lo que permite a los estudiantes alejarse del estrés de las tareas y reenfocarse de una manera divertida e interactiva. Al incorporar música, creatividad y tecnología, mantenemos a los estudiantes presentes en la clase, incluso cuando todo lo demás parece exigir su atención.

Más allá de ofrecer una pausa bien merecida, esta actividad provoca discusiones atractivas sobre la interpretación del lenguaje, el contexto cultural y el papel de la IA en la educación. A medida que los estudiantes comparan sus propias interpretaciones de las letras de las canciones con las generadas por ChatGPT, comienzan a reconocer tanto el valor como las limitaciones de la IA. Estas ideas fomentan el pensamiento crítico, ayudándoles a desarrollar un enfoque más maduro de la tecnología y su impacto en su aprendizaje.

Agregar el elemento de karaoke mejora aún más la experiencia, dando a los estudiantes la oportunidad de realizar sus nuevos versos y divertirse mientras practica sus habilidades lingüísticas. Mostrar la letra en una pantalla hace que la actividad sea más inclusiva, lo que permite a todos seguirlo. Para hacerlo aún más agradable, seleccionando canciones que resuenen con los gustos de los estudiantes, ya sea un clásico como La Llorona O un éxito contemporáneo de artistas como Bad Bunny, Selena, Daddy Yankee o Karol G, hace que la actividad se sienta más personal y atractiva.

Esta actividad no se limita solo al aula. Es una gran adición a los clubes españoles o eventos especiales, donde los estudiantes pueden unirse a un amor compartido por la música mientras practican sus habilidades lingüísticas. Después de todo, ¿quién no disfruta de una buena parodia de su canción favorita?

Mezclar el aprendizaje de idiomas con música y tecnología, Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt Crea un entorno dinámico e interactivo que revitaliza a los estudiantes y profundiza su conexión con el lenguaje y el papel evolutivo de la IA. Convierte los momentos de agotamiento en oportunidades de creatividad, exploración cultural y entusiasmo renovado por el aprendizaje.

Angela Rodríguez Mooney, PhD, es profesora asistente de español y la Universidad de Mujeres de Texas.

Referencias

Baghurst, Timothy y Betty C. Kelley. “Un examen del estrés en los estudiantes universitarios en el transcurso de un semestre”. Práctica de promoción de la salud 15, no. 3 (2014): 438-447.

DeGrave, Pauline. “Música en el aula de idiomas extranjeros: cómo y por qué”. Revista de Enseñanza e Investigación de Lenguas 10, no. 3 (2019): 412-420.

Felder, Richard M. y Eunice R. Henriques. “Estilos de aprendizaje y enseñanza en la educación extranjera y de segundo idioma”. Anales de idiomas extranjeros 28, no. 1 (1995): 21-31.

Nuessel, Frank y April D. Marshall. “Prácticas y principios para involucrar a los tres modos comunicativos en español a través de canciones y música”. Hispania (2008): 139-146.

Kumar, Tribhuwan, Shamim Akhter, Mehrunnisa M. Yunus y Atefeh Shamsy. “Uso de la música y las canciones como herramientas pedagógicas en la enseñanza del inglés como contextos de idiomas extranjeros”. Education Research International 2022, no. 1 (2022): 1-9

Noticias

5 indicaciones de chatgpt que pueden ayudar a los adolescentes a lanzar una startup

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Teen emprendedor que usa chatgpt para ayudarlo con su negocio

El emprendimiento adolescente sigue en aumento. Según Junior Achievement Research, el 66% de los adolescentes estadounidenses de entre 13 y 17 años dicen que es probable que considere comenzar un negocio como adultos, con el monitor de emprendimiento global 2023-2024 que encuentra que el 24% de los jóvenes de 18 a 24 años son actualmente empresarios. Estos jóvenes fundadores no son solo soñando, están construyendo empresas reales que generan ingresos y crean un impacto social, y están utilizando las indicaciones de ChatGPT para ayudarlos.

En Wit (lo que sea necesario), la organización que fundó en 2009, hemos trabajado con más de 10,000 jóvenes empresarios. Durante el año pasado, he observado un cambio en cómo los adolescentes abordan la planificación comercial. Con nuestra orientación, están utilizando herramientas de IA como ChatGPT, no como atajos, sino como socios de pensamiento estratégico para aclarar ideas, probar conceptos y acelerar la ejecución.

Los emprendedores adolescentes más exitosos han descubierto indicaciones específicas que los ayudan a pasar de una idea a otra. Estas no son sesiones genéricas de lluvia de ideas: están utilizando preguntas específicas que abordan los desafíos únicos que enfrentan los jóvenes fundadores: recursos limitados, compromisos escolares y la necesidad de demostrar sus conceptos rápidamente.

Aquí hay cinco indicaciones de ChatGPT que ayudan constantemente a los emprendedores adolescentes a construir negocios que importan.

1. El problema del primer descubrimiento chatgpt aviso

“Me doy cuenta de que [specific group of people]

luchar contra [specific problem I’ve observed]. Ayúdame a entender mejor este problema explicando: 1) por qué existe este problema, 2) qué soluciones existen actualmente y por qué son insuficientes, 3) cuánto las personas podrían pagar para resolver esto, y 4) tres formas específicas en que podría probar si este es un problema real que vale la pena resolver “.

Un adolescente podría usar este aviso después de notar que los estudiantes en la escuela luchan por pagar el almuerzo. En lugar de asumir que entienden el alcance completo, podrían pedirle a ChatGPT que investigue la deuda del almuerzo escolar como un problema sistémico. Esta investigación puede llevarlos a crear un negocio basado en productos donde los ingresos ayuden a pagar la deuda del almuerzo, lo que combina ganancias con el propósito.

Los adolescentes notan problemas de manera diferente a los adultos porque experimentan frustraciones únicas, desde los desafíos de las organizaciones escolares hasta las redes sociales hasta las preocupaciones ambientales. Según la investigación de Square sobre empresarios de la Generación de la Generación Z, el 84% planea ser dueños de negocios dentro de cinco años, lo que los convierte en candidatos ideales para las empresas de resolución de problemas.

2. El aviso de chatgpt de chatgpt de chatgpt de realidad de la realidad del recurso

“Soy [age] años con aproximadamente [dollar amount] invertir y [number] Horas por semana disponibles entre la escuela y otros compromisos. Según estas limitaciones, ¿cuáles son tres modelos de negocio que podría lanzar de manera realista este verano? Para cada opción, incluya costos de inicio, requisitos de tiempo y los primeros tres pasos para comenzar “.

Este aviso se dirige al elefante en la sala: la mayoría de los empresarios adolescentes tienen dinero y tiempo limitados. Cuando un empresario de 16 años emplea este enfoque para evaluar un concepto de negocio de tarjetas de felicitación, puede descubrir que pueden comenzar con $ 200 y escalar gradualmente. Al ser realistas sobre las limitaciones por adelantado, evitan el exceso de compromiso y pueden construir hacia objetivos de ingresos sostenibles.

Según el informe de Gen Z de Square, el 45% de los jóvenes empresarios usan sus ahorros para iniciar negocios, con el 80% de lanzamiento en línea o con un componente móvil. Estos datos respaldan la efectividad de la planificación basada en restricciones: cuando funcionan los adolescentes dentro de las limitaciones realistas, crean modelos comerciales más sostenibles.

3. El aviso de chatgpt del simulador de voz del cliente

“Actúa como un [specific demographic] Y dame comentarios honestos sobre esta idea de negocio: [describe your concept]. ¿Qué te excitaría de esto? ¿Qué preocupaciones tendrías? ¿Cuánto pagarías de manera realista? ¿Qué necesitaría cambiar para que se convierta en un cliente? “

Los empresarios adolescentes a menudo luchan con la investigación de los clientes porque no pueden encuestar fácilmente a grandes grupos o contratar firmas de investigación de mercado. Este aviso ayuda a simular los comentarios de los clientes haciendo que ChatGPT adopte personas específicas.

Un adolescente que desarrolla un podcast para atletas adolescentes podría usar este enfoque pidiéndole a ChatGPT que responda a diferentes tipos de atletas adolescentes. Esto ayuda a identificar temas de contenido que resuenan y mensajes que se sienten auténticos para el público objetivo.

El aviso funciona mejor cuando se vuelve específico sobre la demografía, los puntos débiles y los contextos. “Actúa como un estudiante de último año de secundaria que solicita a la universidad” produce mejores ideas que “actuar como un adolescente”.

4. El mensaje mínimo de diseñador de prueba viable chatgpt

“Quiero probar esta idea de negocio: [describe concept] sin gastar más de [budget amount] o más de [time commitment]. Diseñe tres experimentos simples que podría ejecutar esta semana para validar la demanda de los clientes. Para cada prueba, explique lo que aprendería, cómo medir el éxito y qué resultados indicarían que debería avanzar “.

Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a adoptar la metodología Lean Startup sin perderse en la jerga comercial. El enfoque en “This Week” crea urgencia y evita la planificación interminable sin acción.

Un adolescente que desea probar un concepto de línea de ropa podría usar este indicador para diseñar experimentos de validación simples, como publicar maquetas de diseño en las redes sociales para evaluar el interés, crear un formulario de Google para recolectar pedidos anticipados y pedirles a los amigos que compartan el concepto con sus redes. Estas pruebas no cuestan nada más que proporcionar datos cruciales sobre la demanda y los precios.

5. El aviso de chatgpt del generador de claridad de tono

“Convierta esta idea de negocio en una clara explicación de 60 segundos: [describe your business]. La explicación debe incluir: el problema que resuelve, su solución, a quién ayuda, por qué lo elegirían sobre las alternativas y cómo se ve el éxito. Escríbelo en lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría “.

La comunicación clara separa a los empresarios exitosos de aquellos con buenas ideas pero una ejecución deficiente. Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a destilar conceptos complejos a explicaciones convincentes que pueden usar en todas partes, desde las publicaciones en las redes sociales hasta las conversaciones con posibles mentores.

El énfasis en el “lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría” es importante. Muchas plantillas de lanzamiento comercial suenan artificiales cuando se entregan jóvenes fundadores. La autenticidad es más importante que la jerga corporativa.

Más allá de las indicaciones de chatgpt: estrategia de implementación

La diferencia entre los adolescentes que usan estas indicaciones de manera efectiva y aquellos que no se reducen a seguir. ChatGPT proporciona dirección, pero la acción crea resultados.

Los jóvenes empresarios más exitosos con los que trabajo usan estas indicaciones como puntos de partida, no de punto final. Toman las sugerencias generadas por IA e inmediatamente las prueban en el mundo real. Llaman a clientes potenciales, crean prototipos simples e iteran en función de los comentarios reales.

Investigaciones recientes de Junior Achievement muestran que el 69% de los adolescentes tienen ideas de negocios, pero se sienten inciertos sobre el proceso de partida, con el miedo a que el fracaso sea la principal preocupación para el 67% de los posibles empresarios adolescentes. Estas indicaciones abordan esa incertidumbre al desactivar los conceptos abstractos en los próximos pasos concretos.

La imagen más grande

Los emprendedores adolescentes que utilizan herramientas de IA como ChatGPT representan un cambio en cómo está ocurriendo la educación empresarial. Según la investigación mundial de monitores empresariales, los jóvenes empresarios tienen 1,6 veces más probabilidades que los adultos de querer comenzar un negocio, y son particularmente activos en la tecnología, la alimentación y las bebidas, la moda y los sectores de entretenimiento. En lugar de esperar clases de emprendimiento formales o programas de MBA, estos jóvenes fundadores están accediendo a herramientas de pensamiento estratégico de inmediato.

Esta tendencia se alinea con cambios más amplios en la educación y la fuerza laboral. El Foro Económico Mundial identifica la creatividad, el pensamiento crítico y la resiliencia como las principales habilidades para 2025, la capacidad de las capacidades que el espíritu empresarial desarrolla naturalmente.

Programas como WIT brindan soporte estructurado para este viaje, pero las herramientas en sí mismas se están volviendo cada vez más accesibles. Un adolescente con acceso a Internet ahora puede acceder a recursos de planificación empresarial que anteriormente estaban disponibles solo para empresarios establecidos con presupuestos significativos.

La clave es usar estas herramientas cuidadosamente. ChatGPT puede acelerar el pensamiento y proporcionar marcos, pero no puede reemplazar el arduo trabajo de construir relaciones, crear productos y servir a los clientes. La mejor idea de negocio no es la más original, es la que resuelve un problema real para personas reales. Las herramientas de IA pueden ayudar a identificar esas oportunidades, pero solo la acción puede convertirlos en empresas que importan.

Noticias

Chatgpt vs. gemini: he probado ambos, y uno definitivamente es mejor

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Precio

ChatGPT y Gemini tienen versiones gratuitas que limitan su acceso a características y modelos. Los planes premium para ambos también comienzan en alrededor de $ 20 por mes. Las características de chatbot, como investigaciones profundas, generación de imágenes y videos, búsqueda web y más, son similares en ChatGPT y Gemini. Sin embargo, los planes de Gemini pagados también incluyen el almacenamiento en la nube de Google Drive (a partir de 2TB) y un conjunto robusto de integraciones en las aplicaciones de Google Workspace.

Los niveles de más alta gama de ChatGPT y Gemini desbloquean el aumento de los límites de uso y algunas características únicas, pero el costo mensual prohibitivo de estos planes (como $ 200 para Chatgpt Pro o $ 250 para Gemini Ai Ultra) los pone fuera del alcance de la mayoría de las personas. Las características específicas del plan Pro de ChatGPT, como el modo O1 Pro que aprovecha el poder de cálculo adicional para preguntas particularmente complicadas, no son especialmente relevantes para el consumidor promedio, por lo que no sentirá que se está perdiendo. Sin embargo, es probable que desee las características que son exclusivas del plan Ai Ultra de Gemini, como la generación de videos VEO 3.

Ganador: Géminis

Plataformas

Puede acceder a ChatGPT y Gemini en la web o a través de aplicaciones móviles (Android e iOS). ChatGPT también tiene aplicaciones de escritorio (macOS y Windows) y una extensión oficial para Google Chrome. Gemini no tiene aplicaciones de escritorio dedicadas o una extensión de Chrome, aunque se integra directamente con el navegador.

(Crédito: OpenAI/PCMAG)

Chatgpt está disponible en otros lugares, Como a través de Siri. Como se mencionó, puede acceder a Gemini en las aplicaciones de Google, como el calendario, Documento, ConducirGmail, Mapas, Mantener, FotosSábanas, y Música de YouTube. Tanto los modelos de Chatgpt como Gemini también aparecen en sitios como la perplejidad. Sin embargo, obtiene la mayor cantidad de funciones de estos chatbots en sus aplicaciones y portales web dedicados.

Las interfaces de ambos chatbots son en gran medida consistentes en todas las plataformas. Son fáciles de usar y no lo abruman con opciones y alternar. ChatGPT tiene algunas configuraciones más para jugar, como la capacidad de ajustar su personalidad, mientras que la profunda interfaz de investigación de Gemini hace un mejor uso de los bienes inmuebles de pantalla.

Ganador: empate

Modelos de IA

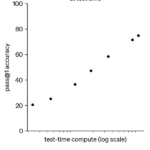

ChatGPT tiene dos series primarias de modelos, la serie 4 (su línea de conversación, insignia) y la Serie O (su compleja línea de razonamiento). Gemini ofrece de manera similar una serie Flash de uso general y una serie Pro para tareas más complicadas.

Los últimos modelos de Chatgpt son O3 y O4-Mini, y los últimos de Gemini son 2.5 Flash y 2.5 Pro. Fuera de la codificación o la resolución de una ecuación, pasará la mayor parte de su tiempo usando los modelos de la serie 4-Series y Flash. A continuación, puede ver cómo funcionan estos modelos en una variedad de tareas. Qué modelo es mejor depende realmente de lo que quieras hacer.

Ganador: empate

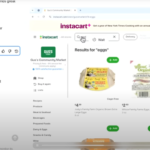

Búsqueda web

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden buscar información actualizada en la web con facilidad. Sin embargo, ChatGPT presenta mosaicos de artículos en la parte inferior de sus respuestas para una lectura adicional, tiene un excelente abastecimiento que facilita la vinculación de reclamos con evidencia, incluye imágenes en las respuestas cuando es relevante y, a menudo, proporciona más detalles en respuesta. Gemini no muestra nombres de fuente y títulos de artículos completos, e incluye mosaicos e imágenes de artículos solo cuando usa el modo AI de Google. El abastecimiento en este modo es aún menos robusto; Google relega las fuentes a los caretes que se pueden hacer clic que no resaltan las partes relevantes de su respuesta.

Como parte de sus experiencias de búsqueda en la web, ChatGPT y Gemini pueden ayudarlo a comprar. Si solicita consejos de compra, ambos presentan mosaicos haciendo clic en enlaces a los minoristas. Sin embargo, Gemini generalmente sugiere mejores productos y tiene una característica única en la que puede cargar una imagen tuya para probar digitalmente la ropa antes de comprar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Investigación profunda

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden generar informes que tienen docenas de páginas e incluyen más de 50 fuentes sobre cualquier tema. La mayor diferencia entre los dos se reduce al abastecimiento. Gemini a menudo cita más fuentes que CHATGPT, pero maneja el abastecimiento en informes de investigación profunda de la misma manera que lo hace en la búsqueda en modo AI, lo que significa caretas que se puede hacer clic sin destacados en el texto. Debido a que es más difícil conectar las afirmaciones en los informes de Géminis a fuentes reales, es más difícil creerles. El abastecimiento claro de ChatGPT con destacados en el texto es más fácil de confiar. Sin embargo, Gemini tiene algunas características de calidad de vida en ChatGPT, como la capacidad de exportar informes formateados correctamente a Google Docs con un solo clic. Su tono también es diferente. Los informes de ChatGPT se leen como publicaciones de foro elaboradas, mientras que los informes de Gemini se leen como documentos académicos.

Ganador: chatgpt

Generación de imágenes

La generación de imágenes de ChatGPT impresiona independientemente de lo que solicite, incluso las indicaciones complejas para paneles o diagramas cómicos. No es perfecto, pero los errores y la distorsión son mínimos. Gemini genera imágenes visualmente atractivas más rápido que ChatGPT, pero rutinariamente incluyen errores y distorsión notables. Con indicaciones complicadas, especialmente diagramas, Gemini produjo resultados sin sentido en las pruebas.

Arriba, puede ver cómo ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Géminis (segunda diapositiva) les fue con el siguiente mensaje: “Genere una imagen de un estudio de moda con una decoración simple y rústica que contrasta con el espacio más agradable. Incluya un sofá marrón y paredes de ladrillo”. La imagen de ChatGPT limita los problemas al detalle fino en las hojas de sus plantas y texto en su libro, mientras que la imagen de Gemini muestra problemas más notables en su tubo de cordón y lámpara.

Ganador: chatgpt

¡Obtenga nuestras mejores historias!

Toda la última tecnología, probada por nuestros expertos

Regístrese en el boletín de informes de laboratorio para recibir las últimas revisiones de productos de PCMAG, comprar asesoramiento e ideas.

Al hacer clic en Registrarme, confirma que tiene más de 16 años y acepta nuestros Términos de uso y Política de privacidad.

¡Gracias por registrarse!

Su suscripción ha sido confirmada. ¡Esté atento a su bandeja de entrada!

Generación de videos

La generación de videos de Gemini es la mejor de su clase, especialmente porque ChatGPT no puede igualar su capacidad para producir audio acompañante. Actualmente, Google bloquea el último modelo de generación de videos de Gemini, VEO 3, detrás del costoso plan AI Ultra, pero obtienes más videos realistas que con ChatGPT. Gemini también tiene otras características que ChatGPT no, como la herramienta Flow Filmmaker, que le permite extender los clips generados y el animador AI Whisk, que le permite animar imágenes fijas. Sin embargo, tenga en cuenta que incluso con VEO 3, aún necesita generar videos varias veces para obtener un gran resultado.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité a ChatGPT y Gemini a mostrarme un solucionador de cubos de Rubik Rubik que resuelva un cubo. La persona en el video de Géminis se ve muy bien, y el audio acompañante es competente. Al final, hay una buena atención al detalle con el marco que se desplaza, simulando la detención de una grabación de selfies. Mientras tanto, Chatgpt luchó con su cubo, distorsionándolo en gran medida.

Ganador: Géminis

Procesamiento de archivos

Comprender los archivos es una fortaleza de ChatGPT y Gemini. Ya sea que desee que respondan preguntas sobre un manual, editen un currículum o le informen algo sobre una imagen, ninguno decepciona. Sin embargo, ChatGPT tiene la ventaja sobre Gemini, ya que ofrece un reconocimiento de imagen ligeramente mejor y respuestas más detalladas cuando pregunta sobre los archivos cargados. Ambos chatbots todavía a veces inventan citas de documentos proporcionados o malinterpretan las imágenes, así que asegúrese de verificar sus resultados.

Ganador: chatgpt

Escritura creativa

Chatgpt y Gemini pueden generar poemas, obras, historias y más competentes. CHATGPT, sin embargo, se destaca entre los dos debido a cuán únicas son sus respuestas y qué tan bien responde a las indicaciones. Las respuestas de Gemini pueden sentirse repetitivas si no calibra cuidadosamente sus solicitudes, y no siempre sigue todas las instrucciones a la carta.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Gemini (segunda diapositiva) con lo siguiente: “Sin hacer referencia a nada en su memoria o respuestas anteriores, quiero que me escriba un poema de verso gratuito. Preste atención especial a la capitalización, enjambment, ruptura de línea y puntuación. Dado que es un verso libre, no quiero un medidor familiar o un esquema de retiro de la rima, pero quiero que tenga un estilo de coohes. ChatGPT logró entregar lo que pedí en el aviso, y eso era distinto de las generaciones anteriores. Gemini tuvo problemas para generar un poema que incorporó cualquier cosa más allá de las comas y los períodos, y su poema anterior se lee de manera muy similar a un poema que generó antes.

Recomendado por nuestros editores

Ganador: chatgpt

Razonamiento complejo

Los modelos de razonamiento complejos de Chatgpt y Gemini pueden manejar preguntas de informática, matemáticas y física con facilidad, así como mostrar de manera competente su trabajo. En las pruebas, ChatGPT dio respuestas correctas un poco más a menudo que Gemini, pero su rendimiento es bastante similar. Ambos chatbots pueden y le darán respuestas incorrectas, por lo que verificar su trabajo aún es vital si está haciendo algo importante o tratando de aprender un concepto.

Ganador: chatgpt

Integración

ChatGPT no tiene integraciones significativas, mientras que las integraciones de Gemini son una característica definitoria. Ya sea que desee obtener ayuda para editar un ensayo en Google Docs, comparta una pestaña Chrome para hacer una pregunta, pruebe una nueva lista de reproducción de música de YouTube personalizada para su gusto o desbloquee ideas personales en Gmail, Gemini puede hacer todo y mucho más. Es difícil subestimar cuán integrales y poderosas son realmente las integraciones de Géminis.

Ganador: Géminis

Asistentes de IA

ChatGPT tiene GPT personalizados, y Gemini tiene gemas. Ambos son asistentes de IA personalizables. Tampoco es una gran actualización sobre hablar directamente con los chatbots, pero los GPT personalizados de terceros agregan una nueva funcionalidad, como el fácil acceso a Canva para editar imágenes generadas. Mientras tanto, terceros no pueden crear gemas, y no puedes compartirlas. Puede permitir que los GPT personalizados accedan a la información externa o tomen acciones externas, pero las GEM no tienen una funcionalidad similar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Contexto Windows y límites de uso

La ventana de contexto de ChatGPT sube a 128,000 tokens en sus planes de nivel superior, y todos los planes tienen límites de uso dinámicos basados en la carga del servidor. Géminis, por otro lado, tiene una ventana de contexto de 1,000,000 token. Google no está demasiado claro en los límites de uso exactos para Gemini, pero también son dinámicos dependiendo de la carga del servidor. Anecdóticamente, no pude alcanzar los límites de uso usando los planes pagados de Chatgpt o Gemini, pero es mucho más fácil hacerlo con los planes gratuitos.

Ganador: Géminis

Privacidad

La privacidad en Chatgpt y Gemini es una bolsa mixta. Ambos recopilan cantidades significativas de datos, incluidos todos sus chats, y usan esos datos para capacitar a sus modelos de IA de forma predeterminada. Sin embargo, ambos le dan la opción de apagar el entrenamiento. Google al menos no recopila y usa datos de Gemini para fines de capacitación en aplicaciones de espacio de trabajo, como Gmail, de forma predeterminada. ChatGPT y Gemini también prometen no vender sus datos o usarlos para la orientación de anuncios, pero Google y OpenAI tienen historias sórdidas cuando se trata de hacks, filtraciones y diversos fechorías digitales, por lo que recomiendo no compartir nada demasiado sensible.

Ganador: empate

Related posts

Trending

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoRemove.bg: La Revolución en la Edición de Imágenes que Debes Conocer

-

Tutoriales2 años ago

Tutoriales2 años agoCómo Comenzar a Utilizar ChatGPT: Una Guía Completa para Principiantes

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoStartups de IA en EE.UU. que han recaudado más de $100M en 2024

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoDeepgram: Revolucionando el Reconocimiento de Voz con IA

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoCómo Empezar con Popai.pro: Tu Espacio Personal de IA – Guía Completa, Instalación, Versiones y Precios

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoPerplexity aplicado al Marketing Digital y Estrategias SEO

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial Aplicada de 4Geeks Academy 2024

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial de UC Berkeley estratégico para negocios