Noticias

How Mark Zuckerberg went all-in to make Meta a major AI player and threaten OpenAI’s dominance

Published

1 año agoon

It was the summer of 2023, and the question at hand was whether to release a Llama into the wild.

The Llama in question wasn’t an animal: Llama 2 was the follow-up release of Meta’s generative AI mode—a would-be challenger to OpenAI’s GPT-4. The first Llama had come out a few months earlier. It had originally been intended only for researchers, but after it leaked online, it caught on with developers, who loved that it was free—unlike the large language models (LLMs) from OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic—as well as state-of-the-art. Also unlike those rivals, it was open source, which meant researchers, developers, and other users could access the underlying code and its “weights” (which determine how the model processes information) to use, modify, or improve it.

Yann LeCun, Meta’s chief AI scientist, and Joelle Pineau, VP of AI research and head of Meta’s FAIR (Fundamental AI Research) team, wanted to give Llama 2 a wide open-source release. They felt strongly that open-sourcing Llama 2 would enable the model to become more powerful more quickly, at a lower

cost. It could help the company catch up in a generative AI race in which it was seen as lagging badly behind its rivals, even as the company struggled to recover from a pivot to the metaverse whose meager offerings and cheesy, legless avatars had underwhelmed investors and customers

But there were also weighty reasons not to take that path. Once customers got accustomed to a free product, how could you ever monetize it? And as other execs pointed out in debates on the topic, the legal repercussions were potentially ugly: What if someone hijacked the model to go on a hacking spree? It didn’t help that two earlier releases of Meta open-source AI products had backfired badly, earning the company tongue-lashings from everyone from scientists to U.S. senators.

It would fall to CEO Mark Zuckerberg, Meta’s founder and controlling shareholder, to break the deadlock. Zuckerberg has long touted open-source technology (Facebook itself was built on open-source software), but he likes to gather all opinions; he spoke to “everybody who was either for, anti, or in the middle” on the open-source question, recalls Ahmad Al-Dahle, Meta’s head of generative AI. But in the end it was Zuckerberg himself, LeCun says, who made the final decision to release Llama 2 as an open source model: “He said, ‘Okay, we’re just going to do it.’” On July 18, 2023, Meta released Llama 2 “free for research and commercial use.”

In a post on his personal Facebook page, Zuckerberg doubled down on his decision. He emphasized his belief that open-source drives innovation by enabling more developers to build with a given technology. “I believe it would unlock more progress if the ecosystem were more open,” he wrote.

The episode could have just been another footnote in the fast-unfolding history of artificial intelligence. But in hindsight, the release of Llama 2 marked a crucial crossroads for Meta and Zuckerberg—the beginning of a remarkable comeback, all thanks to tech named after a furry camelid. By the time Llama 3 models were released in April and July 2024, Llama had mostly caught up to its closed-source rivals in speed and accuracy. On several benchmarks, the largest Llama 3 model matched or outperformed the best proprietary models from OpenAI and Anthropic. One advantage in Llama’s favor: Meta uses publicly shared data from billions of Facebook and Instagram accounts to train its AI models.

The Llama story could be a pivotal chapter in the ongoing philosophical debate between open-source AI models (generally more transparent, flexible, and cost-effective, but potentially easier to abuse) and closed models (often more tightly controlled but lacking transparency and more costly to develop). Just as crucially, Llama is at the core of a complete strategic pivot on the part of Meta to go all in on generative AI. Zuckerberg is now seen as a champion of “democratizing tech” among Silicon Valley developers—just two years after he and his company were being questioned, and sometimes mocked, for going all in on the metaverse, and vilified for having contributed to political polarization, extremism, and harming the mental health of teenagers.

DeSean McClinton-Holland for Fortune

While ChatGPT remains the dominant gen AI tool in the popular imagination, Llama models now power many, if not most, of the Meta products that billions of consumers encounter every day. Meta’s AI assistant, which reaches across Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger, is built with Llama, while users can create their own AI chatbot with AI Studio. Text-generation tools for advertisers are built on Llama. Llama helps power the conversational assistant that is part of Meta’s hit Ray-Ban glasses, and the feature in the Quest headset that lets users ask questions about their surroundings. The company is said to be developing its own AI-powered search engine. And outside its walls, Llama models have been downloaded over 600 million times on sites like open-source AI community Hugging Face.

Still, the pivot has perplexed many Meta watchers. The company has spent billions to build the Llama models: On its third-quarter earnings call, Meta announced that it projects capital expenditures for 2024 to reach as high as $40 billion, with a “significant” increase likely in 2025. Meanwhile, it’s giving Llama away for free to thousands of companies, including giants like Goldman Sachs, AT&T, and Accenture. Some investors are struggling to understand where and when, exactly, Meta’s revenue would start to justify the eye-watering spend.

Why open-sourcing Llama is good for Meta is “the big puzzle,” says Abhishek Nagaraj, associate professor at the University of California at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, adding that it’s “hard to justify” from a purely economic standpoint.

Nonetheless, Llama’s contrarian success has allowed Zuckerberg to shrug off the lukewarm response to his metaverse ambitions and the company’s painful “year of efficiency” in late 2022 and early 2023. The rise of Llama has also given Zuckerberg a chance to address a longsimmering sore point in his otherwise meteoric career: the fact that Facebook, and now Meta, have so often seen their services and products constrained by rules imposed by Apple and Google—the rival giants whose app stores are Meta’s primary points of distribution in the mobiledevice era. As he wrote in a July blog post: “We must ensure that we always have access to the best technology, and that we’re not locking into a competitor’s closed ecosystem where they can restrict what we build.”

“We got incoming requests from people who said, ‘You have to open-source that stuff. It’s so valuable that you could create an entire industry, like a new internet.’”

Yann Lecun, describing reactions to the 2023 leak of Llama

With Llama, Meta and Zuckerberg have the chance to set a new industry standard. “I think we’re going to look back at Llama 3.1 as an inflection point in the industry, where open-source AI started to become the industry standard, just like Linux is,” he said on Meta’s July earnings call—invoking the open-source project that disrupted the dominance of proprietary operating systems like Microsoft Windows.

Perhaps it’s this possibility that is giving Zuckerberg some new swagger. At 40, two decades after he cofounded Facebook, he appears to be enjoying what many are calling his “Zuckaissance”—a personal and professional glow-up. His once close-cropped haircut has given way to lush curls, the drab hoodies are swapped for gold chains and oversize black T-shirts, and his hard-edged expressions have softened into relaxed smiles. He even found time in November to collaborate with T-Pain on a remake of the hip-hop hit “Get Low”—an anniversary gift to his wife, Priscilla Chan.

In the long run, OpenAI’s ChatGPT may be seen as the fiery spark that ignited the generative AI boom. But for now, at least, Llama’s own future’s so bright, Zuckerberg has gotta wear AI-powered Ray-Ban shades.

Meta’s work on AI began in earnest in 2013, when Zuckerberg handpicked LeCun, a longtime NYU professor and an AI luminary, to run Facebook’s new FAIR lab. LeCun recalls that when he began discussing the role, his first question was whether Facebook would open-source its work. “Nobody has a monopoly on good ideas,” he told Zuckerberg, “and we need to collaborate as much as we can.” LeCun was thrilled with the answer he got: “Oh, you don’t have to worry about it. We already open-source our platform software and everything.”

But prior to the generative AI boom, Meta’s use of AI was mostly behind the scenes—either research focused or integrated under the hood of its recommendation algorithms and content moderation. There were no big plans for a consumer-facing AI product like a chatbot—particularly not when Zuckerberg’s attention was focused on the metaverse.

Generative AI began to take off with OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT, just as the Meta pivot was looking particularly unwise. With metaverse spending through the roof and consumers utterly uninterested, Meta’s stock hit a seven-year low, inspiring headlines like, “How Much Trouble Is Mark Zuckerberg In?” The company began laying off thousands of employees.

Meta’s first widely noticed foray into gen AI didn’t fare much better. In November 2022, FAIR released a demo of an LLM chatbot, trained on scientific texts, called Galactica. Like previous FAIR models, Galactica was released as open-source, allowing free access to the “brains” of the model. This openness was meant to enable researchers to study how Galactica functioned.

But these were the days before the public was fully aware of LLMs’ tendency to hallucinate—to sometimes spit out answers that are convincing, confident, and wrong. Many scientists were appalled by the Galactica chatbot’s very unscientific output, which included citing research papers that didn’t exist, on topics such as how to make napalm in a bathtub; the benefits of eating crushed glass; and “why homosexuals are evil.” Critics called Galactica “unethical” and “the most dangerous thing Meta’s made yet.”

After three days of intense criticism, Meta researchers shut down Galactica. Twelve days later, OpenAI released ChatGPT, which quickly went viral around the world, tapping into the cultural zeitgeist (despite its own serious hallucination issues).

Bruised but undeterred, researchers at FAIR spent the winter fine-tuning a new family of generative AI models called LLaMA (short for Large Language Models Meta AI). After the Galactica backlash, Meta was cautious: Instead of fully opening the code and model weights to all, Meta required researchers to apply for access, and no commercial license was offered. When asked why, LeCun responded on X: “Because last time we made an LLM available to everyone…people threw vitriol at our face and told us this was going to destroy the fabric of society.”

Despite these restrictions, the full model leaked online within weeks, spreading across 4chan and various AI communities. “It felt a bit like Swiss cheese,” Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, says of the failed attempt to keep Llama behind closed doors. Meta filed takedown requests against sites posting the model online in an attempt to control the spread. Some critics warned of serious repercussions and excoriated Meta: “Get ready for loads of personalized spam and phishing attacks,” cybersecurity researcher Jeffrey Ladish posted on X.

The consternation even reached Capitol Hill. In June 2023, two U.S. senators wrote a letter to Zuckerberg, criticizing Llama’s release and warning of its potential misuse for fraud, malware, harassment, and privacy violations. The letter said that Meta’s approach to distributing advanced AI “raises serious questions about the potential for misuse or abuse.”

But at the same time, LeCun says, he and other Meta leaders were taken aback by the sheer demand for the leaked Llama model from researchers and developers. These would-be users wanted the flexibility and control that would come with open access to a profoundly powerful LLM. A law firm, for example, could use it to train a specialized model for legal use—and own the intellectual property. A health care company could audit and manage the data behind the model, ensuring HIPAA compliance. Researchers could experiment and examine the inner workings of the model. “We got incoming requests from people who said, ‘You have to open-source that stuff. It’s so valuable that you could create an entire industry, like a new internet,’” LeCun says

Messages came directly to Zuckerberg, to CTO Andrew “Boz” Bosworth, and to LeCun, leading to weekly calls in which the leaders debated what they should do. Should they open-source the next release? Did the benefits outweigh the risks? By midsummer, Zuckerberg’s mind was made up, with backing from Pineau and LeCun—leading to the big July 2023 reveal.

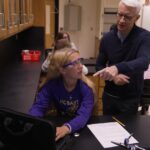

Cayce Clifford for Fortune

Llama 2 was not entirely open. Meta did not disclose the datasets—including all that Facebook and Instagram material—used to train the model, which are widely regarded as its key competitive advantage. It also restricted usage by companies with more than 700 million monthly active users, primarily meant to deter Meta’s Big Tech competitors. But the source code and model weights could be downloaded, and Meta encouraged users to contribute improvements, bug fixes, and refinements of results to a collaborative community.

Even before the Llama 2 release, Zuckerberg had laid the groundwork to treat it like Meta’s next big thing. After the first Llama model was released, in February 2023, Zuckerberg quickly put together a team from across the company, including FAIR, to focus on accelerating generative AI R&D in order to deploy it in Meta app features and tools. He chose Ahmad Al-Dahle, a former Apple executive who had joined Meta in 2020 to work on metaverse products, to lead the new team.

At an internal all-hands meeting in June 2023, Zuckerberg shared his vision for Meta’s AI-powered future. Meta was building generative AI into all of its products, he said, and he reaffirmed the company’s commitment to an “open science-based approach” to AI research. “I had a big remit,” Al-Dahle says: “Develop state-of-theart models; put them in product at record speed.”

In other words: It was game on for Llama.

Meta’s strategy can seem counterintuitive, coming from a company with $135 billion in annual revenue. Open-source software has typically been seen as a way to democratize technology to the advantage of small startups or under-resourced teams— the kinds scrambling to compete with giants like Meta.

In a July 2024 blog post called “Open Source Is the Path Forward,” Zuckerberg made it clear that giving away Llama is not an altruistic move. Open-sourcing, he said, would give Meta a competitive edge in the AI race—and could eventually make Llama the go-to platform for generative AI. Just as important, he wrote: “Openly releasing Llama doesn’t undercut our revenue, sustainability, or ability to invest in research like it does for closed providers” like OpenAI or Google.

Now that Llama has had a year-plus to prove itself, some are finding Zuck’s case persuasive. Shweta Khajuria, an analyst at Wolfe Research who coverscMeta, calls releasing Llama as open-source “a stroke of genius” that will enable Meta to attract top talent, accelerate innovation on its own platform, develop new revenue sources, and extend its longevity. Already, she explains, open-sourcing Llama basically allowed Meta to quickly catch up to OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic, in part because thousands of developers are building and improving on Llama at a blistering pace. “If they had not open-sourced it, it probably would have taken a much longer time to be at bar with other frontier models,” she says.

Khajuria believes there will be plenty of new monetization opportunities for Meta down the line, such as subscription and advertising options for current Meta AI features based on Llama, as well as AI-powered in-app business messaging. “Meta benefits from having billions of users where Perplexity and Claude and ChatGPT don’t necessarily have that base,” she says. “Once they have a critical mass of users and usage around the world, they can monetize.”

Zuckerberg has also alluded to the fact that AI-generated content itself will be valuable (though others have criticized such content as “slop”). On the recent earnings call, Zuckerberg said: “I think we’re going to add a whole new category of content, which is AI-generated or AI-summarized content, or existing content pulled together by AI in some way, and I think that that’s gonna be very exciting for Facebook and Instagram and maybe Threads, or other kinds of feed experiences over time.”

Patrick Wendell is CTO and cofounder of data and AI company Databricks, which released Meta’s Llama 3.1 models on its platform in July. He sees Meta’s move as much more far-reaching. If the internet was the first big wave of technology, which enabled Facebook’s creation, and mobile was the second, dominated by Apple and Google, “I think [Zuckerberg’s] calculus is the third big wave is coming, and he does not want to have one or two companies completely control all access to AI,” Wendell says. “One way you can avoid that is by basically commoditizing the market, giving away the core IP for free…so no one gains a monopoly.”

Some critics argue that Meta shouldn’t be using the term “open-source” at all. Current versions of Llama still have restrictions that traditional open-source software doesn’t (including lack of access to datasets). In October, the Open Source Initiative, which coined the term, criticized Meta for “confusing” users and “polluting” the nomenclature, and noted that Google and Microsoft had dropped their use of the term (using the phrase “open weights” instead). Clegg, Meta’s global affairs chief, is blunt in his rebuttal: He says the debate reminds him of “folks who get very agitated about how vinyl is the only true kind of definition of good music.” Only a handful of scientific and low-performing models would fit the definition, he continues: “No one has copyright IP ownership over these two English words.”

Nomenclature aside, Meta is winning where it matters. Nathan Lambert, a research scientist at the nonprofit Allen Institute for AI, says that while definitions might be quibbled about, more than 90% of the open-source AI models currently in use are based on Llama. Open-source coders accept that Zuckerberg “has some corporate realities that will distort his messaging,” he says. “At the end of the day, the community needs Llama models.

Internally at Meta, Llama and revenue-generating businesses are increasingly inextricable. In January, Zuckerberg moved FAIR, the AI research group, into the same part of the company as the team deploying generative AI products across Meta’s apps. LeCun and Pineau now report directly to chief product officer Chris Cox, as does Al-Dahle. “I think it makes a lot of sense to put [FAIR] close to the family of app products,” says Pineau; she points out that even before the reshuffle, research her team worked on often ended up in Meta products just a few months later.

Zuckerberg also tasked FAIR with something far more ambitious: developing artificial general intelligence (AGI), a type of AI that possesses humanlike intelligence. The company prefers to use the term AMI (“advanced machine intelligence”), but whatever it’s called, Pineau says, Meta now has a “real road map” to create it—one that relies, presumably, on a thriving Llama. Meanwhile the company is hard at work on Llama 4 models currently being trained on a cluster of over 100,000 pricey Nvidia GPUs, a cluster that Zuckerberg recently said was “bigger than anything that I’ve seen reported for what others are doing.”

Not everyone loves the idea of a bigger-than-anything Llama. For years, Zuckerberg and his company have grappled with public mistrust over the way it has used other types of AI to personalize news feeds, moderate content, and target ads across Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. Critics have accused its algorithms of exacerbating political polarization, adolescent mental-health crises, and the spread of misinformation (accusations Meta has denied or rebutted); it was perhaps inevitable that Llama would face extra scrutiny.

Zuckerberg “does not want to have one or two companies completely control all access to AI. One way you can avoid that is by giving away the core IP for free, so no one gains a monopoly.”

PATRICK WENDELL, cofounder and CTO, Databricks

Some critics fear that an open-source model like Llama is dangerous in the hands of malicious actors, precisely because it’s too open. Those concerns may grow in today’s tense geopolitical atmosphere. On Nov. 1, Reuters reported that China’s army had built AI applications for military use on the back of an early version of Llama.

An incoming Trump administration could make it even more complicated to keep Llama open. Trump’s economic nationalism would suggest that he would certainly not want China (or any other country) to access American-made state-of-the-art AI models. But Llama’s future may depend on who has Trump’s ear: Vice President–elect JD Vance has spoken out in support of open-source AI in the past, while Elon Musk’s xAI has open-sourced its chatbot Grok (and Musk famously cofounded OpenAI as an open-source lab).

Even some of Zuckerberg’s oldest friends have concerns about this kind of arms race. Dustin Moskovitz, a cofounder of Facebook and now CEO of Asana (and the founder of Open Philanthropy, one of the biggest funders of AI safety initiatives), says that while he is not against open-source LLMs, “I don’t think it’s appropriate to keep releasing ever more powerful versions.”

But Zuckerberg and his allies, both within Meta and without, argue that the risks of open-source models are actually less than those built behind proprietary closed doors. Preemptive regulation of theoretical harms of open-source AI will stifle innovation, they say. In a cowritten essay in August, Zuckerberg and Spotify cofounder Daniel Ek noted that open-source development is “the best shot at harnessing AI to drive progress and create economic opportunity and security for everyone.”

Whatever the outcome of Meta’s increasingly loud open-source activism, many argue that Zuckerberg is exactly the right messenger. His personal involvement in promoting Llama and open-source, insiders agree, is the key reason Meta has been able to move with such speed and focus. “He’s one of a few founder leaders left at these big tech companies,” says Clegg. “One of the great advantages of that means you have a very short line of command.”

Zuckerberg also has been active in recruiting AI talent, often reaching out personally. A March 2024 report said that Zuckerberg had been luring researchers from Google’s DeepMind with personal emails in messages that stressed how important AI was to the company.

Erik Meijer, who spent eight years at Meta leading a team focused on machine learning—before being laid off in November 2022—believes such a total shift is only possible with someone like Zuckerberg at the top. “It’s like pivoting a giant supertanker,” he says. “He’s a little bit like a cult hero inside the company, in a good sense, so I think that helps get all the noses in the same direction.” Zuckerberg’s new personal makeover, Meijer mused, is “maybe a very externally visible sign of renewal.”

Zuckerberg’s renewal, and Meta’s transformation, are sure to test investor patience due to skyrocketing capital expenditures. Khajuria, the Wolfe analyst, says investors will tolerate it for now “because Meta has laid the groundwork of telling folks what the opportunity is.” That said, if revenue does not begin accelerating, exiting 2025 into 2026, “I think investors will start losing patience,” she warns. (Zuckerberg is somewhat insulated from investor discontent; he controls about 61% of voting shares at Meta.)

One thing is clear, LeCun says: The kind of gamble Meta is taking, with its massive investment in GPUs and all things generative AI, requires a leader willing to take big swings. And Meta has not only that leader, but a massively profitable core business to fund the vision. As a result, Meta is back at the center of the most important conversation at the intersection of tech and business—and it’s not a conversation about legless metaverse avatars.

This article appears in the December 2024/January 2025 issue of Fortune as part of the 100 Most Powerful People in Business list.

You may like

Noticias

Revivir el compromiso en el aula de español: un desafío musical con chatgpt – enfoque de la facultad

Published

8 meses agoon

6 junio, 2025

A mitad del semestre, no es raro notar un cambio en los niveles de energía de sus alumnos (Baghurst y Kelley, 2013; Kumari et al., 2021). El entusiasmo inicial por aprender un idioma extranjero puede disminuir a medida que otros cursos con tareas exigentes compitan por su atención. Algunos estudiantes priorizan las materias que perciben como más directamente vinculadas a su especialidad o carrera, mientras que otros simplemente sienten el peso del agotamiento de mediados de semestre. En la primavera, los largos meses de invierno pueden aumentar esta fatiga, lo que hace que sea aún más difícil mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos (Rohan y Sigmon, 2000).

Este es el momento en que un instructor de idiomas debe pivotar, cambiando la dinámica del aula para reavivar la curiosidad y la motivación. Aunque los instructores se esfuerzan por incorporar actividades que se adapten a los cinco estilos de aprendizaje preferidos (Felder y Henriques, 1995)-Visual (aprendizaje a través de imágenes y comprensión espacial), auditivo (aprendizaje a través de la escucha y discusión), lectura/escritura (aprendizaje a través de interacción basada en texto), Kinesthetic (aprendizaje a través de movimiento y actividades prácticas) y multimodal (una combinación de múltiples estilos)-its is beneficiales). Estructurado y, después de un tiempo, clases predecibles con actividades que rompen el molde. La introducción de algo inesperado y diferente de la dinámica del aula establecida puede revitalizar a los estudiantes, fomentar la creatividad y mejorar su entusiasmo por el aprendizaje.

La música, en particular, ha sido durante mucho tiempo un aliado de instructores que enseñan un segundo idioma (L2), un idioma aprendido después de la lengua nativa, especialmente desde que el campo hizo la transición hacia un enfoque más comunicativo. Arraigado en la interacción y la aplicación del mundo real, el enfoque comunicativo prioriza el compromiso significativo sobre la memorización de memoria, ayudando a los estudiantes a desarrollar fluidez de formas naturales e inmersivas. La investigación ha destacado constantemente los beneficios de la música en la adquisición de L2, desde mejorar la pronunciación y las habilidades de escucha hasta mejorar la retención de vocabulario y la comprensión cultural (DeGrave, 2019; Kumar et al. 2022; Nuessel y Marshall, 2008; Vidal y Nordgren, 2024).

Sobre la base de esta tradición, la actividad que compartiremos aquí no solo incorpora música sino que también integra inteligencia artificial, agregando una nueva capa de compromiso y pensamiento crítico. Al usar la IA como herramienta en el proceso de aprendizaje, los estudiantes no solo se familiarizan con sus capacidades, sino que también desarrollan la capacidad de evaluar críticamente el contenido que genera. Este enfoque los alienta a reflexionar sobre el lenguaje, el significado y la interpretación mientras participan en el análisis de texto, la escritura creativa, la oratoria y la gamificación, todo dentro de un marco interactivo y culturalmente rico.

Descripción de la actividad: Desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre”

Objetivo:

Los estudiantes mejorarán su comprensión auditiva y su producción escrita en español analizando y recreando letras de canciones con la ayuda de ChatGPT. Si bien las instrucciones se presentan aquí en inglés, la actividad debe realizarse en el idioma de destino, ya sea que se enseñe el español u otro idioma.

Instrucciones:

1. Escuche y decodifique

- Divida la clase en grupos de 2-3 estudiantes.

- Elija una canción en español (por ejemplo, La Llorona por chavela vargas, Oye CÓMO VA por Tito Puente, Vivir mi Vida por Marc Anthony).

- Proporcione a cada grupo una versión incompleta de la letra con palabras faltantes.

- Los estudiantes escuchan la canción y completan los espacios en blanco.

2. Interpretar y discutir

- Dentro de sus grupos, los estudiantes analizan el significado de la canción.

- Discuten lo que creen que transmiten las letras, incluidas las emociones, los temas y cualquier referencia cultural que reconocan.

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- ¿Puedes identificar alguna referencia cultural en la canción? ¿Cómo dan forma a su significado?

- ¿Cómo influye la música (melodía, ritmo, etc.) en su interpretación de la letra?

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

3. Comparar con chatgpt

- Después de formar su propio análisis, los estudiantes preguntan a Chatgpt:

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- Comparan la interpretación de ChatGPT con sus propias ideas y discuten similitudes o diferencias.

4. Crea tu propio verso

- Cada grupo escribe un nuevo verso que coincide con el estilo y el ritmo de la canción.

- Pueden pedirle ayuda a ChatGPT: “Ayúdanos a escribir un nuevo verso para esta canción con el mismo estilo”.

5. Realizar y cantar

- Cada grupo presenta su nuevo verso a la clase.

- Si se sienten cómodos, pueden cantarlo usando la melodía original.

- Es beneficioso que el profesor tenga una versión de karaoke (instrumental) de la canción disponible para que las letras de los estudiantes se puedan escuchar claramente.

- Mostrar las nuevas letras en un monitor o proyector permite que otros estudiantes sigan y canten juntos, mejorando la experiencia colectiva.

6. Elección – El Grammy va a

Los estudiantes votan por diferentes categorías, incluyendo:

- Mejor adaptación

- Mejor reflexión

- Mejor rendimiento

- Mejor actitud

- Mejor colaboración

7. Reflexión final

- ¿Cuál fue la parte más desafiante de comprender la letra?

- ¿Cómo ayudó ChatGPT a interpretar la canción?

- ¿Qué nuevas palabras o expresiones aprendiste?

Pensamientos finales: música, IA y pensamiento crítico

Un desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre” (Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt: “Cantar y Descubrir”) es una actividad que he encontrado que es especialmente efectiva en mis cursos intermedios y avanzados. Lo uso cuando los estudiantes se sienten abrumados o distraídos, a menudo alrededor de los exámenes parciales, como una forma de ayudarlos a relajarse y reconectarse con el material. Sirve como un descanso refrescante, lo que permite a los estudiantes alejarse del estrés de las tareas y reenfocarse de una manera divertida e interactiva. Al incorporar música, creatividad y tecnología, mantenemos a los estudiantes presentes en la clase, incluso cuando todo lo demás parece exigir su atención.

Más allá de ofrecer una pausa bien merecida, esta actividad provoca discusiones atractivas sobre la interpretación del lenguaje, el contexto cultural y el papel de la IA en la educación. A medida que los estudiantes comparan sus propias interpretaciones de las letras de las canciones con las generadas por ChatGPT, comienzan a reconocer tanto el valor como las limitaciones de la IA. Estas ideas fomentan el pensamiento crítico, ayudándoles a desarrollar un enfoque más maduro de la tecnología y su impacto en su aprendizaje.

Agregar el elemento de karaoke mejora aún más la experiencia, dando a los estudiantes la oportunidad de realizar sus nuevos versos y divertirse mientras practica sus habilidades lingüísticas. Mostrar la letra en una pantalla hace que la actividad sea más inclusiva, lo que permite a todos seguirlo. Para hacerlo aún más agradable, seleccionando canciones que resuenen con los gustos de los estudiantes, ya sea un clásico como La Llorona O un éxito contemporáneo de artistas como Bad Bunny, Selena, Daddy Yankee o Karol G, hace que la actividad se sienta más personal y atractiva.

Esta actividad no se limita solo al aula. Es una gran adición a los clubes españoles o eventos especiales, donde los estudiantes pueden unirse a un amor compartido por la música mientras practican sus habilidades lingüísticas. Después de todo, ¿quién no disfruta de una buena parodia de su canción favorita?

Mezclar el aprendizaje de idiomas con música y tecnología, Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt Crea un entorno dinámico e interactivo que revitaliza a los estudiantes y profundiza su conexión con el lenguaje y el papel evolutivo de la IA. Convierte los momentos de agotamiento en oportunidades de creatividad, exploración cultural y entusiasmo renovado por el aprendizaje.

Angela Rodríguez Mooney, PhD, es profesora asistente de español y la Universidad de Mujeres de Texas.

Referencias

Baghurst, Timothy y Betty C. Kelley. “Un examen del estrés en los estudiantes universitarios en el transcurso de un semestre”. Práctica de promoción de la salud 15, no. 3 (2014): 438-447.

DeGrave, Pauline. “Música en el aula de idiomas extranjeros: cómo y por qué”. Revista de Enseñanza e Investigación de Lenguas 10, no. 3 (2019): 412-420.

Felder, Richard M. y Eunice R. Henriques. “Estilos de aprendizaje y enseñanza en la educación extranjera y de segundo idioma”. Anales de idiomas extranjeros 28, no. 1 (1995): 21-31.

Nuessel, Frank y April D. Marshall. “Prácticas y principios para involucrar a los tres modos comunicativos en español a través de canciones y música”. Hispania (2008): 139-146.

Kumar, Tribhuwan, Shamim Akhter, Mehrunnisa M. Yunus y Atefeh Shamsy. “Uso de la música y las canciones como herramientas pedagógicas en la enseñanza del inglés como contextos de idiomas extranjeros”. Education Research International 2022, no. 1 (2022): 1-9

Noticias

5 indicaciones de chatgpt que pueden ayudar a los adolescentes a lanzar una startup

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

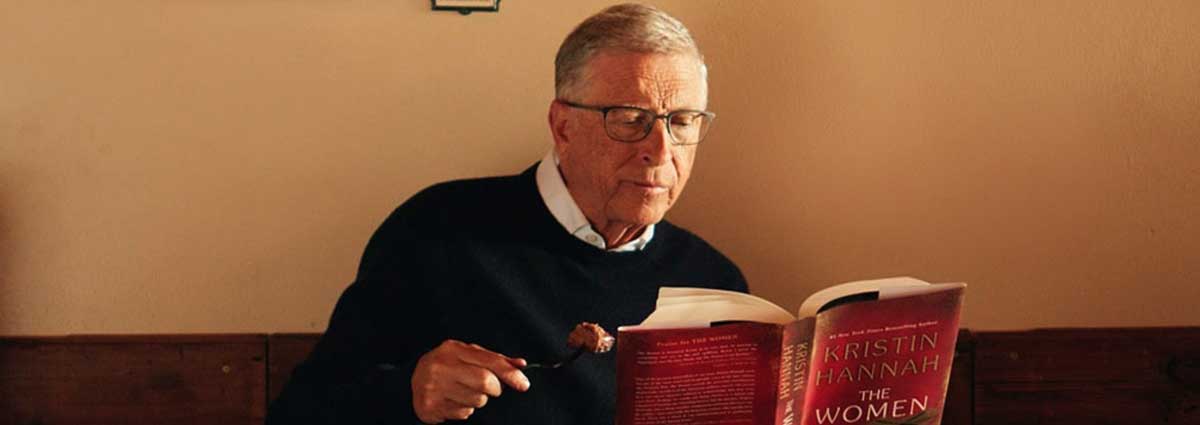

Teen emprendedor que usa chatgpt para ayudarlo con su negocio

El emprendimiento adolescente sigue en aumento. Según Junior Achievement Research, el 66% de los adolescentes estadounidenses de entre 13 y 17 años dicen que es probable que considere comenzar un negocio como adultos, con el monitor de emprendimiento global 2023-2024 que encuentra que el 24% de los jóvenes de 18 a 24 años son actualmente empresarios. Estos jóvenes fundadores no son solo soñando, están construyendo empresas reales que generan ingresos y crean un impacto social, y están utilizando las indicaciones de ChatGPT para ayudarlos.

En Wit (lo que sea necesario), la organización que fundó en 2009, hemos trabajado con más de 10,000 jóvenes empresarios. Durante el año pasado, he observado un cambio en cómo los adolescentes abordan la planificación comercial. Con nuestra orientación, están utilizando herramientas de IA como ChatGPT, no como atajos, sino como socios de pensamiento estratégico para aclarar ideas, probar conceptos y acelerar la ejecución.

Los emprendedores adolescentes más exitosos han descubierto indicaciones específicas que los ayudan a pasar de una idea a otra. Estas no son sesiones genéricas de lluvia de ideas: están utilizando preguntas específicas que abordan los desafíos únicos que enfrentan los jóvenes fundadores: recursos limitados, compromisos escolares y la necesidad de demostrar sus conceptos rápidamente.

Aquí hay cinco indicaciones de ChatGPT que ayudan constantemente a los emprendedores adolescentes a construir negocios que importan.

1. El problema del primer descubrimiento chatgpt aviso

“Me doy cuenta de que [specific group of people]

luchar contra [specific problem I’ve observed]. Ayúdame a entender mejor este problema explicando: 1) por qué existe este problema, 2) qué soluciones existen actualmente y por qué son insuficientes, 3) cuánto las personas podrían pagar para resolver esto, y 4) tres formas específicas en que podría probar si este es un problema real que vale la pena resolver “.

Un adolescente podría usar este aviso después de notar que los estudiantes en la escuela luchan por pagar el almuerzo. En lugar de asumir que entienden el alcance completo, podrían pedirle a ChatGPT que investigue la deuda del almuerzo escolar como un problema sistémico. Esta investigación puede llevarlos a crear un negocio basado en productos donde los ingresos ayuden a pagar la deuda del almuerzo, lo que combina ganancias con el propósito.

Los adolescentes notan problemas de manera diferente a los adultos porque experimentan frustraciones únicas, desde los desafíos de las organizaciones escolares hasta las redes sociales hasta las preocupaciones ambientales. Según la investigación de Square sobre empresarios de la Generación de la Generación Z, el 84% planea ser dueños de negocios dentro de cinco años, lo que los convierte en candidatos ideales para las empresas de resolución de problemas.

2. El aviso de chatgpt de chatgpt de chatgpt de realidad de la realidad del recurso

“Soy [age] años con aproximadamente [dollar amount] invertir y [number] Horas por semana disponibles entre la escuela y otros compromisos. Según estas limitaciones, ¿cuáles son tres modelos de negocio que podría lanzar de manera realista este verano? Para cada opción, incluya costos de inicio, requisitos de tiempo y los primeros tres pasos para comenzar “.

Este aviso se dirige al elefante en la sala: la mayoría de los empresarios adolescentes tienen dinero y tiempo limitados. Cuando un empresario de 16 años emplea este enfoque para evaluar un concepto de negocio de tarjetas de felicitación, puede descubrir que pueden comenzar con $ 200 y escalar gradualmente. Al ser realistas sobre las limitaciones por adelantado, evitan el exceso de compromiso y pueden construir hacia objetivos de ingresos sostenibles.

Según el informe de Gen Z de Square, el 45% de los jóvenes empresarios usan sus ahorros para iniciar negocios, con el 80% de lanzamiento en línea o con un componente móvil. Estos datos respaldan la efectividad de la planificación basada en restricciones: cuando funcionan los adolescentes dentro de las limitaciones realistas, crean modelos comerciales más sostenibles.

3. El aviso de chatgpt del simulador de voz del cliente

“Actúa como un [specific demographic] Y dame comentarios honestos sobre esta idea de negocio: [describe your concept]. ¿Qué te excitaría de esto? ¿Qué preocupaciones tendrías? ¿Cuánto pagarías de manera realista? ¿Qué necesitaría cambiar para que se convierta en un cliente? “

Los empresarios adolescentes a menudo luchan con la investigación de los clientes porque no pueden encuestar fácilmente a grandes grupos o contratar firmas de investigación de mercado. Este aviso ayuda a simular los comentarios de los clientes haciendo que ChatGPT adopte personas específicas.

Un adolescente que desarrolla un podcast para atletas adolescentes podría usar este enfoque pidiéndole a ChatGPT que responda a diferentes tipos de atletas adolescentes. Esto ayuda a identificar temas de contenido que resuenan y mensajes que se sienten auténticos para el público objetivo.

El aviso funciona mejor cuando se vuelve específico sobre la demografía, los puntos débiles y los contextos. “Actúa como un estudiante de último año de secundaria que solicita a la universidad” produce mejores ideas que “actuar como un adolescente”.

4. El mensaje mínimo de diseñador de prueba viable chatgpt

“Quiero probar esta idea de negocio: [describe concept] sin gastar más de [budget amount] o más de [time commitment]. Diseñe tres experimentos simples que podría ejecutar esta semana para validar la demanda de los clientes. Para cada prueba, explique lo que aprendería, cómo medir el éxito y qué resultados indicarían que debería avanzar “.

Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a adoptar la metodología Lean Startup sin perderse en la jerga comercial. El enfoque en “This Week” crea urgencia y evita la planificación interminable sin acción.

Un adolescente que desea probar un concepto de línea de ropa podría usar este indicador para diseñar experimentos de validación simples, como publicar maquetas de diseño en las redes sociales para evaluar el interés, crear un formulario de Google para recolectar pedidos anticipados y pedirles a los amigos que compartan el concepto con sus redes. Estas pruebas no cuestan nada más que proporcionar datos cruciales sobre la demanda y los precios.

5. El aviso de chatgpt del generador de claridad de tono

“Convierta esta idea de negocio en una clara explicación de 60 segundos: [describe your business]. La explicación debe incluir: el problema que resuelve, su solución, a quién ayuda, por qué lo elegirían sobre las alternativas y cómo se ve el éxito. Escríbelo en lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría “.

La comunicación clara separa a los empresarios exitosos de aquellos con buenas ideas pero una ejecución deficiente. Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a destilar conceptos complejos a explicaciones convincentes que pueden usar en todas partes, desde las publicaciones en las redes sociales hasta las conversaciones con posibles mentores.

El énfasis en el “lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría” es importante. Muchas plantillas de lanzamiento comercial suenan artificiales cuando se entregan jóvenes fundadores. La autenticidad es más importante que la jerga corporativa.

Más allá de las indicaciones de chatgpt: estrategia de implementación

La diferencia entre los adolescentes que usan estas indicaciones de manera efectiva y aquellos que no se reducen a seguir. ChatGPT proporciona dirección, pero la acción crea resultados.

Los jóvenes empresarios más exitosos con los que trabajo usan estas indicaciones como puntos de partida, no de punto final. Toman las sugerencias generadas por IA e inmediatamente las prueban en el mundo real. Llaman a clientes potenciales, crean prototipos simples e iteran en función de los comentarios reales.

Investigaciones recientes de Junior Achievement muestran que el 69% de los adolescentes tienen ideas de negocios, pero se sienten inciertos sobre el proceso de partida, con el miedo a que el fracaso sea la principal preocupación para el 67% de los posibles empresarios adolescentes. Estas indicaciones abordan esa incertidumbre al desactivar los conceptos abstractos en los próximos pasos concretos.

La imagen más grande

Los emprendedores adolescentes que utilizan herramientas de IA como ChatGPT representan un cambio en cómo está ocurriendo la educación empresarial. Según la investigación mundial de monitores empresariales, los jóvenes empresarios tienen 1,6 veces más probabilidades que los adultos de querer comenzar un negocio, y son particularmente activos en la tecnología, la alimentación y las bebidas, la moda y los sectores de entretenimiento. En lugar de esperar clases de emprendimiento formales o programas de MBA, estos jóvenes fundadores están accediendo a herramientas de pensamiento estratégico de inmediato.

Esta tendencia se alinea con cambios más amplios en la educación y la fuerza laboral. El Foro Económico Mundial identifica la creatividad, el pensamiento crítico y la resiliencia como las principales habilidades para 2025, la capacidad de las capacidades que el espíritu empresarial desarrolla naturalmente.

Programas como WIT brindan soporte estructurado para este viaje, pero las herramientas en sí mismas se están volviendo cada vez más accesibles. Un adolescente con acceso a Internet ahora puede acceder a recursos de planificación empresarial que anteriormente estaban disponibles solo para empresarios establecidos con presupuestos significativos.

La clave es usar estas herramientas cuidadosamente. ChatGPT puede acelerar el pensamiento y proporcionar marcos, pero no puede reemplazar el arduo trabajo de construir relaciones, crear productos y servir a los clientes. La mejor idea de negocio no es la más original, es la que resuelve un problema real para personas reales. Las herramientas de IA pueden ayudar a identificar esas oportunidades, pero solo la acción puede convertirlos en empresas que importan.

Noticias

Chatgpt vs. gemini: he probado ambos, y uno definitivamente es mejor

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Precio

ChatGPT y Gemini tienen versiones gratuitas que limitan su acceso a características y modelos. Los planes premium para ambos también comienzan en alrededor de $ 20 por mes. Las características de chatbot, como investigaciones profundas, generación de imágenes y videos, búsqueda web y más, son similares en ChatGPT y Gemini. Sin embargo, los planes de Gemini pagados también incluyen el almacenamiento en la nube de Google Drive (a partir de 2TB) y un conjunto robusto de integraciones en las aplicaciones de Google Workspace.

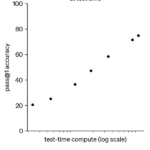

Los niveles de más alta gama de ChatGPT y Gemini desbloquean el aumento de los límites de uso y algunas características únicas, pero el costo mensual prohibitivo de estos planes (como $ 200 para Chatgpt Pro o $ 250 para Gemini Ai Ultra) los pone fuera del alcance de la mayoría de las personas. Las características específicas del plan Pro de ChatGPT, como el modo O1 Pro que aprovecha el poder de cálculo adicional para preguntas particularmente complicadas, no son especialmente relevantes para el consumidor promedio, por lo que no sentirá que se está perdiendo. Sin embargo, es probable que desee las características que son exclusivas del plan Ai Ultra de Gemini, como la generación de videos VEO 3.

Ganador: Géminis

Plataformas

Puede acceder a ChatGPT y Gemini en la web o a través de aplicaciones móviles (Android e iOS). ChatGPT también tiene aplicaciones de escritorio (macOS y Windows) y una extensión oficial para Google Chrome. Gemini no tiene aplicaciones de escritorio dedicadas o una extensión de Chrome, aunque se integra directamente con el navegador.

(Crédito: OpenAI/PCMAG)

Chatgpt está disponible en otros lugares, Como a través de Siri. Como se mencionó, puede acceder a Gemini en las aplicaciones de Google, como el calendario, Documento, ConducirGmail, Mapas, Mantener, FotosSábanas, y Música de YouTube. Tanto los modelos de Chatgpt como Gemini también aparecen en sitios como la perplejidad. Sin embargo, obtiene la mayor cantidad de funciones de estos chatbots en sus aplicaciones y portales web dedicados.

Las interfaces de ambos chatbots son en gran medida consistentes en todas las plataformas. Son fáciles de usar y no lo abruman con opciones y alternar. ChatGPT tiene algunas configuraciones más para jugar, como la capacidad de ajustar su personalidad, mientras que la profunda interfaz de investigación de Gemini hace un mejor uso de los bienes inmuebles de pantalla.

Ganador: empate

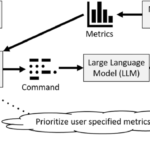

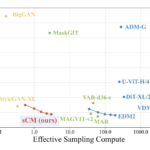

Modelos de IA

ChatGPT tiene dos series primarias de modelos, la serie 4 (su línea de conversación, insignia) y la Serie O (su compleja línea de razonamiento). Gemini ofrece de manera similar una serie Flash de uso general y una serie Pro para tareas más complicadas.

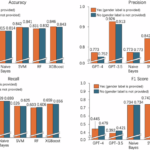

Los últimos modelos de Chatgpt son O3 y O4-Mini, y los últimos de Gemini son 2.5 Flash y 2.5 Pro. Fuera de la codificación o la resolución de una ecuación, pasará la mayor parte de su tiempo usando los modelos de la serie 4-Series y Flash. A continuación, puede ver cómo funcionan estos modelos en una variedad de tareas. Qué modelo es mejor depende realmente de lo que quieras hacer.

Ganador: empate

Búsqueda web

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden buscar información actualizada en la web con facilidad. Sin embargo, ChatGPT presenta mosaicos de artículos en la parte inferior de sus respuestas para una lectura adicional, tiene un excelente abastecimiento que facilita la vinculación de reclamos con evidencia, incluye imágenes en las respuestas cuando es relevante y, a menudo, proporciona más detalles en respuesta. Gemini no muestra nombres de fuente y títulos de artículos completos, e incluye mosaicos e imágenes de artículos solo cuando usa el modo AI de Google. El abastecimiento en este modo es aún menos robusto; Google relega las fuentes a los caretes que se pueden hacer clic que no resaltan las partes relevantes de su respuesta.

Como parte de sus experiencias de búsqueda en la web, ChatGPT y Gemini pueden ayudarlo a comprar. Si solicita consejos de compra, ambos presentan mosaicos haciendo clic en enlaces a los minoristas. Sin embargo, Gemini generalmente sugiere mejores productos y tiene una característica única en la que puede cargar una imagen tuya para probar digitalmente la ropa antes de comprar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Investigación profunda

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden generar informes que tienen docenas de páginas e incluyen más de 50 fuentes sobre cualquier tema. La mayor diferencia entre los dos se reduce al abastecimiento. Gemini a menudo cita más fuentes que CHATGPT, pero maneja el abastecimiento en informes de investigación profunda de la misma manera que lo hace en la búsqueda en modo AI, lo que significa caretas que se puede hacer clic sin destacados en el texto. Debido a que es más difícil conectar las afirmaciones en los informes de Géminis a fuentes reales, es más difícil creerles. El abastecimiento claro de ChatGPT con destacados en el texto es más fácil de confiar. Sin embargo, Gemini tiene algunas características de calidad de vida en ChatGPT, como la capacidad de exportar informes formateados correctamente a Google Docs con un solo clic. Su tono también es diferente. Los informes de ChatGPT se leen como publicaciones de foro elaboradas, mientras que los informes de Gemini se leen como documentos académicos.

Ganador: chatgpt

Generación de imágenes

La generación de imágenes de ChatGPT impresiona independientemente de lo que solicite, incluso las indicaciones complejas para paneles o diagramas cómicos. No es perfecto, pero los errores y la distorsión son mínimos. Gemini genera imágenes visualmente atractivas más rápido que ChatGPT, pero rutinariamente incluyen errores y distorsión notables. Con indicaciones complicadas, especialmente diagramas, Gemini produjo resultados sin sentido en las pruebas.

Arriba, puede ver cómo ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Géminis (segunda diapositiva) les fue con el siguiente mensaje: “Genere una imagen de un estudio de moda con una decoración simple y rústica que contrasta con el espacio más agradable. Incluya un sofá marrón y paredes de ladrillo”. La imagen de ChatGPT limita los problemas al detalle fino en las hojas de sus plantas y texto en su libro, mientras que la imagen de Gemini muestra problemas más notables en su tubo de cordón y lámpara.

Ganador: chatgpt

¡Obtenga nuestras mejores historias!

Toda la última tecnología, probada por nuestros expertos

Regístrese en el boletín de informes de laboratorio para recibir las últimas revisiones de productos de PCMAG, comprar asesoramiento e ideas.

Al hacer clic en Registrarme, confirma que tiene más de 16 años y acepta nuestros Términos de uso y Política de privacidad.

¡Gracias por registrarse!

Su suscripción ha sido confirmada. ¡Esté atento a su bandeja de entrada!

Generación de videos

La generación de videos de Gemini es la mejor de su clase, especialmente porque ChatGPT no puede igualar su capacidad para producir audio acompañante. Actualmente, Google bloquea el último modelo de generación de videos de Gemini, VEO 3, detrás del costoso plan AI Ultra, pero obtienes más videos realistas que con ChatGPT. Gemini también tiene otras características que ChatGPT no, como la herramienta Flow Filmmaker, que le permite extender los clips generados y el animador AI Whisk, que le permite animar imágenes fijas. Sin embargo, tenga en cuenta que incluso con VEO 3, aún necesita generar videos varias veces para obtener un gran resultado.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité a ChatGPT y Gemini a mostrarme un solucionador de cubos de Rubik Rubik que resuelva un cubo. La persona en el video de Géminis se ve muy bien, y el audio acompañante es competente. Al final, hay una buena atención al detalle con el marco que se desplaza, simulando la detención de una grabación de selfies. Mientras tanto, Chatgpt luchó con su cubo, distorsionándolo en gran medida.

Ganador: Géminis

Procesamiento de archivos

Comprender los archivos es una fortaleza de ChatGPT y Gemini. Ya sea que desee que respondan preguntas sobre un manual, editen un currículum o le informen algo sobre una imagen, ninguno decepciona. Sin embargo, ChatGPT tiene la ventaja sobre Gemini, ya que ofrece un reconocimiento de imagen ligeramente mejor y respuestas más detalladas cuando pregunta sobre los archivos cargados. Ambos chatbots todavía a veces inventan citas de documentos proporcionados o malinterpretan las imágenes, así que asegúrese de verificar sus resultados.

Ganador: chatgpt

Escritura creativa

Chatgpt y Gemini pueden generar poemas, obras, historias y más competentes. CHATGPT, sin embargo, se destaca entre los dos debido a cuán únicas son sus respuestas y qué tan bien responde a las indicaciones. Las respuestas de Gemini pueden sentirse repetitivas si no calibra cuidadosamente sus solicitudes, y no siempre sigue todas las instrucciones a la carta.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Gemini (segunda diapositiva) con lo siguiente: “Sin hacer referencia a nada en su memoria o respuestas anteriores, quiero que me escriba un poema de verso gratuito. Preste atención especial a la capitalización, enjambment, ruptura de línea y puntuación. Dado que es un verso libre, no quiero un medidor familiar o un esquema de retiro de la rima, pero quiero que tenga un estilo de coohes. ChatGPT logró entregar lo que pedí en el aviso, y eso era distinto de las generaciones anteriores. Gemini tuvo problemas para generar un poema que incorporó cualquier cosa más allá de las comas y los períodos, y su poema anterior se lee de manera muy similar a un poema que generó antes.

Recomendado por nuestros editores

Ganador: chatgpt

Razonamiento complejo

Los modelos de razonamiento complejos de Chatgpt y Gemini pueden manejar preguntas de informática, matemáticas y física con facilidad, así como mostrar de manera competente su trabajo. En las pruebas, ChatGPT dio respuestas correctas un poco más a menudo que Gemini, pero su rendimiento es bastante similar. Ambos chatbots pueden y le darán respuestas incorrectas, por lo que verificar su trabajo aún es vital si está haciendo algo importante o tratando de aprender un concepto.

Ganador: chatgpt

Integración

ChatGPT no tiene integraciones significativas, mientras que las integraciones de Gemini son una característica definitoria. Ya sea que desee obtener ayuda para editar un ensayo en Google Docs, comparta una pestaña Chrome para hacer una pregunta, pruebe una nueva lista de reproducción de música de YouTube personalizada para su gusto o desbloquee ideas personales en Gmail, Gemini puede hacer todo y mucho más. Es difícil subestimar cuán integrales y poderosas son realmente las integraciones de Géminis.

Ganador: Géminis

Asistentes de IA

ChatGPT tiene GPT personalizados, y Gemini tiene gemas. Ambos son asistentes de IA personalizables. Tampoco es una gran actualización sobre hablar directamente con los chatbots, pero los GPT personalizados de terceros agregan una nueva funcionalidad, como el fácil acceso a Canva para editar imágenes generadas. Mientras tanto, terceros no pueden crear gemas, y no puedes compartirlas. Puede permitir que los GPT personalizados accedan a la información externa o tomen acciones externas, pero las GEM no tienen una funcionalidad similar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Contexto Windows y límites de uso

La ventana de contexto de ChatGPT sube a 128,000 tokens en sus planes de nivel superior, y todos los planes tienen límites de uso dinámicos basados en la carga del servidor. Géminis, por otro lado, tiene una ventana de contexto de 1,000,000 token. Google no está demasiado claro en los límites de uso exactos para Gemini, pero también son dinámicos dependiendo de la carga del servidor. Anecdóticamente, no pude alcanzar los límites de uso usando los planes pagados de Chatgpt o Gemini, pero es mucho más fácil hacerlo con los planes gratuitos.

Ganador: Géminis

Privacidad

La privacidad en Chatgpt y Gemini es una bolsa mixta. Ambos recopilan cantidades significativas de datos, incluidos todos sus chats, y usan esos datos para capacitar a sus modelos de IA de forma predeterminada. Sin embargo, ambos le dan la opción de apagar el entrenamiento. Google al menos no recopila y usa datos de Gemini para fines de capacitación en aplicaciones de espacio de trabajo, como Gmail, de forma predeterminada. ChatGPT y Gemini también prometen no vender sus datos o usarlos para la orientación de anuncios, pero Google y OpenAI tienen historias sórdidas cuando se trata de hacks, filtraciones y diversos fechorías digitales, por lo que recomiendo no compartir nada demasiado sensible.

Ganador: empate

Related posts

Trending

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoRemove.bg: La Revolución en la Edición de Imágenes que Debes Conocer

-

Tutoriales2 años ago

Tutoriales2 años agoCómo Comenzar a Utilizar ChatGPT: Una Guía Completa para Principiantes

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoStartups de IA en EE.UU. que han recaudado más de $100M en 2024

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoDeepgram: Revolucionando el Reconocimiento de Voz con IA

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoCómo Empezar con Popai.pro: Tu Espacio Personal de IA – Guía Completa, Instalación, Versiones y Precios

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoPerplexity aplicado al Marketing Digital y Estrategias SEO

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial Aplicada de 4Geeks Academy 2024

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial de UC Berkeley estratégico para negocios