When it was founded in 2015, artificial intelligence research lab OpenAI was a nonprofit organization. The idealistic mission: to make sure the high-stakes work they were doing on artificial intelligence served the whole world. This was necessary because — according to the founders’ fervent belief, at least — it would transform the whole world.

Noticias

OpenAI is transitioning to a for-profit business. The stakes are enormous.

Published

1 año agoon

In some ways since then, OpenAI has succeeded beyond its wildest dreams. “General artificial intelligence” sounded like a pipe dream in 2015, but today we have talking, interactive, creative AI that can pass most tests of human competence we’ve put it to. Many serious people believe that full general intelligence is just around the corner. OpenAI, which in the years since its founding morphed from a nonprofit lab into one of the most highly valued startups in history, has been at the center of that transformation. (Disclosure: Vox Media is one of several publishers that has signed partnership agreements with OpenAI. Our reporting remains editorially independent.)

In other ways, of course, things have been a bit of a mess. Even as it basically became a business, OpenAI used nonprofit governance to keep the company focused on its mission. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman reassured Congress he had no equity in the company, and the nonprofit board still held all authority to change course if they thought the company had gone astray from its mission.

But that ultimately put the board at odds with Altman last November in a messy conflict that the CEO ultimately won. Nearly the entire original leadership team departed. In the year since, the board has largely been replaced and high-profile employees have left the company in waves, some of them warning they no longer believe OpenAI will build superintelligence responsibly. Microsoft, OpenAI’s largest investor, increasingly seems eager for the company to stop building superintelligence and start building a profitable product.

Now, OpenAI is attempting a transition to a more conventional corporate structure, reportedly one where it will be a for-profit public benefit corporation like its rival Anthropic. But nonprofit to for-profit conversions are rare, and misinformation has swirled about what, exactly, “OpenAI becoming a for-profit company” even means.

Elon Musk, who co-founded OpenAI but left after a leadership dispute, paints the for-profit transition as a naked power grab, arguing in a recent lawsuit that Altman and his associates “systematically drained the non-profit of its valuable technology and personnel” in a scheme to get rich off a company that had been founded as a charity. (OpenAI has moved to dismiss Musk’s lawsuit, arguing that it is an “increasingly blusterous campaign to harass OpenAI for his own competitive advantage”).

While Musk — who has his own reasons to be competitive with OpenAI — is among the more vocal critics, many people seem to be under the impression that the company could just slap on a new “for-profit” label and call it a day.

Can you really do that? Start a charity, with all the advantages of nonprofit status, and then declare one day it’s a for-profit company? No, you can’t, and it’s important to understand that OpenAI isn’t doing that.

Rather, nonprofit lawyers told me that what’s almost certainly going on is a complicated and fraught negotiation: the sale of all of the OpenAI nonprofit’s valuable assets to the new for-profit entity, in exchange for the nonprofit continuing to exist and becoming a major investor in the new for-profit entity.

The key question is how much are those assets worth, and can the battered and bruised nonprofit board get a fair deal out of OpenAI (and Microsoft)?

So far, this high-stakes wrangling has taken place almost entirely behind the scenes, and many of the crucial questions have gotten barely any public coverage at all. “I’ve been really kind of baffled at the lack of curiosity about where the value goes that this nonprofit has,” nonprofit law expert Timothy Ogden told me.

Nonprofit law might seem abstruse, which is why most coverage of OpenAI’s transition hasn’t dug into any of the messy details. But those messy details involve tens of billions of dollars, all of which appear to be up for negotiation. The results will dramatically affect how much sway Microsoft has with OpenAI going forward and how much of the company’s value is still tied to its founding mission.

This might seem like something that only matters for OpenAI shareholders, but the company is one of the few that may just have a chance of creating world-changing artificial intelligence. If the public wants a transparent and open process from OpenAI, they have to understand what the law actually allows and who is responsible for following it so we can be sure that OpenAI pursues this transition in a transparent and accountable way.

How OpenAI went from nonprofit to megacorp

In 2015, OpenAI was a nonprofit research organization. It told the IRS in a filing for nonprofit status that its mission was to “advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return.”

Understanding OpenAI’s expansive reach

OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, is one of the most important companies in artificial intelligence and one of the most controversial. I’ve been covering the ins and outs of OpenAI for years; here are some highlights:

Have questions or comments? Email me at [email protected].

By 2019, that idealistic nonprofit model was running into some trouble. OpenAI had attracted an incredible staff and published some very impressive research. But it was becoming clear that the lofty goal the company had set itself — building general artificial intelligence, machines that can do everything humans can do — was going to be very expensive. It was naturally hard to raise billions of dollars for an effort that was meant to be nonprofit. “We realized that we’d reached the limits of our fundraising ability as a pure nonprofit,” co-founder Ilya Sutskever (who has since departed the company) told me at the time.

The company would attempt to split the difference with a hybrid structure: a nonprofit board controlling a for-profit company. An additional twist: Investors in the for-profit company’s returns were capped at 100x their original investments so that, if world-altering superintelligence was achieved as the OpenAI leadership believed it might, the benefits would accrue to all humanity and not just investors. After all, investors needed to be enticed to invest, but if the company truly ended material scarcity and built a God on Earth, as they essentially said they wanted to, the hope was that more than just the investors would come out ahead.

The nonprofit, therefore, was still supposed to be preeminent. “It would be wise to view any investment in OpenAI Global, LLC in the spirit of a donation,” an enormous black-and-pink disclaimer box on OpenAI’s website alerts would-be investors, “with the understanding that it may be difficult to know what role money will play in a post-AGI world. The Company exists to advance OpenAl, Inc.‘s mission of ensuring that safe artificial general intelligence is developed and benefits all of humanity. The Company’s duty to this mission and the principles advanced in the OpenAl, Inc. Charter take precedence over any obligation to generate a profit.”

One might expect that a prominent disclaimer like that would give commercial investors pause. You would be mistaken. OpenAI had Altman, a fantastic fundraiser, at the helm; its flagship product, ChatGPT, was the fastest app to 100 million users. The company was a gamble, but it was the kind of gamble investors can’t wait to get in on.

But that was then, and this is now. In 2023, in an unexpected and disastrously under-explained move, the nonprofit board fired OpenAI CEO Sam Altman. The board had that authority, of course — it was preeminent — but the execution was shockingly clumsy. The timing of the firing looked likely to disrupt an opportunity for employees to sell millions of dollars of stock in the company. The board gave a few examples of underhanded, bizarre, and dishonest behavior by Altman, including being “not consistently candid” with the board. (One board member later expanded the allegations, saying that Altman had lied to board members about private conversations with other board members, but provided nothing as clear as confused and frustrated employees hoped.)

Employees threatened to resign en masse. Microsoft offered to hire them all and reconstitute the company. Sutskever, who was among the board members who’d voted for Altman’s removal, suddenly changed his mind and voted for Altman to stay. That meant the members who had fired Altman were suddenly in the minority. Two of the board members who had opposed Altman resigned, and the once and future CEO returned to the helm.

Many people concluded that it had been a serious mistake to try to run a company worth 11 figures as a nonprofit instead of as the decidedly for-profit company it was clearly operating as, whatever its bylaws might say. So it’s not surprising that ever since the aborted Altman coup, rumors swirled that OpenAI meant to transition to a fully for-profit entity.

In the last few weeks, those rumors have gotten much more concrete. OpenAI’s latest funding round has been reported to include commitments that the nonprofit-to-for-profit transition will get done in the next two years on pain of the more than $6 billion raised being paid back to those investors. Microsoft and OpenAI — both of whom have enormous amounts to gain in the wrangling over who owns the resulting for-profit company — have hired dueling investment banks to negotiate the details.

We are moving into a new era for OpenAI, and it remains to be seen what that will mean for the humble nonprofit that has ended up owning tens of billions of dollars of the company’s assets.

How do you turn a charity into a for-profit?

If OpenAI were really just taking the nonprofit organization’s assets and declaring them “converted” into a for-profit — as if they were playing a game of tag and suddenly decided a tree was “base” — that would absolutely be illegal. The takeaway, though, shouldn’t be that a crime is happening in plain sight, but that something much more complicated is being negotiated. Nonprofit law experts I talked to said that the situation was being widely and comprehensively misunderstood.

Here are the rules. First off, assets accumulated by a nonprofit cannot be used for private benefit. “It’s the job of the board first, and then the regulators and the court, to ensure that the promise that was made to the public to pursue the charitable interest is kept,” UCLA law professor Jill Horwitz told Reuters.

If it looks as though a nonprofit isn’t pursuing its charitable interest, and especially if it appears to be handing some of its board members bargain-bin deals on billion-dollar assets during a transition to for-profit status? That will have the IRS investigating, along with the state’s Attorney General.

But a nonprofit can sell anything it owns. If a nonprofit owns a piece of land, for example, and it wants to sell that land so that it has more money to spend on its mission, it’s all good. If the nonprofit sold the land for well below market value to the director’s nephew, it would be a clear crime, and the IRS or the state’s Attorney General might well investigate. The nonprofit has to sell the land at a fair market price, take the money, and keep using the money for its nonprofit work.

At a much larger scale, that is exactly what is at stake in the OpenAI transition. The nonprofit owns some assets: control over the for-profit company, a lot of AI IP from OpenAI’s proprietary research, and all future returns from the for-profit company once they exceed the 100x cap set up by the capped profit company — which, should the company achieve its goals, could well be limitless. If the new OpenAI wants to extract all of its assets from the nonprofit, it has to pay the full market price. And the nonprofit has to continue to exist and to use the money it has earned in that transfer for its mission of ensuring that AI benefits all of humanity.

There have been a few other cases in corporate legal history of a nonprofit making the transition to a for-profit company, most prominently the credit card company Mastercard, which was founded as a nonprofit collaboration among banks. When that situation happens, the nonprofit’s assets still belong to the nonprofit.

Mastercard, in the course of transitioning to a public company, ended up founding the now-$47 billion Mastercard Foundation, one of the world’s wealthiest private foundations. Far from the for-profit walking away with all the nonprofit’s assets, the for-profit emerges as an independent company and the nonprofit emerges not only still extant but very rich.

OpenAI’s board has indicated that this is exactly what they are doing. “Any potential restructuring would ensure the nonprofit continues to exist and thrive, and receives full value for its current stake in the OpenAI for-profit with an enhanced ability to pursue its mission.” OpenAI board chairman Bret Taylor, a technologist and CEO, told me in a statement. (What counts as “full value”? We’ll come back to that.)

Outside actors, too, expect to be applying oversight to make sure that the nonprofit gets a fair deal. A spokesperson for the California Attorney General’s office told the Information that their office is “committed to protecting charitable assets for their intended purpose.” OpenAI is registered in Delaware, but the company operates primarily in California, and California’s AG is much less deferential to business than Delaware’s.

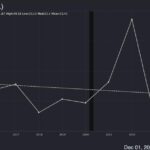

So, the OpenAI entity will definitely owe the nonprofit mind-boggling amounts of money. Depending who you ask, it could be between $37 billion and $80 billion. The OpenAI for-profit entity does not have that kind of money on hand — don’t forget that OpenAI is projected to lose tens of billions of dollars in the years ahead — so the plans in the works are reportedly for the for-profit to make the nonprofit a major shareholder in the for-profit.

The Information reported last week that “the nonprofit is expected to own at least a 25% stake in the for-profit — which on paper would be worth at least $37 billion.” In other words, rather than buying the assets from the non-profit with cash, OpenAI will trade equity.

That’s a lot of money. But many experts I spoke to thought it was actually much too low.

What’s a fair price for control of a mega company?

Everyone agrees that the OpenAI board is required to negotiate and receive a fair price for everything the OpenAI nonprofit owns that the for-profit is purchasing. But what counts as a fair price? That’s an open question, one that people stand to earn or lose tens of billions of dollars by getting answered in their favor.

But first: What does the OpenAI nonprofit own?

It owns a lot of OpenAI’s IP. How much exactly is highly confidential, but some experts speculate that the $37 billion number is probably a reflection of the easily measured, straightforward assets of the nonprofit, like its IP and business agreements.

Secondly, and most crucially, it owns full control over the OpenAI for-profit. As part of this deal, it is definitely going to give that up, either becoming a minority shareholder or ending up with nonvoting shares entirely. That is, substantially, the whole point of the nonprofit-to-for-profit conversion: After Altman’s ouster, the Wall Street Journal reported, “[I]nvestors began pushing OpenAI to turn into a more typical company.” Investors throwing around billions of dollars don’t want a nonprofit board to be able to fire the CEO because they’re worried he’s too dishonest to make good decisions around powerful new technology. Investors want a normal board that will fire the CEO for normal reasons, like that he’s not maximizing shareholder value.

Control is generally worth a lot more, in for-profit companies, than shares that come without control — often something like 40 percent more. So if the nonprofit is getting a fair deal, it should get some substantive compensation in exchange for giving up control of the company.

Thirdly, investors in OpenAI under its old business model agreed to a “capped profit” model. For most investors, that cap was set at 100x their original investment, so if they invested $1 million, they would get a maximum of $100 million in return. Above that cap, all returns would go to the nonprofit. The logic for this setup was that, under most circumstances, it’s the same as investing in a normal company. Investments don’t usually produce 100x returns, after all, with the exception of early investments in massively successful tech companies like Google or Amazon.

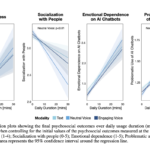

The capped profit setup would be most significant in the unlikely world where OpenAI attained its ambitious goals and built an AI that fundamentally transformed the world economy. (How likely is that? Experts disagree, rather heatedly, but we shouldn’t discount it altogether.) If that does happen, its value will be nearly unfathomably huge. “OpenAI’s value is mostly in the extreme upside,” AI analyst Zvi Mowshowitz wrote in an analysis of the valuation question.

The company might fail entirely; it might muddle along as a midsized company. But it also might be worth trillions of dollars, or more than that, and most investors are investing on the premise it might be worth trillions of dollars. That means the share of profits owned by the nonprofit would also be worth trillions of dollars. “Most future profits still likely flow to the nonprofit,” Mowshowitz concludes. “OpenAI is shooting for the stars. As every VC in this spot knows, it is the extreme upside that matters. That is what the nonprofit is selling. They shouldn’t sell it cheap.”

So what would be an appropriate valuation? $60 billion? $100 billion? Mowshowitz’s analysis is that a fair price would involve the nonprofit still owning a majority of shares in the for-profit, which is to say at least $80 billion. (Presumably these would be nonvoting shares.)

The only people with full information are the ones with access to the company’s confidential balance sheets, and they aren’t talking. OpenAI and Microsoft will be negotiating the answer to the question, but it’s not clear that either of them particularly wants the nonprofit to get a valuation that reflects, for example, the expected value of the profits in excess of the cap because there’s more money for everyone else who wants a piece of the pie if the nonprofit gets less.

There are two forces working toward the nonprofit getting fair compensation: the nonprofit board — whose members are capable people, but also people handpicked by Altman not to get ideas and get in the way of his control of the company — and the law. Experts I spoke with were a bit cynical about the board’s willingness to hold out for a good deal in what is an extremely awkward circumstance for it. “We have kind of already seen what’s going on with the OpenAI board,” Ogden told me.

“I think the common understanding is they’re friendly to Sam Altman, and the ones who were trying to slow things down or protect the nonprofit purpose have left,” Rose Chan Loui, the director of UCLA Law’s nonprofit program, observed to the Transformer.

If the board is inclined to go with the flow, the Delaware Attorney General or the IRS could object. These are fundamentally complicated questions about the valuation of a private company, and the law isn’t always good at consistent and principled enforcement in cases like this one. “When you’re talking about numbers like $150 billion,” UCLA law professor Jill Horwitz warned, “the law has a way of getting weak.”

Does that mean that Elon Musk’s allegation — that we’re witnessing a bait-and-switch before our eyes, a massive theft of resources that were originally dedicated to the common good — is right after all? I’m not inclined to grant him that much.

Firstly, having spoken to OpenAI leadership and OpenAI employees over the six years I’ve been reporting on the company, I genuinely come away with the impression that the bait-and-switch, to the extent it happened, was completely unintentional.

In 2015, the involved parties really were — including in private emails leaked in Musk’s lawsuits — convinced that a research organization serving the public was the way to achieve their mission. And then over the next few years, as the power of big machine learning models became apparent, they became sincerely convinced they needed to find clever ways to raise money for their research. In 2019, when I spoke with Brockman and Sutskever, they were enthusiastic about their capped profit structure and saw it as a model for how a company could raise money but ensure most of its benefits if it succeeded went to humanity as a whole.

Altman has a habit of being all things to all people, even when that may require being less than truthful. His detractors say he’s “deceptive, manipulative, and worse”, and even his supporters will say he’s “extremely good at becoming powerful,” which VCs might consider more of a compliment than the general public does.

But I don’t think Altman was aiming for this predicament. OpenAI did not inflict its current legal headache on itself out of cunning chicanery, but out of a desire to satisfy a number of different early stakeholders, many of them true believers. It was due chiefly to understandable failures of foresight about how much power corporate governance law would really have once employees had millions riding on the company’s continued fundraising and once investors had billions riding on its ability to make a profit.

Secondly, I think it’s far too soon to call this a bait-and-switch. The nonprofit’s control of OpenAI was meant to give it the power to stop the company from putting profits before the mission. But it turns out that being on a nonprofit board does not come with enough access to the company, or enough real power, to productively turn OpenAI away from the brink, as we discovered last November.

It seems entirely possible that a massive and highly capitalized nonprofit foundation with the aim of ensuring AI benefits humanity is a better approach than a corporate governance agreement with power on paper and none in practice. If the nonprofit gets massively undervalued in the conversion and shooed away with a quarter of the company when more careful estimates suggest it currently controls a majority of the company’s value, then we can call it a bait-and-switch.

But that hasn’t happened. The correct attitude is to wait and see, to demand transparency, to hold the board to account for getting the valuation it is legally obligated to pursue, and to pursue OpenAI to the full extent of the law if it ends up convincing the board to give up its extraordinary bequest at bargain-basement prices.

You may like

Noticias

Revivir el compromiso en el aula de español: un desafío musical con chatgpt – enfoque de la facultad

Published

8 meses agoon

6 junio, 2025

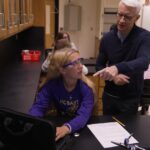

A mitad del semestre, no es raro notar un cambio en los niveles de energía de sus alumnos (Baghurst y Kelley, 2013; Kumari et al., 2021). El entusiasmo inicial por aprender un idioma extranjero puede disminuir a medida que otros cursos con tareas exigentes compitan por su atención. Algunos estudiantes priorizan las materias que perciben como más directamente vinculadas a su especialidad o carrera, mientras que otros simplemente sienten el peso del agotamiento de mediados de semestre. En la primavera, los largos meses de invierno pueden aumentar esta fatiga, lo que hace que sea aún más difícil mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos (Rohan y Sigmon, 2000).

Este es el momento en que un instructor de idiomas debe pivotar, cambiando la dinámica del aula para reavivar la curiosidad y la motivación. Aunque los instructores se esfuerzan por incorporar actividades que se adapten a los cinco estilos de aprendizaje preferidos (Felder y Henriques, 1995)-Visual (aprendizaje a través de imágenes y comprensión espacial), auditivo (aprendizaje a través de la escucha y discusión), lectura/escritura (aprendizaje a través de interacción basada en texto), Kinesthetic (aprendizaje a través de movimiento y actividades prácticas) y multimodal (una combinación de múltiples estilos)-its is beneficiales). Estructurado y, después de un tiempo, clases predecibles con actividades que rompen el molde. La introducción de algo inesperado y diferente de la dinámica del aula establecida puede revitalizar a los estudiantes, fomentar la creatividad y mejorar su entusiasmo por el aprendizaje.

La música, en particular, ha sido durante mucho tiempo un aliado de instructores que enseñan un segundo idioma (L2), un idioma aprendido después de la lengua nativa, especialmente desde que el campo hizo la transición hacia un enfoque más comunicativo. Arraigado en la interacción y la aplicación del mundo real, el enfoque comunicativo prioriza el compromiso significativo sobre la memorización de memoria, ayudando a los estudiantes a desarrollar fluidez de formas naturales e inmersivas. La investigación ha destacado constantemente los beneficios de la música en la adquisición de L2, desde mejorar la pronunciación y las habilidades de escucha hasta mejorar la retención de vocabulario y la comprensión cultural (DeGrave, 2019; Kumar et al. 2022; Nuessel y Marshall, 2008; Vidal y Nordgren, 2024).

Sobre la base de esta tradición, la actividad que compartiremos aquí no solo incorpora música sino que también integra inteligencia artificial, agregando una nueva capa de compromiso y pensamiento crítico. Al usar la IA como herramienta en el proceso de aprendizaje, los estudiantes no solo se familiarizan con sus capacidades, sino que también desarrollan la capacidad de evaluar críticamente el contenido que genera. Este enfoque los alienta a reflexionar sobre el lenguaje, el significado y la interpretación mientras participan en el análisis de texto, la escritura creativa, la oratoria y la gamificación, todo dentro de un marco interactivo y culturalmente rico.

Descripción de la actividad: Desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre”

Objetivo:

Los estudiantes mejorarán su comprensión auditiva y su producción escrita en español analizando y recreando letras de canciones con la ayuda de ChatGPT. Si bien las instrucciones se presentan aquí en inglés, la actividad debe realizarse en el idioma de destino, ya sea que se enseñe el español u otro idioma.

Instrucciones:

1. Escuche y decodifique

- Divida la clase en grupos de 2-3 estudiantes.

- Elija una canción en español (por ejemplo, La Llorona por chavela vargas, Oye CÓMO VA por Tito Puente, Vivir mi Vida por Marc Anthony).

- Proporcione a cada grupo una versión incompleta de la letra con palabras faltantes.

- Los estudiantes escuchan la canción y completan los espacios en blanco.

2. Interpretar y discutir

- Dentro de sus grupos, los estudiantes analizan el significado de la canción.

- Discuten lo que creen que transmiten las letras, incluidas las emociones, los temas y cualquier referencia cultural que reconocan.

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- ¿Puedes identificar alguna referencia cultural en la canción? ¿Cómo dan forma a su significado?

- ¿Cómo influye la música (melodía, ritmo, etc.) en su interpretación de la letra?

- Cada grupo comparte su interpretación con la clase.

3. Comparar con chatgpt

- Después de formar su propio análisis, los estudiantes preguntan a Chatgpt:

- ¿Qué crees que la canción está tratando de comunicarse?

- ¿Qué emociones o sentimientos evocan las letras para ti?

- Comparan la interpretación de ChatGPT con sus propias ideas y discuten similitudes o diferencias.

4. Crea tu propio verso

- Cada grupo escribe un nuevo verso que coincide con el estilo y el ritmo de la canción.

- Pueden pedirle ayuda a ChatGPT: “Ayúdanos a escribir un nuevo verso para esta canción con el mismo estilo”.

5. Realizar y cantar

- Cada grupo presenta su nuevo verso a la clase.

- Si se sienten cómodos, pueden cantarlo usando la melodía original.

- Es beneficioso que el profesor tenga una versión de karaoke (instrumental) de la canción disponible para que las letras de los estudiantes se puedan escuchar claramente.

- Mostrar las nuevas letras en un monitor o proyector permite que otros estudiantes sigan y canten juntos, mejorando la experiencia colectiva.

6. Elección – El Grammy va a

Los estudiantes votan por diferentes categorías, incluyendo:

- Mejor adaptación

- Mejor reflexión

- Mejor rendimiento

- Mejor actitud

- Mejor colaboración

7. Reflexión final

- ¿Cuál fue la parte más desafiante de comprender la letra?

- ¿Cómo ayudó ChatGPT a interpretar la canción?

- ¿Qué nuevas palabras o expresiones aprendiste?

Pensamientos finales: música, IA y pensamiento crítico

Un desafío musical con Chatgpt: “Canta y descubre” (Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt: “Cantar y Descubrir”) es una actividad que he encontrado que es especialmente efectiva en mis cursos intermedios y avanzados. Lo uso cuando los estudiantes se sienten abrumados o distraídos, a menudo alrededor de los exámenes parciales, como una forma de ayudarlos a relajarse y reconectarse con el material. Sirve como un descanso refrescante, lo que permite a los estudiantes alejarse del estrés de las tareas y reenfocarse de una manera divertida e interactiva. Al incorporar música, creatividad y tecnología, mantenemos a los estudiantes presentes en la clase, incluso cuando todo lo demás parece exigir su atención.

Más allá de ofrecer una pausa bien merecida, esta actividad provoca discusiones atractivas sobre la interpretación del lenguaje, el contexto cultural y el papel de la IA en la educación. A medida que los estudiantes comparan sus propias interpretaciones de las letras de las canciones con las generadas por ChatGPT, comienzan a reconocer tanto el valor como las limitaciones de la IA. Estas ideas fomentan el pensamiento crítico, ayudándoles a desarrollar un enfoque más maduro de la tecnología y su impacto en su aprendizaje.

Agregar el elemento de karaoke mejora aún más la experiencia, dando a los estudiantes la oportunidad de realizar sus nuevos versos y divertirse mientras practica sus habilidades lingüísticas. Mostrar la letra en una pantalla hace que la actividad sea más inclusiva, lo que permite a todos seguirlo. Para hacerlo aún más agradable, seleccionando canciones que resuenen con los gustos de los estudiantes, ya sea un clásico como La Llorona O un éxito contemporáneo de artistas como Bad Bunny, Selena, Daddy Yankee o Karol G, hace que la actividad se sienta más personal y atractiva.

Esta actividad no se limita solo al aula. Es una gran adición a los clubes españoles o eventos especiales, donde los estudiantes pueden unirse a un amor compartido por la música mientras practican sus habilidades lingüísticas. Después de todo, ¿quién no disfruta de una buena parodia de su canción favorita?

Mezclar el aprendizaje de idiomas con música y tecnología, Desafío Musical Con Chatgpt Crea un entorno dinámico e interactivo que revitaliza a los estudiantes y profundiza su conexión con el lenguaje y el papel evolutivo de la IA. Convierte los momentos de agotamiento en oportunidades de creatividad, exploración cultural y entusiasmo renovado por el aprendizaje.

Angela Rodríguez Mooney, PhD, es profesora asistente de español y la Universidad de Mujeres de Texas.

Referencias

Baghurst, Timothy y Betty C. Kelley. “Un examen del estrés en los estudiantes universitarios en el transcurso de un semestre”. Práctica de promoción de la salud 15, no. 3 (2014): 438-447.

DeGrave, Pauline. “Música en el aula de idiomas extranjeros: cómo y por qué”. Revista de Enseñanza e Investigación de Lenguas 10, no. 3 (2019): 412-420.

Felder, Richard M. y Eunice R. Henriques. “Estilos de aprendizaje y enseñanza en la educación extranjera y de segundo idioma”. Anales de idiomas extranjeros 28, no. 1 (1995): 21-31.

Nuessel, Frank y April D. Marshall. “Prácticas y principios para involucrar a los tres modos comunicativos en español a través de canciones y música”. Hispania (2008): 139-146.

Kumar, Tribhuwan, Shamim Akhter, Mehrunnisa M. Yunus y Atefeh Shamsy. “Uso de la música y las canciones como herramientas pedagógicas en la enseñanza del inglés como contextos de idiomas extranjeros”. Education Research International 2022, no. 1 (2022): 1-9

Noticias

5 indicaciones de chatgpt que pueden ayudar a los adolescentes a lanzar una startup

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Teen emprendedor que usa chatgpt para ayudarlo con su negocio

El emprendimiento adolescente sigue en aumento. Según Junior Achievement Research, el 66% de los adolescentes estadounidenses de entre 13 y 17 años dicen que es probable que considere comenzar un negocio como adultos, con el monitor de emprendimiento global 2023-2024 que encuentra que el 24% de los jóvenes de 18 a 24 años son actualmente empresarios. Estos jóvenes fundadores no son solo soñando, están construyendo empresas reales que generan ingresos y crean un impacto social, y están utilizando las indicaciones de ChatGPT para ayudarlos.

En Wit (lo que sea necesario), la organización que fundó en 2009, hemos trabajado con más de 10,000 jóvenes empresarios. Durante el año pasado, he observado un cambio en cómo los adolescentes abordan la planificación comercial. Con nuestra orientación, están utilizando herramientas de IA como ChatGPT, no como atajos, sino como socios de pensamiento estratégico para aclarar ideas, probar conceptos y acelerar la ejecución.

Los emprendedores adolescentes más exitosos han descubierto indicaciones específicas que los ayudan a pasar de una idea a otra. Estas no son sesiones genéricas de lluvia de ideas: están utilizando preguntas específicas que abordan los desafíos únicos que enfrentan los jóvenes fundadores: recursos limitados, compromisos escolares y la necesidad de demostrar sus conceptos rápidamente.

Aquí hay cinco indicaciones de ChatGPT que ayudan constantemente a los emprendedores adolescentes a construir negocios que importan.

1. El problema del primer descubrimiento chatgpt aviso

“Me doy cuenta de que [specific group of people]

luchar contra [specific problem I’ve observed]. Ayúdame a entender mejor este problema explicando: 1) por qué existe este problema, 2) qué soluciones existen actualmente y por qué son insuficientes, 3) cuánto las personas podrían pagar para resolver esto, y 4) tres formas específicas en que podría probar si este es un problema real que vale la pena resolver “.

Un adolescente podría usar este aviso después de notar que los estudiantes en la escuela luchan por pagar el almuerzo. En lugar de asumir que entienden el alcance completo, podrían pedirle a ChatGPT que investigue la deuda del almuerzo escolar como un problema sistémico. Esta investigación puede llevarlos a crear un negocio basado en productos donde los ingresos ayuden a pagar la deuda del almuerzo, lo que combina ganancias con el propósito.

Los adolescentes notan problemas de manera diferente a los adultos porque experimentan frustraciones únicas, desde los desafíos de las organizaciones escolares hasta las redes sociales hasta las preocupaciones ambientales. Según la investigación de Square sobre empresarios de la Generación de la Generación Z, el 84% planea ser dueños de negocios dentro de cinco años, lo que los convierte en candidatos ideales para las empresas de resolución de problemas.

2. El aviso de chatgpt de chatgpt de chatgpt de realidad de la realidad del recurso

“Soy [age] años con aproximadamente [dollar amount] invertir y [number] Horas por semana disponibles entre la escuela y otros compromisos. Según estas limitaciones, ¿cuáles son tres modelos de negocio que podría lanzar de manera realista este verano? Para cada opción, incluya costos de inicio, requisitos de tiempo y los primeros tres pasos para comenzar “.

Este aviso se dirige al elefante en la sala: la mayoría de los empresarios adolescentes tienen dinero y tiempo limitados. Cuando un empresario de 16 años emplea este enfoque para evaluar un concepto de negocio de tarjetas de felicitación, puede descubrir que pueden comenzar con $ 200 y escalar gradualmente. Al ser realistas sobre las limitaciones por adelantado, evitan el exceso de compromiso y pueden construir hacia objetivos de ingresos sostenibles.

Según el informe de Gen Z de Square, el 45% de los jóvenes empresarios usan sus ahorros para iniciar negocios, con el 80% de lanzamiento en línea o con un componente móvil. Estos datos respaldan la efectividad de la planificación basada en restricciones: cuando funcionan los adolescentes dentro de las limitaciones realistas, crean modelos comerciales más sostenibles.

3. El aviso de chatgpt del simulador de voz del cliente

“Actúa como un [specific demographic] Y dame comentarios honestos sobre esta idea de negocio: [describe your concept]. ¿Qué te excitaría de esto? ¿Qué preocupaciones tendrías? ¿Cuánto pagarías de manera realista? ¿Qué necesitaría cambiar para que se convierta en un cliente? “

Los empresarios adolescentes a menudo luchan con la investigación de los clientes porque no pueden encuestar fácilmente a grandes grupos o contratar firmas de investigación de mercado. Este aviso ayuda a simular los comentarios de los clientes haciendo que ChatGPT adopte personas específicas.

Un adolescente que desarrolla un podcast para atletas adolescentes podría usar este enfoque pidiéndole a ChatGPT que responda a diferentes tipos de atletas adolescentes. Esto ayuda a identificar temas de contenido que resuenan y mensajes que se sienten auténticos para el público objetivo.

El aviso funciona mejor cuando se vuelve específico sobre la demografía, los puntos débiles y los contextos. “Actúa como un estudiante de último año de secundaria que solicita a la universidad” produce mejores ideas que “actuar como un adolescente”.

4. El mensaje mínimo de diseñador de prueba viable chatgpt

“Quiero probar esta idea de negocio: [describe concept] sin gastar más de [budget amount] o más de [time commitment]. Diseñe tres experimentos simples que podría ejecutar esta semana para validar la demanda de los clientes. Para cada prueba, explique lo que aprendería, cómo medir el éxito y qué resultados indicarían que debería avanzar “.

Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a adoptar la metodología Lean Startup sin perderse en la jerga comercial. El enfoque en “This Week” crea urgencia y evita la planificación interminable sin acción.

Un adolescente que desea probar un concepto de línea de ropa podría usar este indicador para diseñar experimentos de validación simples, como publicar maquetas de diseño en las redes sociales para evaluar el interés, crear un formulario de Google para recolectar pedidos anticipados y pedirles a los amigos que compartan el concepto con sus redes. Estas pruebas no cuestan nada más que proporcionar datos cruciales sobre la demanda y los precios.

5. El aviso de chatgpt del generador de claridad de tono

“Convierta esta idea de negocio en una clara explicación de 60 segundos: [describe your business]. La explicación debe incluir: el problema que resuelve, su solución, a quién ayuda, por qué lo elegirían sobre las alternativas y cómo se ve el éxito. Escríbelo en lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría “.

La comunicación clara separa a los empresarios exitosos de aquellos con buenas ideas pero una ejecución deficiente. Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a destilar conceptos complejos a explicaciones convincentes que pueden usar en todas partes, desde las publicaciones en las redes sociales hasta las conversaciones con posibles mentores.

El énfasis en el “lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría” es importante. Muchas plantillas de lanzamiento comercial suenan artificiales cuando se entregan jóvenes fundadores. La autenticidad es más importante que la jerga corporativa.

Más allá de las indicaciones de chatgpt: estrategia de implementación

La diferencia entre los adolescentes que usan estas indicaciones de manera efectiva y aquellos que no se reducen a seguir. ChatGPT proporciona dirección, pero la acción crea resultados.

Los jóvenes empresarios más exitosos con los que trabajo usan estas indicaciones como puntos de partida, no de punto final. Toman las sugerencias generadas por IA e inmediatamente las prueban en el mundo real. Llaman a clientes potenciales, crean prototipos simples e iteran en función de los comentarios reales.

Investigaciones recientes de Junior Achievement muestran que el 69% de los adolescentes tienen ideas de negocios, pero se sienten inciertos sobre el proceso de partida, con el miedo a que el fracaso sea la principal preocupación para el 67% de los posibles empresarios adolescentes. Estas indicaciones abordan esa incertidumbre al desactivar los conceptos abstractos en los próximos pasos concretos.

La imagen más grande

Los emprendedores adolescentes que utilizan herramientas de IA como ChatGPT representan un cambio en cómo está ocurriendo la educación empresarial. Según la investigación mundial de monitores empresariales, los jóvenes empresarios tienen 1,6 veces más probabilidades que los adultos de querer comenzar un negocio, y son particularmente activos en la tecnología, la alimentación y las bebidas, la moda y los sectores de entretenimiento. En lugar de esperar clases de emprendimiento formales o programas de MBA, estos jóvenes fundadores están accediendo a herramientas de pensamiento estratégico de inmediato.

Esta tendencia se alinea con cambios más amplios en la educación y la fuerza laboral. El Foro Económico Mundial identifica la creatividad, el pensamiento crítico y la resiliencia como las principales habilidades para 2025, la capacidad de las capacidades que el espíritu empresarial desarrolla naturalmente.

Programas como WIT brindan soporte estructurado para este viaje, pero las herramientas en sí mismas se están volviendo cada vez más accesibles. Un adolescente con acceso a Internet ahora puede acceder a recursos de planificación empresarial que anteriormente estaban disponibles solo para empresarios establecidos con presupuestos significativos.

La clave es usar estas herramientas cuidadosamente. ChatGPT puede acelerar el pensamiento y proporcionar marcos, pero no puede reemplazar el arduo trabajo de construir relaciones, crear productos y servir a los clientes. La mejor idea de negocio no es la más original, es la que resuelve un problema real para personas reales. Las herramientas de IA pueden ayudar a identificar esas oportunidades, pero solo la acción puede convertirlos en empresas que importan.

Noticias

Chatgpt vs. gemini: he probado ambos, y uno definitivamente es mejor

Published

8 meses agoon

5 junio, 2025

Precio

ChatGPT y Gemini tienen versiones gratuitas que limitan su acceso a características y modelos. Los planes premium para ambos también comienzan en alrededor de $ 20 por mes. Las características de chatbot, como investigaciones profundas, generación de imágenes y videos, búsqueda web y más, son similares en ChatGPT y Gemini. Sin embargo, los planes de Gemini pagados también incluyen el almacenamiento en la nube de Google Drive (a partir de 2TB) y un conjunto robusto de integraciones en las aplicaciones de Google Workspace.

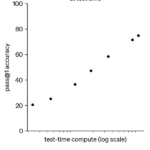

Los niveles de más alta gama de ChatGPT y Gemini desbloquean el aumento de los límites de uso y algunas características únicas, pero el costo mensual prohibitivo de estos planes (como $ 200 para Chatgpt Pro o $ 250 para Gemini Ai Ultra) los pone fuera del alcance de la mayoría de las personas. Las características específicas del plan Pro de ChatGPT, como el modo O1 Pro que aprovecha el poder de cálculo adicional para preguntas particularmente complicadas, no son especialmente relevantes para el consumidor promedio, por lo que no sentirá que se está perdiendo. Sin embargo, es probable que desee las características que son exclusivas del plan Ai Ultra de Gemini, como la generación de videos VEO 3.

Ganador: Géminis

Plataformas

Puede acceder a ChatGPT y Gemini en la web o a través de aplicaciones móviles (Android e iOS). ChatGPT también tiene aplicaciones de escritorio (macOS y Windows) y una extensión oficial para Google Chrome. Gemini no tiene aplicaciones de escritorio dedicadas o una extensión de Chrome, aunque se integra directamente con el navegador.

(Crédito: OpenAI/PCMAG)

Chatgpt está disponible en otros lugares, Como a través de Siri. Como se mencionó, puede acceder a Gemini en las aplicaciones de Google, como el calendario, Documento, ConducirGmail, Mapas, Mantener, FotosSábanas, y Música de YouTube. Tanto los modelos de Chatgpt como Gemini también aparecen en sitios como la perplejidad. Sin embargo, obtiene la mayor cantidad de funciones de estos chatbots en sus aplicaciones y portales web dedicados.

Las interfaces de ambos chatbots son en gran medida consistentes en todas las plataformas. Son fáciles de usar y no lo abruman con opciones y alternar. ChatGPT tiene algunas configuraciones más para jugar, como la capacidad de ajustar su personalidad, mientras que la profunda interfaz de investigación de Gemini hace un mejor uso de los bienes inmuebles de pantalla.

Ganador: empate

Modelos de IA

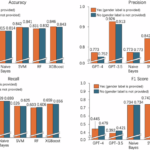

ChatGPT tiene dos series primarias de modelos, la serie 4 (su línea de conversación, insignia) y la Serie O (su compleja línea de razonamiento). Gemini ofrece de manera similar una serie Flash de uso general y una serie Pro para tareas más complicadas.

Los últimos modelos de Chatgpt son O3 y O4-Mini, y los últimos de Gemini son 2.5 Flash y 2.5 Pro. Fuera de la codificación o la resolución de una ecuación, pasará la mayor parte de su tiempo usando los modelos de la serie 4-Series y Flash. A continuación, puede ver cómo funcionan estos modelos en una variedad de tareas. Qué modelo es mejor depende realmente de lo que quieras hacer.

Ganador: empate

Búsqueda web

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden buscar información actualizada en la web con facilidad. Sin embargo, ChatGPT presenta mosaicos de artículos en la parte inferior de sus respuestas para una lectura adicional, tiene un excelente abastecimiento que facilita la vinculación de reclamos con evidencia, incluye imágenes en las respuestas cuando es relevante y, a menudo, proporciona más detalles en respuesta. Gemini no muestra nombres de fuente y títulos de artículos completos, e incluye mosaicos e imágenes de artículos solo cuando usa el modo AI de Google. El abastecimiento en este modo es aún menos robusto; Google relega las fuentes a los caretes que se pueden hacer clic que no resaltan las partes relevantes de su respuesta.

Como parte de sus experiencias de búsqueda en la web, ChatGPT y Gemini pueden ayudarlo a comprar. Si solicita consejos de compra, ambos presentan mosaicos haciendo clic en enlaces a los minoristas. Sin embargo, Gemini generalmente sugiere mejores productos y tiene una característica única en la que puede cargar una imagen tuya para probar digitalmente la ropa antes de comprar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Investigación profunda

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden generar informes que tienen docenas de páginas e incluyen más de 50 fuentes sobre cualquier tema. La mayor diferencia entre los dos se reduce al abastecimiento. Gemini a menudo cita más fuentes que CHATGPT, pero maneja el abastecimiento en informes de investigación profunda de la misma manera que lo hace en la búsqueda en modo AI, lo que significa caretas que se puede hacer clic sin destacados en el texto. Debido a que es más difícil conectar las afirmaciones en los informes de Géminis a fuentes reales, es más difícil creerles. El abastecimiento claro de ChatGPT con destacados en el texto es más fácil de confiar. Sin embargo, Gemini tiene algunas características de calidad de vida en ChatGPT, como la capacidad de exportar informes formateados correctamente a Google Docs con un solo clic. Su tono también es diferente. Los informes de ChatGPT se leen como publicaciones de foro elaboradas, mientras que los informes de Gemini se leen como documentos académicos.

Ganador: chatgpt

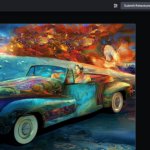

Generación de imágenes

La generación de imágenes de ChatGPT impresiona independientemente de lo que solicite, incluso las indicaciones complejas para paneles o diagramas cómicos. No es perfecto, pero los errores y la distorsión son mínimos. Gemini genera imágenes visualmente atractivas más rápido que ChatGPT, pero rutinariamente incluyen errores y distorsión notables. Con indicaciones complicadas, especialmente diagramas, Gemini produjo resultados sin sentido en las pruebas.

Arriba, puede ver cómo ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Géminis (segunda diapositiva) les fue con el siguiente mensaje: “Genere una imagen de un estudio de moda con una decoración simple y rústica que contrasta con el espacio más agradable. Incluya un sofá marrón y paredes de ladrillo”. La imagen de ChatGPT limita los problemas al detalle fino en las hojas de sus plantas y texto en su libro, mientras que la imagen de Gemini muestra problemas más notables en su tubo de cordón y lámpara.

Ganador: chatgpt

¡Obtenga nuestras mejores historias!

Toda la última tecnología, probada por nuestros expertos

Regístrese en el boletín de informes de laboratorio para recibir las últimas revisiones de productos de PCMAG, comprar asesoramiento e ideas.

Al hacer clic en Registrarme, confirma que tiene más de 16 años y acepta nuestros Términos de uso y Política de privacidad.

¡Gracias por registrarse!

Su suscripción ha sido confirmada. ¡Esté atento a su bandeja de entrada!

Generación de videos

La generación de videos de Gemini es la mejor de su clase, especialmente porque ChatGPT no puede igualar su capacidad para producir audio acompañante. Actualmente, Google bloquea el último modelo de generación de videos de Gemini, VEO 3, detrás del costoso plan AI Ultra, pero obtienes más videos realistas que con ChatGPT. Gemini también tiene otras características que ChatGPT no, como la herramienta Flow Filmmaker, que le permite extender los clips generados y el animador AI Whisk, que le permite animar imágenes fijas. Sin embargo, tenga en cuenta que incluso con VEO 3, aún necesita generar videos varias veces para obtener un gran resultado.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité a ChatGPT y Gemini a mostrarme un solucionador de cubos de Rubik Rubik que resuelva un cubo. La persona en el video de Géminis se ve muy bien, y el audio acompañante es competente. Al final, hay una buena atención al detalle con el marco que se desplaza, simulando la detención de una grabación de selfies. Mientras tanto, Chatgpt luchó con su cubo, distorsionándolo en gran medida.

Ganador: Géminis

Procesamiento de archivos

Comprender los archivos es una fortaleza de ChatGPT y Gemini. Ya sea que desee que respondan preguntas sobre un manual, editen un currículum o le informen algo sobre una imagen, ninguno decepciona. Sin embargo, ChatGPT tiene la ventaja sobre Gemini, ya que ofrece un reconocimiento de imagen ligeramente mejor y respuestas más detalladas cuando pregunta sobre los archivos cargados. Ambos chatbots todavía a veces inventan citas de documentos proporcionados o malinterpretan las imágenes, así que asegúrese de verificar sus resultados.

Ganador: chatgpt

Escritura creativa

Chatgpt y Gemini pueden generar poemas, obras, historias y más competentes. CHATGPT, sin embargo, se destaca entre los dos debido a cuán únicas son sus respuestas y qué tan bien responde a las indicaciones. Las respuestas de Gemini pueden sentirse repetitivas si no calibra cuidadosamente sus solicitudes, y no siempre sigue todas las instrucciones a la carta.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Gemini (segunda diapositiva) con lo siguiente: “Sin hacer referencia a nada en su memoria o respuestas anteriores, quiero que me escriba un poema de verso gratuito. Preste atención especial a la capitalización, enjambment, ruptura de línea y puntuación. Dado que es un verso libre, no quiero un medidor familiar o un esquema de retiro de la rima, pero quiero que tenga un estilo de coohes. ChatGPT logró entregar lo que pedí en el aviso, y eso era distinto de las generaciones anteriores. Gemini tuvo problemas para generar un poema que incorporó cualquier cosa más allá de las comas y los períodos, y su poema anterior se lee de manera muy similar a un poema que generó antes.

Recomendado por nuestros editores

Ganador: chatgpt

Razonamiento complejo

Los modelos de razonamiento complejos de Chatgpt y Gemini pueden manejar preguntas de informática, matemáticas y física con facilidad, así como mostrar de manera competente su trabajo. En las pruebas, ChatGPT dio respuestas correctas un poco más a menudo que Gemini, pero su rendimiento es bastante similar. Ambos chatbots pueden y le darán respuestas incorrectas, por lo que verificar su trabajo aún es vital si está haciendo algo importante o tratando de aprender un concepto.

Ganador: chatgpt

Integración

ChatGPT no tiene integraciones significativas, mientras que las integraciones de Gemini son una característica definitoria. Ya sea que desee obtener ayuda para editar un ensayo en Google Docs, comparta una pestaña Chrome para hacer una pregunta, pruebe una nueva lista de reproducción de música de YouTube personalizada para su gusto o desbloquee ideas personales en Gmail, Gemini puede hacer todo y mucho más. Es difícil subestimar cuán integrales y poderosas son realmente las integraciones de Géminis.

Ganador: Géminis

Asistentes de IA

ChatGPT tiene GPT personalizados, y Gemini tiene gemas. Ambos son asistentes de IA personalizables. Tampoco es una gran actualización sobre hablar directamente con los chatbots, pero los GPT personalizados de terceros agregan una nueva funcionalidad, como el fácil acceso a Canva para editar imágenes generadas. Mientras tanto, terceros no pueden crear gemas, y no puedes compartirlas. Puede permitir que los GPT personalizados accedan a la información externa o tomen acciones externas, pero las GEM no tienen una funcionalidad similar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Contexto Windows y límites de uso

La ventana de contexto de ChatGPT sube a 128,000 tokens en sus planes de nivel superior, y todos los planes tienen límites de uso dinámicos basados en la carga del servidor. Géminis, por otro lado, tiene una ventana de contexto de 1,000,000 token. Google no está demasiado claro en los límites de uso exactos para Gemini, pero también son dinámicos dependiendo de la carga del servidor. Anecdóticamente, no pude alcanzar los límites de uso usando los planes pagados de Chatgpt o Gemini, pero es mucho más fácil hacerlo con los planes gratuitos.

Ganador: Géminis

Privacidad

La privacidad en Chatgpt y Gemini es una bolsa mixta. Ambos recopilan cantidades significativas de datos, incluidos todos sus chats, y usan esos datos para capacitar a sus modelos de IA de forma predeterminada. Sin embargo, ambos le dan la opción de apagar el entrenamiento. Google al menos no recopila y usa datos de Gemini para fines de capacitación en aplicaciones de espacio de trabajo, como Gmail, de forma predeterminada. ChatGPT y Gemini también prometen no vender sus datos o usarlos para la orientación de anuncios, pero Google y OpenAI tienen historias sórdidas cuando se trata de hacks, filtraciones y diversos fechorías digitales, por lo que recomiendo no compartir nada demasiado sensible.

Ganador: empate

Related posts

Trending

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoRemove.bg: La Revolución en la Edición de Imágenes que Debes Conocer

-

Tutoriales2 años ago

Tutoriales2 años agoCómo Comenzar a Utilizar ChatGPT: Una Guía Completa para Principiantes

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoStartups de IA en EE.UU. que han recaudado más de $100M en 2024

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoDeepgram: Revolucionando el Reconocimiento de Voz con IA

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoCómo Empezar con Popai.pro: Tu Espacio Personal de IA – Guía Completa, Instalación, Versiones y Precios

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoPerplexity aplicado al Marketing Digital y Estrategias SEO

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial Aplicada de 4Geeks Academy 2024

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial de UC Berkeley estratégico para negocios