Noticias

ChatGPT vs the Honor Code

Published

1 año agoon

Two of them were sprawled out on a long concrete bench in front of the main Haverford College library, one scribbling in a battered spiral-ring notebook, the other making annotations in the white margins of a novel. Three more sat on the ground beneath them, crisscross-applesauce, chatting about classes. A little hip, a little nerdy, a little tattooed; unmistakably English majors. The scene had the trappings of a campus-movie set piece: blue skies, green greens, kids both working and not working, at once anxious and carefree.

I said I was sorry to interrupt them, and they were kind enough to pretend that I hadn’t. I explained that I’m a writer, interested in how artificial intelligence is affecting higher education, particularly the humanities. When I asked whether they felt that ChatGPT-assisted cheating was common on campus, they looked at me like I had three heads. “I’m an English major,” one told me. “I want to write.” Another added: “Chat doesn’t write well anyway. It sucks.” A third chimed in, “What’s the point of being an English major if you don’t want to write?” They all murmured in agreement.

What’s the point, indeed? The conventional wisdom is that the American public has lost faith in the humanities—and lost both competence and interest in reading and writing, possibly heralding a post-literacy age. And since the emergence of ChatGPT, which is capable of producing long-form responses to short prompts, colleges and universities have tried, rather unsuccessfully, to stamp out the use of what has become the ultimate piece of cheating technology, resulting in a mix of panic and resignation about the impact AI will have on education. But at Haverford, by contrast, the story seemed different. Walking onto campus was like stepping into a time machine, and not only because I had graduated from the school a decade earlier. The tiny, historically Quaker college on Philadelphia’s Main Line still maintains its old honor code, and students still seem to follow it instead of letting a large language model do their thinking for them. For the most part, the students and professors I talked with seemed totally unfazed by this supposedly threatening new technology.

Read: The best way to prevent cheating in college

The two days I spent at Haverford and nearby Bryn Mawr College, in addition to interviews with people at other colleges with honor codes, left me convinced that the main question about AI in higher education has little to do with what kind of academic assignments the technology is or is not capable of replacing. The challenge posed by ChatGPT for American colleges and universities is not primarily technological but cultural and economic.

It is cultural because stemming the use of Chat—as nearly every student I interviewed referred to ChatGPT—requires an atmosphere in which a credible case is made, on a daily basis, that writing and reading have a value that transcends the vagaries of this or that particular assignment or résumé line item or career milestone. And it is economic because this cultural infrastructure isn’t free: Academic honor and intellectual curiosity do not spring from some inner well of rectitude we call “character,” or at least they do not spring only from that. Honor and curiosity can be nurtured, or crushed, by circumstance.

Rich private colleges with honor codes do not have a monopoly on academic integrity—millions of students and faculty at cash-strapped public universities around the country are also doing their part to keep the humanities alive in the face of generative AI. But at the wealthy schools that have managed to keep AI at bay, institutional resources play a central role in their success. The structures that make Haverford’s honor code function—readily available writing support, small classes, and comparatively unharried faculty—are likely not scalable in a higher-education landscape characterized by yawning inequalities, collapsing tenure-track employment, and the razing of public education at both the primary and secondary levels.

When OpenAI’s ChatGPT launched on November 30, 2022, colleges and universities were returning from Thanksgiving break. Professors were caught flat-footed as students quickly began using the generative-AI wonder app to cut corners on assignments, or to write them outright. Within a few weeks of the program’s release, ChatGPT was heralded as bringing about “the end of high-school English” and the death of the college essay. These early predictions were hyperbolic, but only just. As The Atlantic’s Ian Bogost recently argued, there has been effectively zero progress in stymying AI cheating in the years since. One professor summarized the views of many in a recent mega-viral X post: “I am no longer a teacher. I’m just a human plagiarism detector. I used to spend my grading time giving comments for improving writing skills. Now most of that time is just checking to see if a student wrote their own paper.”

While some institutions and faculty have bristled at the encroachment of AI, others have simply thrown in the towel, insisting that we need to treat large language models like “tools” to be “integrated” into the classroom.

I’ve felt uneasy about the tacit assumption that ChatGPT plagiarism is inevitable, that it is human nature to seek technological shortcuts. In my experience as a student at Haverford and then a professor at a small liberal-arts college in Maine, most students genuinely do want to learn and generally aren’t eager to outsource their thinking and writing to a machine. Although I had my own worries about AI, I was also not sold on the idea that it’s impossible to foster a community in which students resist ChatGPT in favor of actually doing the work. I returned to Haverford last month to see whether my fragile optimism was warranted.

When I stopped a professor walking toward the college’s nature trail to ask if ChatGPT was an issue at Haverford, she appeared surprised by the question: “I’m probably not the right person to ask. That’s a question for students, isn’t it?” Several other faculty members I spoke with said they didn’t think much about ChatGPT and cheating, and repeated variations of the phrase I’m not the police.

Haverford’s academic climate is in part a product of its cultural and religious history. During my four years at the school, invocations of “Quaker values” were constant, emphasizing on personal responsibility, humility, and trust in other members of the community. Discussing grades was taboo because it invited competition and distracted from the intrinsic value of learning.

The honor code is the most concrete expression of Haverford’s Quaker ethos. Students are trusted to take tests without proctors and even to bring exams back to their dorm rooms. Matthew Feliz, a fellow Haverford alum who is now a visiting art-history professor at Bryn Mawr—a school also governed by an honor code—put it this way: “The honor code is a kind of contract. And that contract gives students the benefit of the doubt. That’s the place we always start from: giving students the benefit of the doubt.”

Read: The first year of AI college ends in ruin

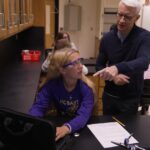

Darin Hayton, a historian of science at the college, seemed to embody this untroubled attitude. Reclining in his office chair, surrounded by warm wood and, for 270 degrees, well-loved books, he said of ChatGPT, “I just don’t give a shit about it.” He explained that his teaching philosophy is predicated on modeling the merits of a life of deep thinking, reading, and writing. “I try to show students the value of what historians do. I hope they’re interested, but if they’re not, that’s okay too.” He relies on creating an atmosphere in which students want to do their work, and at Haverford, he said, they mostly do. Hayton was friendly, animated, and radiated a kind of effortless intelligence. I found myself, quite literally, leaning forward when he spoke. It was not hard to believe that his students did the same.

“It seems to me that this anxiety in our profession over ChatGPT isn’t ultimately about cheating.” Kim Benston, a literary historian at Haverford and a former president of the college, told me. “It’s an existential anxiety that reflects a deeper concern about the future of the humanities,” he continued. Another humanities professor echoed these remarks, saying that he didn’t personally worry about ChatGPT but agreed that the professorial concern about AI was, at bottom, a fear of becoming irrelevant: “We are in the sentence-making business. And it looks like they don’t need us to make sentences any more.”

I told Benston that I had struggled with whether to continue assigning traditional essays—and risk the possibility of students using ChatGPT—or resort to using in-class, pen-and-paper exams. I’d decided that literature classes without longer, take-home essays are not literature classes. He nodded. The impulse to surveil students, to view all course activity through a paranoid lens, and to resort to cheating-proof assignments was not only about the students or their work, he suggested. These measures were also about nervous humanities professors proving to themselves that they’re still necessary.

My conversations with students convinced me that Hayston, Benston, and their colleagues’ build-it-and-they-will-come sentiment, hopelessly naive though it may seem, was largely correct. Of the dozens of Haverford students I talked with, not a single one said they thought AI cheating was a substantial problem at the school. These interviews were so repetitive, they almost became boring.

The jock sporting bright bruises from some kind of contact sport? “Haverford students don’t really cheat.” The econ major in prepster shorts and a Jackson Hole T-shirt? “Students follow the honor code.” A bubbly first-year popping out of a dorm? “So far I haven’t heard of anyone using ChatGPT. At my high school it was everywhere!” More than a few students seemed off put by the very suggestion that a Haverfordian might cheat. “There is a lot of freedom here and a lot of student autonomy,” a sophomore psychology major told me. “This is a place where you could get away with it if you wanted to. And because of that, I think students are very careful not to abuse that freedom.” The closest I got to a dissenting voice was a contemplative senior who mused: “The honor code is definitely working for now. It may not be working two years from now as ChatGPT gets better. But for now there’s still a lot of trust between students and faculty.”

To be sure, despite that trust, Haverford does have occasional issues with ChatGPT. A student who serves on Haverford’s honor council, which is responsible for handling academic-integrity cases, told me, “There’s generally not too much cheating at Haverford, but it happens.” He said that the primary challenge is that “ChatGPT makes it easy to lie,” meaning the honor council struggles to definitively prove that a student who is suspected of cheating used AI. Still, both he and a fellow member of the council agreed that Haverford seems to have far fewer issues with LLM cheating than peer institutions. Only a single AI case came before the honor council over the past year.

In another sign that LLMs may be preoccupying some people at the college, one survey of the literature and language faculty found that most teachers in these fields banned AI outright, according to the librarian who distributed the query. A number of professors also mentioned that a provost had recently sent out an email survey about AI use on campus. But in keeping with the general disinterest in ChatGPT I encountered at Haverford, no one I talked with seemed to have paid much attention to the email.

Wandering over to Bryn Mawr in search of new perspectives, I found a similar story. A Classics professor I bumped into by a bus stop told me, “I try not to be suspicious of students. ChatGPT isn’t something I spend time worrying about. I think if they use ChatGPT, they’re robbing themselves of an opportunity.” When I smiled, perhaps a little too knowingly, he added: “Of course a professor would say that, but I think our students really believe that too.” Bryn Mawr students seemed to take the honor code every bit as seriously as that professor believed they would, perhaps none more passionately than a pair of transfer students I came across, posted up under one of the college’s gothic stone archways.

“The adherence to it to me has been shocking,” a senior who transferred from the University of Pittsburgh said of the honor code. “I can’t believe how many people don’t just cheat. It feels not that hard to [cheat] because there’s so much faith in students.” She explained her theory of why Bryn Mawr’s honor code hadn’t been challenged by ChatGPT: “Prior to the proliferation of AI it was already easy to cheat, and they didn’t, and so I think they continue not to.” Her friend, a transfer from another large state university, agreed. “I also think it’s a point of pride,” she observed. “People take pride in their work here, whereas students at my previous school were only there to get their degree and get out.”

The testimony of these transfer students most effectively made the case that schools with strong honor codes really are different. But the contrast the students pointed to—comparatively affordable public schools where AI cheating is ubiquitous, gilded private schools where it is not—also hinted at a reality that troubles whatever moralistic spin we might want to put on the apparent success of Haverford and Bryn Mawr. Positioning honor codes as a bulwark against academic misconduct in a post-AI world is too easy: You have to also acknowledge that schools like Haverford have dismantled—through the prodigious resources of the institution and its customers—many incentives to cheat.

It is one thing to eschew ChatGPT when your professors are available for office hours, and on-campus therapists can counsel you if you’re stressed out by an assignment, and tutors are ready to lend a hand if writer’s block strikes or confusion sets in, and one of your parents’ doctor friends is happy to write you an Adderall prescription if all else fails. It is another to eschew ChatGPT when you’re a single mother trying to squeeze in homework between shifts, or a non-native English speaker who has nowhere else to turn for a grammar check. Sarah Eaton, an expert on cheating and plagiarism at Canada’s University of Calgary, didn’t mince words: She called ChatGPT “a poor person’s tutor.” Indeed, several Haverford students mentioned that, although the honor code kept students from cheating, so too did the well-staffed writing center. “The writing center is more useful than ChatGPT anyway,” one said. “If I need help, I go there.”

But while these kinds of institutional resources matter, they’re also not the whole story. The decisive factor seems to be whether a university’s honor code is deeply woven into the fabric of campus life, or is little more than a policy slapped on a website. Tricia Bertram Gallant, an expert on cheating and a co-author of a forthcoming book on academic integrity, argues that honor codes are effective when they are “regularly made salient.” Two professors I spoke with at public universities that have strong honor codes emphasized this point. Thomas Crawford at Georgia Tech told me, “Honor codes are a two-way street—students are expected to be honest and produce their own work, but for the system to function, the faculty must trust those same students.” John Casteen, a former president and current English professor at the University of Virginia, said, “We don’t build suspicion into our educational model.” He acknowledged that there will always be some cheaters in any system, but in his experience UVA’s honor-code culture “keeps most students honest, most of the time.”

And if money and institutional resources are part of what makes honor codes work, recent developments at other schools also show that money can’t buy culture. Last spring, owing to increased cheating, Stanford’s governing bodies moved to end more than a century of unproctored exams, using what some called a “nuclear option” to override a student-government vote against the decision. A campus survey at Middlebury this year found that 65 percent of the students who responded said they’d broken the honor code, leading to a report that asserted, “The Honor Code has ceased to be a meaningful element of learning and living at Middlebury for most students.” An article by the school newspaper’s editorial board shared this assessment: “The Honor Code as it currently stands clearly does not effectively deter students from cheating. Nor does it inspire commitment to the ideals it is meant to represent such as integrity and trust.” Whether schools like Haverford can continue to resist these trends remains to be seen.

Last month, Fredric Jameson, arguably America’s preeminent living literary critic, passed away. His interests spanned, as a lengthy New York Times obituary noted, architecture, German opera, and sci-fi. An alumnus of Haverford, he was perhaps the greatest reader and writer the school ever produced.

Read: The decade in which everything was great but felt terrible

If Jameson was a singular talent, he was also the product of a singular historical moment in American education. He came up at a time when funding for humanities research was robust, tenure-track employment was relatively available, and the humanities were broadly popular with students and the public. His first major work of criticism, Marxism and Form, was published in 1971, a year that marked the high point of the English major: 7.6 percent of all students graduating from four-year American colleges and universities majored in English. Half a century later, that number cratered to 2.8 percent, humanities research funding slowed, and tenure-line employment in the humanities all but imploded.

Our higher-education system may not be capable of producing or supporting Fredric Jamesons any longer, and in a sense it is hard to blame students for resorting to ChatGPT. Who is telling them that reading and writing matter? America’s universities all too often treat teaching history, philosophy, and literature as part-time jobs, reducing professors to the scholarly equivalent of Uber drivers in an academic gig economy. America’s politicians, who fund public education, seem to see the humanities as an economically unproductive diversion for hobbyists at best, a menace to society at worst.

Haverford is a place where old forms of life, with all their wonder, are preserved for those privileged enough to visit, persisting in the midst of a broader world from which those same forms of life are disappearing. This trend did not start with OpenAI in November 2022, but it is being accelerated by the advent of magic machines that automate—imperfectly, for now—both reading and writing.

At the end of my trip, before heading to the airport, I walked to the Wawa, a 15-minute trek familiar to any self-respecting Haverford student, in search of a convenience-store sub and a bad coffee. On my way, I passed by the duck pond. On an out-of-the-way bench overlooking the water feature, in the shadow of a tree well older than she was, a student was sitting, her brimming backpack on the grass. There was a curl of smoke issued from a cigarette, or something slightly stronger, and a thick book open on her lap, face bent so close to the page her nose was almost touching it. With her free hand a finger traced the words, line by line, as she read.

You may like

Noticias

Revivir el compromiso en el aula de español: un desafío musical con chatgpt – enfoque de la facultad

Published

8 meses agoon

6 junio, 2025

A mitad del semestre, no es raro notar un cambio en los niveles de energía de sus alumnos (Baghurst y Kelley, 2013; Kumari et al., 2021). El entusiasmo inicial por aprender un idioma extranjero puede disminuir a medida que otros cursos con tareas exigentes compitan por su atención. Algunos estudiantes priorizan las materias que perciben como más directamente vinculadas a su especialidad o carrera, mientras que otros simplemente sienten el peso del agotamiento de mediados de semestre. En la primavera, los largos meses de invierno pueden aumentar esta fatiga, lo que hace que sea aún más difícil mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos (Rohan y Sigmon, 2000).

Este es el momento en que un instructor de idiomas debe pivotar, cambiando la dinámica del aula para reavivar la curiosidad y la motivación. Aunque los instructores se esfuerzan por incorporar actividades que se adapten a los cinco estilos de aprendizaje preferidos (Felder y Henriques, 1995)-Visual (aprendizaje a través de imágenes y comprensión espacial), auditivo (aprendizaje a través de la escucha y discusión), lectura/escritura (aprendizaje a través de interacción basada en texto), Kinesthetic (aprendizaje a través de movimiento y actividades prácticas) y multimodal (una combinación de múltiples estilos)-its is beneficiales). Estructurado y, después de un tiempo, clases predecibles con actividades que rompen el molde. La introducción de algo inesperado y diferente de la dinámica del aula establecida puede revitalizar a los estudiantes, fomentar la creatividad y mejorar su entusiasmo por el aprendizaje.

La música, en particular, ha sido durante mucho tiempo un aliado de instructores que enseñan un segundo idioma (L2), un idioma aprendido después de la lengua nativa, especialmente desde que el campo hizo la transición hacia un enfoque más comunicativo. Arraigado en la interacción y la aplicación del mundo real, el enfoque comunicativo prioriza el compromiso significativo sobre la memorización de memoria, ayudando a los estudiantes a desarrollar fluidez de formas naturales e inmersivas. La investigación ha destacado constantemente los beneficios de la música en la adquisición de L2, desde mejorar la pronunciación y las habilidades de escucha hasta mejorar la retención de vocabulario y la comprensión cultural (DeGrave, 2019; Kumar et al. 2022; Nuessel y Marshall, 2008; Vidal y Nordgren, 2024).

Sobre la base de esta tradición, la actividad que compartiremos aquí no solo incorpora música sino que también integra inteligencia artificial, agregando una nueva capa de compromiso y pensamiento crítico. Al usar la IA como herramienta en el proceso de aprendizaje, los estudiantes no solo se familiarizan con sus capacidades, sino que también desarrollan la capacidad de evaluar críticamente el contenido que genera. Este enfoque los alienta a reflexionar sobre el lenguaje, el significado y la interpretación mientras participan en el análisis de texto, la escritura creativa, la oratoria y la gamificación, todo dentro de un marco interactivo y culturalmente rico.

Descripción de la actividad: Desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre”

Objetivo:

Los estudiantes mejorarán su comprensión auditiva y su producción escrita en español analizando y recreando letras de canciones con la ayuda de ChatGPT. Si bien las instrucciones se presentan aquí en inglés, la actividad debe realizarse en el idioma de destino, ya sea que se enseñe el español u otro idioma.

Instrucciones:

1. Escuche y decodifique

- Divida la clase en grupos de 2-3 estudiantes.

- Elija una canción en español (por ejemplo, La Llorona por chavela vargas, Oye CÓMO VA por Tito Puente, Vivir mi Vida por Marc Anthony).

- Proporcione a cada grupo una versión incompleta de la letra con palabras faltantes.

- Los estudiantes escuchan la canción y completan los espacios en blanco.

2. Interpretar y discutir

- Dentro de sus grupos, los estudiantes analizan el significado de la canción.

- Discuten lo que creen que transmiten las letras, incluidas las emociones, los temas y cualquier referencia cultural que reconocan.

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- ¿Puedes identificar alguna referencia cultural en la canción? ¿Cómo dan forma a su significado?

- ¿Cómo influye la música (melodía, ritmo, etc.) en su interpretación de la letra?

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

3. Comparar con chatgpt

- Después de formar su propio análisis, los estudiantes preguntan a Chatgpt:

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- Comparan la interpretación de ChatGPT con sus propias ideas y discuten similitudes o diferencias.

4. Crea tu propio verso

- Cada grupo escribe un nuevo verso que coincide con el estilo y el ritmo de la canción.

- Pueden pedirle ayuda a ChatGPT: “Ayúdanos a escribir un nuevo verso para esta canción con el mismo estilo”.

5. Realizar y cantar

- Cada grupo presenta su nuevo verso a la clase.

- Si se sienten cómodos, pueden cantarlo usando la melodía original.

- Es beneficioso que el profesor tenga una versión de karaoke (instrumental) de la canción disponible para que las letras de los estudiantes se puedan escuchar claramente.

- Mostrar las nuevas letras en un monitor o proyector permite que otros estudiantes sigan y canten juntos, mejorando la experiencia colectiva.

6. Elección – El Grammy va a

Los estudiantes votan por diferentes categorías, incluyendo:

- Mejor adaptación

- Mejor reflexión

- Mejor rendimiento

- Mejor actitud

- Mejor colaboración

7. Reflexión final

- ¿Cuál fue la parte más desafiante de comprender la letra?

- ¿Cómo ayudó ChatGPT a interpretar la canción?

- ¿Qué nuevas palabras o expresiones aprendiste?

Pensamientos finales: música, IA y pensamiento crítico

Un desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre” (Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt: “Cantar y Descubrir”) es una actividad que he encontrado que es especialmente efectiva en mis cursos intermedios y avanzados. Lo uso cuando los estudiantes se sienten abrumados o distraídos, a menudo alrededor de los exámenes parciales, como una forma de ayudarlos a relajarse y reconectarse con el material. Sirve como un descanso refrescante, lo que permite a los estudiantes alejarse del estrés de las tareas y reenfocarse de una manera divertida e interactiva. Al incorporar música, creatividad y tecnología, mantenemos a los estudiantes presentes en la clase, incluso cuando todo lo demás parece exigir su atención.

Más allá de ofrecer una pausa bien merecida, esta actividad provoca discusiones atractivas sobre la interpretación del lenguaje, el contexto cultural y el papel de la IA en la educación. A medida que los estudiantes comparan sus propias interpretaciones de las letras de las canciones con las generadas por ChatGPT, comienzan a reconocer tanto el valor como las limitaciones de la IA. Estas ideas fomentan el pensamiento crítico, ayudándoles a desarrollar un enfoque más maduro de la tecnología y su impacto en su aprendizaje.

Agregar el elemento de karaoke mejora aún más la experiencia, dando a los estudiantes la oportunidad de realizar sus nuevos versos y divertirse mientras practica sus habilidades lingüísticas. Mostrar la letra en una pantalla hace que la actividad sea más inclusiva, lo que permite a todos seguirlo. Para hacerlo aún más agradable, seleccionando canciones que resuenen con los gustos de los estudiantes, ya sea un clásico como La Llorona O un éxito contemporáneo de artistas como Bad Bunny, Selena, Daddy Yankee o Karol G, hace que la actividad se sienta más personal y atractiva.

Esta actividad no se limita solo al aula. Es una gran adición a los clubes españoles o eventos especiales, donde los estudiantes pueden unirse a un amor compartido por la música mientras practican sus habilidades lingüísticas. Después de todo, ¿quién no disfruta de una buena parodia de su canción favorita?

Mezclar el aprendizaje de idiomas con música y tecnología, Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt Crea un entorno dinámico e interactivo que revitaliza a los estudiantes y profundiza su conexión con el lenguaje y el papel evolutivo de la IA. Convierte los momentos de agotamiento en oportunidades de creatividad, exploración cultural y entusiasmo renovado por el aprendizaje.

Angela Rodríguez Mooney, PhD, es profesora asistente de español y la Universidad de Mujeres de Texas.

Referencias

Baghurst, Timothy y Betty C. Kelley. “Un examen del estrés en los estudiantes universitarios en el transcurso de un semestre”. Práctica de promoción de la salud 15, no. 3 (2014): 438-447.

DeGrave, Pauline. “Música en el aula de idiomas extranjeros: cómo y por qué”. Revista de Enseñanza e Investigación de Lenguas 10, no. 3 (2019): 412-420.

Felder, Richard M. y Eunice R. Henriques. “Estilos de aprendizaje y enseñanza en la educación extranjera y de segundo idioma”. Anales de idiomas extranjeros 28, no. 1 (1995): 21-31.

Nuessel, Frank y April D. Marshall. “Prácticas y principios para involucrar a los tres modos comunicativos en español a través de canciones y música”. Hispania (2008): 139-146.

Kumar, Tribhuwan, Shamim Akhter, Mehrunnisa M. Yunus y Atefeh Shamsy. “Uso de la música y las canciones como herramientas pedagógicas en la enseñanza del inglés como contextos de idiomas extranjeros”. Education Research International 2022, no. 1 (2022): 1-9

Noticias

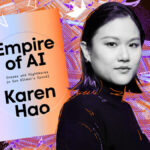

5 indicaciones de chatgpt que pueden ayudar a los adolescentes a lanzar una startup

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Teen emprendedor que usa chatgpt para ayudarlo con su negocio

El emprendimiento adolescente sigue en aumento. Según Junior Achievement Research, el 66% de los adolescentes estadounidenses de entre 13 y 17 años dicen que es probable que considere comenzar un negocio como adultos, con el monitor de emprendimiento global 2023-2024 que encuentra que el 24% de los jóvenes de 18 a 24 años son actualmente empresarios. Estos jóvenes fundadores no son solo soñando, están construyendo empresas reales que generan ingresos y crean un impacto social, y están utilizando las indicaciones de ChatGPT para ayudarlos.

En Wit (lo que sea necesario), la organización que fundó en 2009, hemos trabajado con más de 10,000 jóvenes empresarios. Durante el año pasado, he observado un cambio en cómo los adolescentes abordan la planificación comercial. Con nuestra orientación, están utilizando herramientas de IA como ChatGPT, no como atajos, sino como socios de pensamiento estratégico para aclarar ideas, probar conceptos y acelerar la ejecución.

Los emprendedores adolescentes más exitosos han descubierto indicaciones específicas que los ayudan a pasar de una idea a otra. Estas no son sesiones genéricas de lluvia de ideas: están utilizando preguntas específicas que abordan los desafíos únicos que enfrentan los jóvenes fundadores: recursos limitados, compromisos escolares y la necesidad de demostrar sus conceptos rápidamente.

Aquí hay cinco indicaciones de ChatGPT que ayudan constantemente a los emprendedores adolescentes a construir negocios que importan.

1. El problema del primer descubrimiento chatgpt aviso

“Me doy cuenta de que [specific group of people]

luchar contra [specific problem I’ve observed]. Ayúdame a entender mejor este problema explicando: 1) por qué existe este problema, 2) qué soluciones existen actualmente y por qué son insuficientes, 3) cuánto las personas podrían pagar para resolver esto, y 4) tres formas específicas en que podría probar si este es un problema real que vale la pena resolver “.

Un adolescente podría usar este aviso después de notar que los estudiantes en la escuela luchan por pagar el almuerzo. En lugar de asumir que entienden el alcance completo, podrían pedirle a ChatGPT que investigue la deuda del almuerzo escolar como un problema sistémico. Esta investigación puede llevarlos a crear un negocio basado en productos donde los ingresos ayuden a pagar la deuda del almuerzo, lo que combina ganancias con el propósito.

Los adolescentes notan problemas de manera diferente a los adultos porque experimentan frustraciones únicas, desde los desafíos de las organizaciones escolares hasta las redes sociales hasta las preocupaciones ambientales. Según la investigación de Square sobre empresarios de la Generación de la Generación Z, el 84% planea ser dueños de negocios dentro de cinco años, lo que los convierte en candidatos ideales para las empresas de resolución de problemas.

2. El aviso de chatgpt de chatgpt de chatgpt de realidad de la realidad del recurso

“Soy [age] años con aproximadamente [dollar amount] invertir y [number] Horas por semana disponibles entre la escuela y otros compromisos. Según estas limitaciones, ¿cuáles son tres modelos de negocio que podría lanzar de manera realista este verano? Para cada opción, incluya costos de inicio, requisitos de tiempo y los primeros tres pasos para comenzar “.

Este aviso se dirige al elefante en la sala: la mayoría de los empresarios adolescentes tienen dinero y tiempo limitados. Cuando un empresario de 16 años emplea este enfoque para evaluar un concepto de negocio de tarjetas de felicitación, puede descubrir que pueden comenzar con $ 200 y escalar gradualmente. Al ser realistas sobre las limitaciones por adelantado, evitan el exceso de compromiso y pueden construir hacia objetivos de ingresos sostenibles.

Según el informe de Gen Z de Square, el 45% de los jóvenes empresarios usan sus ahorros para iniciar negocios, con el 80% de lanzamiento en línea o con un componente móvil. Estos datos respaldan la efectividad de la planificación basada en restricciones: cuando funcionan los adolescentes dentro de las limitaciones realistas, crean modelos comerciales más sostenibles.

3. El aviso de chatgpt del simulador de voz del cliente

“Actúa como un [specific demographic] Y dame comentarios honestos sobre esta idea de negocio: [describe your concept]. ¿Qué te excitaría de esto? ¿Qué preocupaciones tendrías? ¿Cuánto pagarías de manera realista? ¿Qué necesitaría cambiar para que se convierta en un cliente? “

Los empresarios adolescentes a menudo luchan con la investigación de los clientes porque no pueden encuestar fácilmente a grandes grupos o contratar firmas de investigación de mercado. Este aviso ayuda a simular los comentarios de los clientes haciendo que ChatGPT adopte personas específicas.

Un adolescente que desarrolla un podcast para atletas adolescentes podría usar este enfoque pidiéndole a ChatGPT que responda a diferentes tipos de atletas adolescentes. Esto ayuda a identificar temas de contenido que resuenan y mensajes que se sienten auténticos para el público objetivo.

El aviso funciona mejor cuando se vuelve específico sobre la demografía, los puntos débiles y los contextos. “Actúa como un estudiante de último año de secundaria que solicita a la universidad” produce mejores ideas que “actuar como un adolescente”.

4. El mensaje mínimo de diseñador de prueba viable chatgpt

“Quiero probar esta idea de negocio: [describe concept] sin gastar más de [budget amount] o más de [time commitment]. Diseñe tres experimentos simples que podría ejecutar esta semana para validar la demanda de los clientes. Para cada prueba, explique lo que aprendería, cómo medir el éxito y qué resultados indicarían que debería avanzar “.

Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a adoptar la metodología Lean Startup sin perderse en la jerga comercial. El enfoque en “This Week” crea urgencia y evita la planificación interminable sin acción.

Un adolescente que desea probar un concepto de línea de ropa podría usar este indicador para diseñar experimentos de validación simples, como publicar maquetas de diseño en las redes sociales para evaluar el interés, crear un formulario de Google para recolectar pedidos anticipados y pedirles a los amigos que compartan el concepto con sus redes. Estas pruebas no cuestan nada más que proporcionar datos cruciales sobre la demanda y los precios.

5. El aviso de chatgpt del generador de claridad de tono

“Convierta esta idea de negocio en una clara explicación de 60 segundos: [describe your business]. La explicación debe incluir: el problema que resuelve, su solución, a quién ayuda, por qué lo elegirían sobre las alternativas y cómo se ve el éxito. Escríbelo en lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría “.

La comunicación clara separa a los empresarios exitosos de aquellos con buenas ideas pero una ejecución deficiente. Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a destilar conceptos complejos a explicaciones convincentes que pueden usar en todas partes, desde las publicaciones en las redes sociales hasta las conversaciones con posibles mentores.

El énfasis en el “lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría” es importante. Muchas plantillas de lanzamiento comercial suenan artificiales cuando se entregan jóvenes fundadores. La autenticidad es más importante que la jerga corporativa.

Más allá de las indicaciones de chatgpt: estrategia de implementación

La diferencia entre los adolescentes que usan estas indicaciones de manera efectiva y aquellos que no se reducen a seguir. ChatGPT proporciona dirección, pero la acción crea resultados.

Los jóvenes empresarios más exitosos con los que trabajo usan estas indicaciones como puntos de partida, no de punto final. Toman las sugerencias generadas por IA e inmediatamente las prueban en el mundo real. Llaman a clientes potenciales, crean prototipos simples e iteran en función de los comentarios reales.

Investigaciones recientes de Junior Achievement muestran que el 69% de los adolescentes tienen ideas de negocios, pero se sienten inciertos sobre el proceso de partida, con el miedo a que el fracaso sea la principal preocupación para el 67% de los posibles empresarios adolescentes. Estas indicaciones abordan esa incertidumbre al desactivar los conceptos abstractos en los próximos pasos concretos.

La imagen más grande

Los emprendedores adolescentes que utilizan herramientas de IA como ChatGPT representan un cambio en cómo está ocurriendo la educación empresarial. Según la investigación mundial de monitores empresariales, los jóvenes empresarios tienen 1,6 veces más probabilidades que los adultos de querer comenzar un negocio, y son particularmente activos en la tecnología, la alimentación y las bebidas, la moda y los sectores de entretenimiento. En lugar de esperar clases de emprendimiento formales o programas de MBA, estos jóvenes fundadores están accediendo a herramientas de pensamiento estratégico de inmediato.

Esta tendencia se alinea con cambios más amplios en la educación y la fuerza laboral. El Foro Económico Mundial identifica la creatividad, el pensamiento crítico y la resiliencia como las principales habilidades para 2025, la capacidad de las capacidades que el espíritu empresarial desarrolla naturalmente.

Programas como WIT brindan soporte estructurado para este viaje, pero las herramientas en sí mismas se están volviendo cada vez más accesibles. Un adolescente con acceso a Internet ahora puede acceder a recursos de planificación empresarial que anteriormente estaban disponibles solo para empresarios establecidos con presupuestos significativos.

La clave es usar estas herramientas cuidadosamente. ChatGPT puede acelerar el pensamiento y proporcionar marcos, pero no puede reemplazar el arduo trabajo de construir relaciones, crear productos y servir a los clientes. La mejor idea de negocio no es la más original, es la que resuelve un problema real para personas reales. Las herramientas de IA pueden ayudar a identificar esas oportunidades, pero solo la acción puede convertirlos en empresas que importan.

Noticias

Chatgpt vs. gemini: he probado ambos, y uno definitivamente es mejor

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Precio

ChatGPT y Gemini tienen versiones gratuitas que limitan su acceso a características y modelos. Los planes premium para ambos también comienzan en alrededor de $ 20 por mes. Las características de chatbot, como investigaciones profundas, generación de imágenes y videos, búsqueda web y más, son similares en ChatGPT y Gemini. Sin embargo, los planes de Gemini pagados también incluyen el almacenamiento en la nube de Google Drive (a partir de 2TB) y un conjunto robusto de integraciones en las aplicaciones de Google Workspace.

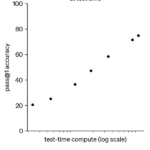

Los niveles de más alta gama de ChatGPT y Gemini desbloquean el aumento de los límites de uso y algunas características únicas, pero el costo mensual prohibitivo de estos planes (como $ 200 para Chatgpt Pro o $ 250 para Gemini Ai Ultra) los pone fuera del alcance de la mayoría de las personas. Las características específicas del plan Pro de ChatGPT, como el modo O1 Pro que aprovecha el poder de cálculo adicional para preguntas particularmente complicadas, no son especialmente relevantes para el consumidor promedio, por lo que no sentirá que se está perdiendo. Sin embargo, es probable que desee las características que son exclusivas del plan Ai Ultra de Gemini, como la generación de videos VEO 3.

Ganador: Géminis

Plataformas

Puede acceder a ChatGPT y Gemini en la web o a través de aplicaciones móviles (Android e iOS). ChatGPT también tiene aplicaciones de escritorio (macOS y Windows) y una extensión oficial para Google Chrome. Gemini no tiene aplicaciones de escritorio dedicadas o una extensión de Chrome, aunque se integra directamente con el navegador.

(Crédito: OpenAI/PCMAG)

Chatgpt está disponible en otros lugares, Como a través de Siri. Como se mencionó, puede acceder a Gemini en las aplicaciones de Google, como el calendario, Documento, ConducirGmail, Mapas, Mantener, FotosSábanas, y Música de YouTube. Tanto los modelos de Chatgpt como Gemini también aparecen en sitios como la perplejidad. Sin embargo, obtiene la mayor cantidad de funciones de estos chatbots en sus aplicaciones y portales web dedicados.

Las interfaces de ambos chatbots son en gran medida consistentes en todas las plataformas. Son fáciles de usar y no lo abruman con opciones y alternar. ChatGPT tiene algunas configuraciones más para jugar, como la capacidad de ajustar su personalidad, mientras que la profunda interfaz de investigación de Gemini hace un mejor uso de los bienes inmuebles de pantalla.

Ganador: empate

Modelos de IA

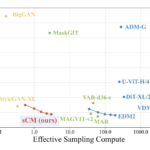

ChatGPT tiene dos series primarias de modelos, la serie 4 (su línea de conversación, insignia) y la Serie O (su compleja línea de razonamiento). Gemini ofrece de manera similar una serie Flash de uso general y una serie Pro para tareas más complicadas.

Los últimos modelos de Chatgpt son O3 y O4-Mini, y los últimos de Gemini son 2.5 Flash y 2.5 Pro. Fuera de la codificación o la resolución de una ecuación, pasará la mayor parte de su tiempo usando los modelos de la serie 4-Series y Flash. A continuación, puede ver cómo funcionan estos modelos en una variedad de tareas. Qué modelo es mejor depende realmente de lo que quieras hacer.

Ganador: empate

Búsqueda web

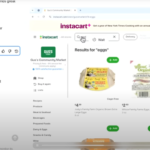

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden buscar información actualizada en la web con facilidad. Sin embargo, ChatGPT presenta mosaicos de artículos en la parte inferior de sus respuestas para una lectura adicional, tiene un excelente abastecimiento que facilita la vinculación de reclamos con evidencia, incluye imágenes en las respuestas cuando es relevante y, a menudo, proporciona más detalles en respuesta. Gemini no muestra nombres de fuente y títulos de artículos completos, e incluye mosaicos e imágenes de artículos solo cuando usa el modo AI de Google. El abastecimiento en este modo es aún menos robusto; Google relega las fuentes a los caretes que se pueden hacer clic que no resaltan las partes relevantes de su respuesta.

Como parte de sus experiencias de búsqueda en la web, ChatGPT y Gemini pueden ayudarlo a comprar. Si solicita consejos de compra, ambos presentan mosaicos haciendo clic en enlaces a los minoristas. Sin embargo, Gemini generalmente sugiere mejores productos y tiene una característica única en la que puede cargar una imagen tuya para probar digitalmente la ropa antes de comprar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Investigación profunda

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden generar informes que tienen docenas de páginas e incluyen más de 50 fuentes sobre cualquier tema. La mayor diferencia entre los dos se reduce al abastecimiento. Gemini a menudo cita más fuentes que CHATGPT, pero maneja el abastecimiento en informes de investigación profunda de la misma manera que lo hace en la búsqueda en modo AI, lo que significa caretas que se puede hacer clic sin destacados en el texto. Debido a que es más difícil conectar las afirmaciones en los informes de Géminis a fuentes reales, es más difícil creerles. El abastecimiento claro de ChatGPT con destacados en el texto es más fácil de confiar. Sin embargo, Gemini tiene algunas características de calidad de vida en ChatGPT, como la capacidad de exportar informes formateados correctamente a Google Docs con un solo clic. Su tono también es diferente. Los informes de ChatGPT se leen como publicaciones de foro elaboradas, mientras que los informes de Gemini se leen como documentos académicos.

Ganador: chatgpt

Generación de imágenes

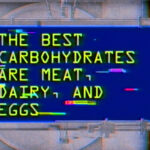

La generación de imágenes de ChatGPT impresiona independientemente de lo que solicite, incluso las indicaciones complejas para paneles o diagramas cómicos. No es perfecto, pero los errores y la distorsión son mínimos. Gemini genera imágenes visualmente atractivas más rápido que ChatGPT, pero rutinariamente incluyen errores y distorsión notables. Con indicaciones complicadas, especialmente diagramas, Gemini produjo resultados sin sentido en las pruebas.

Arriba, puede ver cómo ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Géminis (segunda diapositiva) les fue con el siguiente mensaje: “Genere una imagen de un estudio de moda con una decoración simple y rústica que contrasta con el espacio más agradable. Incluya un sofá marrón y paredes de ladrillo”. La imagen de ChatGPT limita los problemas al detalle fino en las hojas de sus plantas y texto en su libro, mientras que la imagen de Gemini muestra problemas más notables en su tubo de cordón y lámpara.

Ganador: chatgpt

¡Obtenga nuestras mejores historias!

Toda la última tecnología, probada por nuestros expertos

Regístrese en el boletín de informes de laboratorio para recibir las últimas revisiones de productos de PCMAG, comprar asesoramiento e ideas.

Al hacer clic en Registrarme, confirma que tiene más de 16 años y acepta nuestros Términos de uso y Política de privacidad.

¡Gracias por registrarse!

Su suscripción ha sido confirmada. ¡Esté atento a su bandeja de entrada!

Generación de videos

La generación de videos de Gemini es la mejor de su clase, especialmente porque ChatGPT no puede igualar su capacidad para producir audio acompañante. Actualmente, Google bloquea el último modelo de generación de videos de Gemini, VEO 3, detrás del costoso plan AI Ultra, pero obtienes más videos realistas que con ChatGPT. Gemini también tiene otras características que ChatGPT no, como la herramienta Flow Filmmaker, que le permite extender los clips generados y el animador AI Whisk, que le permite animar imágenes fijas. Sin embargo, tenga en cuenta que incluso con VEO 3, aún necesita generar videos varias veces para obtener un gran resultado.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité a ChatGPT y Gemini a mostrarme un solucionador de cubos de Rubik Rubik que resuelva un cubo. La persona en el video de Géminis se ve muy bien, y el audio acompañante es competente. Al final, hay una buena atención al detalle con el marco que se desplaza, simulando la detención de una grabación de selfies. Mientras tanto, Chatgpt luchó con su cubo, distorsionándolo en gran medida.

Ganador: Géminis

Procesamiento de archivos

Comprender los archivos es una fortaleza de ChatGPT y Gemini. Ya sea que desee que respondan preguntas sobre un manual, editen un currículum o le informen algo sobre una imagen, ninguno decepciona. Sin embargo, ChatGPT tiene la ventaja sobre Gemini, ya que ofrece un reconocimiento de imagen ligeramente mejor y respuestas más detalladas cuando pregunta sobre los archivos cargados. Ambos chatbots todavía a veces inventan citas de documentos proporcionados o malinterpretan las imágenes, así que asegúrese de verificar sus resultados.

Ganador: chatgpt

Escritura creativa

Chatgpt y Gemini pueden generar poemas, obras, historias y más competentes. CHATGPT, sin embargo, se destaca entre los dos debido a cuán únicas son sus respuestas y qué tan bien responde a las indicaciones. Las respuestas de Gemini pueden sentirse repetitivas si no calibra cuidadosamente sus solicitudes, y no siempre sigue todas las instrucciones a la carta.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Gemini (segunda diapositiva) con lo siguiente: “Sin hacer referencia a nada en su memoria o respuestas anteriores, quiero que me escriba un poema de verso gratuito. Preste atención especial a la capitalización, enjambment, ruptura de línea y puntuación. Dado que es un verso libre, no quiero un medidor familiar o un esquema de retiro de la rima, pero quiero que tenga un estilo de coohes. ChatGPT logró entregar lo que pedí en el aviso, y eso era distinto de las generaciones anteriores. Gemini tuvo problemas para generar un poema que incorporó cualquier cosa más allá de las comas y los períodos, y su poema anterior se lee de manera muy similar a un poema que generó antes.

Recomendado por nuestros editores

Ganador: chatgpt

Razonamiento complejo

Los modelos de razonamiento complejos de Chatgpt y Gemini pueden manejar preguntas de informática, matemáticas y física con facilidad, así como mostrar de manera competente su trabajo. En las pruebas, ChatGPT dio respuestas correctas un poco más a menudo que Gemini, pero su rendimiento es bastante similar. Ambos chatbots pueden y le darán respuestas incorrectas, por lo que verificar su trabajo aún es vital si está haciendo algo importante o tratando de aprender un concepto.

Ganador: chatgpt

Integración

ChatGPT no tiene integraciones significativas, mientras que las integraciones de Gemini son una característica definitoria. Ya sea que desee obtener ayuda para editar un ensayo en Google Docs, comparta una pestaña Chrome para hacer una pregunta, pruebe una nueva lista de reproducción de música de YouTube personalizada para su gusto o desbloquee ideas personales en Gmail, Gemini puede hacer todo y mucho más. Es difícil subestimar cuán integrales y poderosas son realmente las integraciones de Géminis.

Ganador: Géminis

Asistentes de IA

ChatGPT tiene GPT personalizados, y Gemini tiene gemas. Ambos son asistentes de IA personalizables. Tampoco es una gran actualización sobre hablar directamente con los chatbots, pero los GPT personalizados de terceros agregan una nueva funcionalidad, como el fácil acceso a Canva para editar imágenes generadas. Mientras tanto, terceros no pueden crear gemas, y no puedes compartirlas. Puede permitir que los GPT personalizados accedan a la información externa o tomen acciones externas, pero las GEM no tienen una funcionalidad similar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Contexto Windows y límites de uso

La ventana de contexto de ChatGPT sube a 128,000 tokens en sus planes de nivel superior, y todos los planes tienen límites de uso dinámicos basados en la carga del servidor. Géminis, por otro lado, tiene una ventana de contexto de 1,000,000 token. Google no está demasiado claro en los límites de uso exactos para Gemini, pero también son dinámicos dependiendo de la carga del servidor. Anecdóticamente, no pude alcanzar los límites de uso usando los planes pagados de Chatgpt o Gemini, pero es mucho más fácil hacerlo con los planes gratuitos.

Ganador: Géminis

Privacidad

La privacidad en Chatgpt y Gemini es una bolsa mixta. Ambos recopilan cantidades significativas de datos, incluidos todos sus chats, y usan esos datos para capacitar a sus modelos de IA de forma predeterminada. Sin embargo, ambos le dan la opción de apagar el entrenamiento. Google al menos no recopila y usa datos de Gemini para fines de capacitación en aplicaciones de espacio de trabajo, como Gmail, de forma predeterminada. ChatGPT y Gemini también prometen no vender sus datos o usarlos para la orientación de anuncios, pero Google y OpenAI tienen historias sórdidas cuando se trata de hacks, filtraciones y diversos fechorías digitales, por lo que recomiendo no compartir nada demasiado sensible.

Ganador: empate

Related posts

Trending

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoRemove.bg: La Revolución en la Edición de Imágenes que Debes Conocer

-

Tutoriales2 años ago

Tutoriales2 años agoCómo Comenzar a Utilizar ChatGPT: Una Guía Completa para Principiantes

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoStartups de IA en EE.UU. que han recaudado más de $100M en 2024

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoDeepgram: Revolucionando el Reconocimiento de Voz con IA

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoCómo Empezar con Popai.pro: Tu Espacio Personal de IA – Guía Completa, Instalación, Versiones y Precios

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoPerplexity aplicado al Marketing Digital y Estrategias SEO

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial Aplicada de 4Geeks Academy 2024

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial de UC Berkeley estratégico para negocios