Noticias

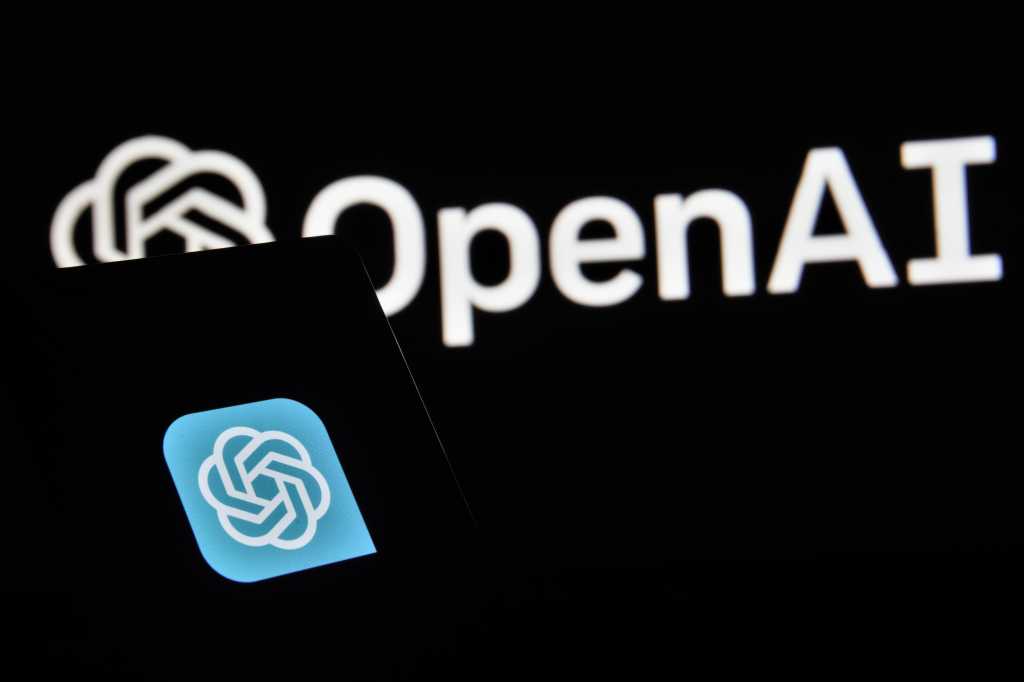

OpenAI Researcher Dan Roberts on What Physics Can Teach Us About AI

Contents

Dan Roberts: In the 40s, the physicists went to the Manhattan Project. Even if they were doing other things, that was, that was the place to be. And so now AI is the same thing and, you know, basically OpenAI is that place. So maybe, maybe we don’t need a public sector organized Manhattan Project, but it, you know, it can be OpenAI.

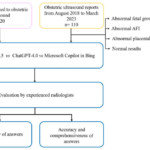

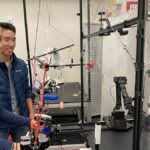

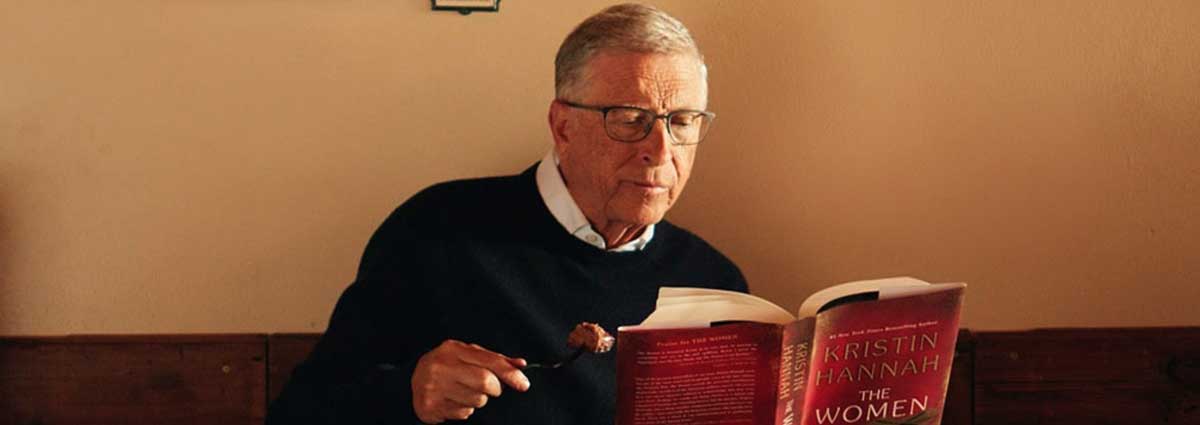

Sonya Huang: Joining us for this episode is Dan Roberts, a former Sequoia AI Fellow who recently joined OpenAI as a researcher. This episode was recorded on Dan’s second-to-last day at Sequoia, before he knew that he would go on to become a core contributor to o1, also known as Strawberry.

Dan is a quantum physicist who did undergraduate research on invisibility cloaks before getting a PhD at MIT and doing his postdoc at the legendary Princeton IAS. Dan has researched and written extensively about the intersection of physics and AI.

There are two main things we hope to learn from Dan in this episode. First, what can physics teach us about AI? What are the physical limits on an intelligence explosion and the limits of scaling laws, and how can we ever hope to understand neural nets? And second, what can AI teach us about physics and math and how the world works?

Thank you so much for joining us today, Dan.

The path to physics

Dan Roberts: Thanks. Delighted to be here on my, probably, second-to-last day at Sequoia. Depending on when this airs and how you’re going to talk about it.

Pat Grady: You will always be part of the Sequoia family, Dan.

Dan Roberts: Thanks, I appreciate it.

Sonya Huang: Maybe just to get started tell us a little bit about “Who is Dan?” You have a fascinating backstory. I think you worked on invisibility cloaks back in college. Like, what led you to become a theoretical physicist in the first place?

Dan Roberts: Yeah, I think–and this is, you know, my stock answer at this point, but I think it’s true–I was just an annoying three year old who never grew up. I asked “why” all the time. Curious. How does everything work? I have a 19-month at home right now, and I can see the way he followed the washing machine repairman around and had to look inside the washing machine. So like, I think I just kept that going. And when you’re more quantitatively oriented than not, rather than going to philosophy I think you sort of veer into physics. And that was sort of what interested me. How does the world work? What is all this other stuff that’s out there?

The question that you didn’t ask, but maybe I’ll just answer it ahead of time–the sort of inward facing stuff felt less quantitative and more in the realm of the humanities. Like, so “What is all this stuff?” That’s pretty physics-y. “What am I? Who am I? What does it mean to be me?” That felt not very science-y at all. But with AI it sort of seems like we can think about both “What does it mean to be intelligent,” and also “What is all this other stuff?” in some of the same frameworks. And so that’s been very exciting for me.

Sonya Huang: So we should be trying to recruit your 19-month-old right now is what you’re saying?

Dan Roberts: Oh yeah. Absolutely. He grew out of one of his Sequoia onesies, but he fits into a Sequoia toddler t-shirt now. And so he definitely is ready to be a future founder.

Sonya Huang: I guess, at what point did you know that you wanted to think about AI? At what point did that switch start to flip?

Dan Roberts: Yeah. So, I think like many people, when I discovered computers, I wanted to understand how they worked and how to program them. In undergrad, I took an AI class and it was very much good old fashioned AI. A lot of the ideas in that class actually are coming back to be relevant, but at the time it was, it seemed not very practical. It was a lot of, you know, “If this happens, do that.” And there was also some game-playing there. That was sort of interesting. It was very algorithmic, but it didn’t seem related to what it means to be intelligent.

What does it mean to be intelligent?

Pat Grady: Can we just pick up on that real quick? Like, what do you think it means to be intelligent?

Dan Roberts: That’s a great question.

Pat Grady: I can see wheels turning.

Dan Roberts: Yeah. Well, this is one of those questions where I don’t have a stock answer, but I think it’s important to not say nonsense. One of the things that’s exciting to me about AI is the ability to have systems that do what humans do, and to be able to understand them from “What are the lines of Python that cause that system to do something?” to, you know, to trace that through and understand what are the outputs, and you know, how the system can like, see and classify what it means. You know, “What is a cat? What is not a cat?” Or can write poetry and, you know, it’s just a few lines of code. Whereas, if you’re trying to study humans and ask, “What does it mean for humans to be intelligent?” you have to go from biology, through neuroscience, through psychology, up to other higher level versions of ways of approaching this question.

And so, I think maybe a nice answer for intelligence, at least the things that are interesting to me, is “The things that humans do.” And now, if you pull back the answer that I just said a second ago, that’s how I connect it to AI. AI is taking pieces of what humans do, and we’re understanding, at least an example that’s kind of simple and easy to study, that we might use to understand better what what it is that humans do.

The path to AI

Sonya Huang: So Dan, you mentioned when you were, you know, studying AI in college, there was a lot of what sounds like kind of hard-coded logic and brute force type approaches. Was there a moment that kind of clicked for you, of like, “Oh, okay. This is different”? Was there a key result or a moment where it was like, “Okay, we’re going bigger places than kind of the ‘if this, then that’ logic of the past”?

Dan Roberts: Yeah, actually it didn’t click. I sort of wrote it off. And it would be great if there was a separation between like ten years between then and the next thing that I’m going to say, but actually the writing-off maybe lasted a year or two, because then I went to the UK for the first part of grad school. I spent a very long time in grad school and I discovered machine learning and a more statistical approach to artificial intelligence, where you have a bunch of examples of large amounts of data. Or at the time, maybe we wouldn’t have said large amounts of data, but we would have said, you have data examples of a task that you want to perform. And there’s different ways that machine learning works, but you write down a very flexible algorithm that can adapt to these examples and start to perform in a way similar to the examples that you have.

And that approach borrows a lot from physics. It also, at the time, I started… So graduated college in 2009. Discovered machine learning in 2010, 2011. 2012 is the big year for deep learning. And so, you know, there’s not a big separation here between write-off and rediscovery. But I think–and machine learning clearly existed in 2009, it just wasn’t related to the class that I took–but this approach made a lot of sense to me. And it started to have, you know, I got lucky, and then it started to have real progress and seemed to fit in a framework that I understood scientifically. And I got very excited about it.

Sonya Huang: Why do you think there are so many people who come from a similar background or similar path to you? Like, a lot of ex-physicists working on AI. Like, is that a coincidence? Is that herd behavior, or do you think there’s something that makes physicists particularly well suited to understanding AI?

Dan Roberts: I think the answer is yes to all the ways you…

Sonya Huang: All the above.

Dan Roberts: You know, physicists infiltrate lots of different subjects, and we get parodied about the way that we go about trying to use our hammers to tackle these things that may or may not be nails. Throughout history, there are a lot of times that physicists have contributed to things that look like machine learning. I think in the near term, the path that physicists used to take when they didn’t remain in academia often was going into quantitative finance, then data science. And I think machine learning, and its realization in industry, was exciting because, again, it’s something that feels a lot like actual physics and is working towards a problem that’s very interesting and exciting for a lot of people.

You know, you’re doing this podcast because you’re excited about AI. Everyone’s excited about AI. And in many ways it’s a research problem that feels a lot like the physics that people were doing. But I think the methods of physics actually are different from the methods of traditional computer science and very well suited for studying large scale machine learning that we use to work on AI.

Traditionally physics involves a lot of interplay between theory and experiment. You come up with some sort of model that you have some sort of theoretical intuition about. Then you go and do a bunch of experiments and you validate that model or not. And then there’s this tight feedback loop between collecting data, coming up with theories, coming up with toy models. Understanding moves forward by that. And, you know, we get these really nice explanatory theories. And I think the way that big deep learning systems work, you have this tight feedback loop where you can do a number of experiments. The sort of math that we use is very well suited to the math that a lot of physicists are familiar with. And so I think it’s very natural for a lot of physicists to work on this. And those tools, a number of them differ from the traditional, at least theoretical, computer science and theoretical machine learning tools for studying the theoretical side of machine learning, and maybe also differentiation between just being an awesome engineer and also being a scientist. And there’s tools from doing science that are helpful in studying these systems.

Pat Grady: Dan, you wrote this, what I thought was a beautiful article, Black Holes and the Intelligence Explosion, and in there you talk about this concept of, sort of the microscopic point of view, and then the system level point of view and how physics really equips people to think about the system level point of view, and that has a sort of complimentary benefit to understanding these systems. Can you just take a minute and kind of explain sort of microscopic versus system level, and how the physics influence helps to understand the system level?

Dan Roberts: Sure. So, let me start with an analogy that I think is, like, very, you know, goes even further than an analogy. But going back, what year is it? Maybe like 200 years or so around the time of the Industrial Revolution, there was steam engines and steam power and a lot of technology that resulted from this and ultimately powered industrialization. And in the beginning, there was a lot of engineering of these steam engines, you know, and there was this high level theory of how this work called thermodynamics, where, you know, and I imagine everyone’s seen this in high school, perhaps where, you know, there’s the Ideal Gas Law that tells you that there’s some relationship between pressure and volume and temperature. And, you know, these are very macro level things. Like you can buy a thermometer. You can also measure the volume of your room and you can buy a barometer as well. Maybe people don’t or look up on the weather report. But, you know, these are like measurements that we use and we talk about. But then underlying this, and it took us a bit later to validate this and understand it, there’s the notion of atoms and molecules, the air molecules bouncing around. And somehow we now understand that those air molecules give rise to things like temperature and pressure and volume. I guess it is easier to understand that the gases, the molecules, are confined to a room.

But there’s a precise way in which you can start with a statistical understanding of those molecules and derive thermodynamics, like, derive the Ideal Gas Law from it. And you can go further than that to derive that it’s ideal because it’s wrong. It’s just a toy model. But you can, there are corrections to it, and you can sort of understand, you know, from the microscopic perspective, which is the molecules, which we don’t really interact with. You know, we don’t see them, we don’t interact with them on a day-to-day basis, but their statistical aggregate properties give rise to, sort of, this behavior that we do see at the macro scale.

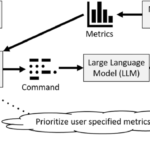

And part of, to get to your question, you know, I think there’s a similar thing going on with deep learning systems. And I wrote a book with Sho Yaida and Boris Hanin on how to apply these sorts of ideas to deep learning, and, at least in an initial framework that allows you to start doing this in an initial way. And to answer your question, the sort of micro perspective is you have neurons and weights and biases, and we can talk about in detail how that works, but when people think of the architecture, there’s some very specific, some people say circuits, there’s specific ways in which these things, you know, there’s an input signal which might be an image or text, and then there’s many parameters. And, you know, it’s very simple to write down. It’s not that many lines of code even taking into account the machine learning libraries, but it’s, you know, it’s like a very simple set of equations. But there’s a lot of weights. There’s a lot of numbers that you have to know in order to get it to do something. And that’s sort of the micro… that’s like the molecules perspective.

And then there’s like the macro perspective, which is, well, what did it do? Did it produce a poem? Did it solve a math problem? How does, how do we go from that, those weights and biases to, to that macro perspective? And so for statistical physics to thermodynamics, we understand that completely. And you can imagine trying to do the same sort of thing, literally applying the same sorts of methods to understand how does the underlying micro statistical behavior of these models lead to the sort of macro or, as you said, system level perspective?

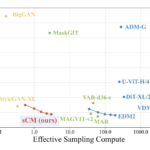

Sonya Huang: Dan, maybe speaking of scaling laws, and I think you were at our event, AI Ascent, Andre Karpathy mentioned that current AI systems are like 5 or 6 orders of magnitude off in efficiency compared to biological neural nets. How do you think about that? Do you think scaling laws get us there? Just a combination of scaling laws plus hardware getting more efficient or, like, do you think that there’s kind of big step function leaps that need to come in research?

Dan Roberts: There’s maybe two things that could be meant here. One is that the way humans seem to work at a similar scale to AI systems is much more efficient. You know, we don’t need to see trillions of tokens before we speak. You know, my toddler is already starting to speak in sentences. And he’s been exposed to far less tokens than a typical large language model. And so there’s some sort of disconnect between human efficiency at learning and what large language models do. Of course, they’re very different systems. They’re designed, you know, the way in which they learn is right now very different. And so in some sense that’s to be expected. So, there’s this gap here that you could imagine bridging.

There’s another thing that I think is not what you meant, but I think is sort of the thing to answer about with respect to scaling laws, which is, and I talked about this a bit in the article, but lots of people seem to talk about this, which is “What is the final GPT?” You know, there’s GPT-4 right now, and it could be other companies as well, but since I’m going to join OpenAI let me represent my new company, right? So is it going to be six? Is it going to be seven? At some point, assuming we have to scale things up, there are things that are going to break. Whether they’re economic, we’re going to run out of, you know, we’re going to try to train a model that’s larger than the world’s GDP or GWP, however, the D works for the world. Or we’re going to run out of, you know, we’re not going to be able to produce enough GPUs. Or we’re not going to be able to put, you know, it’s going to cover the surface of the Earth. You know, a lot of these things are going to break down at some point. And so probably the economic one happens first. So how many, you know, how many more iterations do we get before we run out of actually being able to scale practically? And where does that get us? And then, I think, to tie those two perspectives together, there’s scaling on its own. And of course, it’s impossible to disentangle this because people are making things more efficient.

But you know, there’s like, you could imagine there’s the, take literally what GPT-2 was, which was the initial big model, and keep scaling it up. Is that going to get us to some, you know, super different, exciting, economically powerful, or however you want to define what the end state of AI research and AI startups and AI in industry is? Or do we need lots of new exciting ideas? And, and again, of course, you can’t really disentangle these, but I think the general scaling hypothesis is that it’s just the scaling and it’s not the ideas that matter. Whereas, the “How do we get to be efficient like humans?” I think requires, like, non-trivial ideas. And to answer your question, the reason I’m excited about joining OpenAI is that I think there is high leverage to be had in the ideas, you know, in going beyond scaling, and that we will need that in order to get to the next steps. I have no idea what I’ll be working on, but when this airs I guess I will know what I’m working on, but you know that that’s what’s really exciting to me.

The pendulum between scale and ideas

Pat Grady: Dan, is there almost like a pendulum that swings back and forth between scale and ideas in terms of how people apply their efforts in the world of AI? Like, transformers came out. Great idea. Since then, we’ve largely been in this race to scale. It feels like things are starting to asymptote for a bunch of practical reasons that you mentioned. Is the pendulum swinging back toward ideas as the currency? You know, it’s less now about who can, you know, have the biggest GPU cluster and more about finding new architectural breakthroughs, whether that’s, you know, reasoning or something else?

Dan Roberts: Yeah. That’s a really great question. I think there’s this article by Richard Sutton called The Bitter Lesson, not the bitter pill, and it basically gives the argument that ideas aren’t important, that scale is what you need, and that all the ideas are always trumped by scaling, by scaling things up. It says a bunch of things, but maybe that’s a high level takeaway. And, you know, there’s a sense of this where there are a lot of interesting ideas that came out in the 80s and 90s that people didn’t really have scale to explore. And then, I remember when, after AlphaGo and DeepMind was writing a lot of papers, people were rediscovering those papers and re-implementing them in deep learning systems. But this was sort of still before people realized, “No, the thing that you need to do is scale up.” And even now, with transformers, people are exploring other architectures or even simpler architectures that we knew before that seem to be able to, you know, there’s a notion, you know, maybe scaling laws don’t come from as long as the architecture isn’t sick in some way.

They come from sort of the underlying data process and having large amounts of data rather than from having a special idea. I think the real answer is that there’s a balance between the two. That scale is hugely important, and maybe it was just not understood how important. And we also didn’t have the resources to to scale things up at various times, you know, the things that have to go into producing these GPU clusters that are producing these models are, you know, you guys know this as well, like there’s a lot of parts along the supply chain, or along the product chain, whatever you actually call it, in order to make those things happen and to deploy them. And even, you know, the way GPUs were originally, they’ve now co-evolved to be well suited for these models. And the reason, in some sense, you can think of transformers was a good idea was because it was designed to be well-suited to train on the systems that we had at the time. And so sure, these other architectures could do it at an ideal scientific level, but at a practical level, it was important to to get something that was that that was able to to reach that scale.

So I think, you know, if you brought in ideas to be that sort of thing that’s married with scale in some way, then I still think ultimately, like, you know, someone came up with the idea of deep learning. That was an important idea. You know, there’s Pitts and McCulloch came up with the original idea for the neuron. Rosenblatt came up with the original perceptron. And there’s like a lot of people, from going back like 80 or so years, of people just making important discoveries that were ideas that contribute. So, I think it’s both. But it’s easy to see how, you know, if you’re bottlenecked, people think about ideas. And then if you unlock a new capacity of scale somehow, then you just see a huge set of results. And it seems like scale is super important. And I really think it’s more of a synergy between the two.

The Manhattan Project of AI

Sonya Huang: Maybe on the topic of the race to scale, Dan, you mentioned kind of just the economic constraints and realities, which I guess are more, like, practically a ceiling in the private sector. You also mentioned the Manhattan Project earlier in terms of things that physicists have been involved with. Like, do you think we need a Manhattan Project style thing for AI? Like at the nation state or at the international level?

Dan Roberts: Well, one thing I can say is that part of the process that led me to OpenAI is I was talking with your partner, Shaun Maguire, who brought me to Sequoia in the first place, and trying to figure out is there a startup that makes sense for me to work on that has the right mix of, sort of, scientific questions, research questions, and also as a business? And I think it was Shaun that said–and I don’t mean the analogy in terms of the impact of, you know, in terms of like negative impact of what you might think of the Manhattan Project, but just in terms of the scale and the organization–he said, “You know, in the 40s, the physicists’ physicist went to the Manhattan Project. Even if they were doing other things, that was the place to be.” And so now AI is the same thing, and basically said OpenAI is that place. So maybe, maybe we don’t need a public sector organized Manhattan Project, but it, you know, it can be OpenAI.

Sonya Huang: OpenAI as the Manhattan Project. I love that.

Dan Roberts: Well, maybe that’s not a direct quote that we want to be taken out of context, but I think in terms of…

Sonya Huang: The metaphorical Manhattan Project.

Dan Roberts:Yeah. In terms of scale and ambition. I mean, I think a lot of physicists would love to work at OpenAI for a lot of the same reasons that they probably were excited to… Well, okay, there’s a number of different reasons. Maybe we just have to leave it as a nuanced thing rather than making broad claims.

AI’s black box

Sonya Huang: Can we talk a little bit about this… Like, can we ever understand AI, especially as we go to these deep neural nets, or do you think it’s a hopeless black box, so to speak?

Dan Roberts: Yeah, I think within the… This is my answer to the “What are you a contrarian about?” Although maybe, you know, on the internet everyone takes every side of every position, so it’s hard to say you have a contrarian position. But I think within AI communities, you know, I think my contrarian position is that we can really understand these systems. And in, you know, physics systems are extremely complicated, and we have made a huge amount of progress in understanding them. I think these systems sit in the same framework. And, you know, another principle that Sho and I talk about in our book, and that’s a principle of physics, is that there’s this often extreme simplicity at very large scales, basically due to the statistical averaging, or more technically, the central limit theorem. Things can simplify–and I’m not saying this is what happens exactly in large language models, Of course not–but I do think that we can apply sort of the methods that we have and also, you know, maybe hopefully have AI that can help us do this in the future. And by AI, I mean tools. Not like individual intelligences just going running on their own and solving these problems. But I guess I feel at the extreme end that this is not going to be an art, that the science will will catch up and that it will will be able to make extreme leaps in really understanding how these systems work and behave.

What can AI teach us about physics?

Pat Grady: So, Dan, we’ve talked a bunch about what physics can teach us about AI. Can we talk a bit about what AI can teach us about physics? Are you optimistic about domains like physics and math and how these emerging models can, you know, probe further into those domains?

Dan Roberts: Yes, I’m definitely optimistic. I guess my perspective is that math will be easier than physics, which maybe betrays the fact that I’m a physicist, not a mathematician. And I’ll say–I can give explain why I think that in a second–but, you know, I still have a lot of friends that work in physics and they, you know, there’s like a growing sense and maybe even approaching a dread, that maybe this is actually the answer to “Why do physicists work on AI?” Because, you know, if what you care about is the answer to your physics question and you want to make it happen as soon as possible, what is the highest leverage thing you can do? Maybe it’s not work on the physics question you care about, but it’s work on AI to make the, you know, because you think that the AI might end up solving those questions very rapidly anyway. And I don’t know the extent that anyone really takes it seriously, but I think within the theoretical physics community that I come from, that this is sort of a thing that somewhat gets thrown around and discussed.

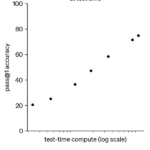

I think maybe to give a more object-level answer, I think what’s exciting about math–and maybe when you have Noam Brown on, if you have him on, he’ll talk about this, but this is something that that he’s talked about for a while before he joined OpenAI–I think the that we have, you know, we made a lot of progress in terms of solving games by doing more than just looking up what is the strategy that we should use to play the games, but also being able to simulate forward and, you know, the way that if I’m in a very hard position in a particular game, rather than just playing with intuition, I might sit and think about what I should do. Yeah, sometimes this goes under the name inference-time compute rather than raining-time compute or pre-training. And you know, there’s a sense in which what it means to do reasoning is very related to this ability to sit and think. So we know how to do it for games because there’s a very clear winning and loss signal. So you can simulate ahead and sort of figure out what it means to do good or not. And I think math, in some parts of math–again, I’m not a mathematician and well, you know, I’m always scared about talking about math publicly and saying something wrong that will upset mathematicians–but it seems like certain types of math problems are not as constrained as games, but are still constrained enough where there’s a notion of like finding a proof, right? You know, there’s definite problems in terms of search, in terms of how do you figure out what is the next, you know, move in the proof, but the fact that we might call it a move suggests that there’s things in math that feel a lot like games. And so we might think the fact that we can do well at games maybe means that we can do well at certain types of mathematical discovery.

Can AI help solve physics’ biggest problems?

Pat Grady: Well, I was going to say since you mentioned Noam, he likes to use the example with test-time compute of whether it could help to prove the Riemann hypothesis. Is there a similar problem or hypothesis in the world of physics that you are optimistic AI can help to solve sometime in our lifetimes?

Dan Roberts: Yeah. So, I mean, there’s a Millennium Problem relating to physics–and if I try to remember exactly what it is I’m sure I will butcher it and then no one will believe that I’m actually a physicist–but it’s related to the, you know, it’s a mathematical physics question related to the Yang-Mills mass gap. But I think, what I wanted to say is that I think some of the flavor of what physicists care about and doing physics feels a little different. This is where I might get in trouble. It feels a little different than some of, like, the mathematical proof type things. Physicists are known to be more informal and, you know, hand-wavy. But also, on the other hand, connected to, in some sense, connected to the interplay between experiment and the sort of models that physicists study is maybe what saves them is that, you know, they have things that are informal and hand-wavy, but very explanatory. And then the mathematicians, it’s like we were saying earlier, the engineers discovered all the exciting industrial machines, and the physicists maybe cleaned up a bunch of the theory about how that works. And then the mathematicians come later and clean up, like, formalize everything and clean it up even more. And so there’s a mathematician or mathematical physicist that cleans up a lot of, you know, make proper and try and, you know, understand in formal ways some of the stuff that physicists do.

But rather than talking about–I mean, I think the key point there is that the sort of questions that are interesting to physicists maybe don’t look like proofs, and maybe it’s not about how do we, given a particular model, how do we actually solve it? Like once things are set up correctly, like it’s often, you know, senior or you know, people that are trained in the field are able to sort of figure out how to analyze those systems. It’s more the other stuff. Like, what is the right model to study? Does it capture the right sort of problems? Does this relate to the thing that you care about? What are the insights you can draw from it? And so for AI to help there, I think it would look different than the way we’re sort of trying to build AI systems for math. So rather than here’s, you know, here’s the word problem going, you know, solve this high school level problem or, you know, prove the Riemann hypothesis.

It’s like, you know, the questions in physics are like, “What is quantum gravity? What happens when something goes into a black hole?” And that’s not like, you know, start generating tokens on that. What does that even look like? And you know, if you go to a physics department, you know, people hang out at the blackboard. They chat about things. Like, maybe they sketch mathematical things, but you know, there’s a lot of other things that go into this. And so maybe the sort of data that you need to collect looks more like that. Or maybe it looks like the random emails and conversations on Slack and the scratch work. And so, I mean, there are definitely tools that we can use, like “Help me understand this new paper so I don’t have to spend two weeks trying to study it and understand it.” You know, maybe let me ask questions about it. I think there are problems with the way that’s currently implemented.

But, you know, I think there are a lot of tools that will help accelerate physicists just like Mathematica, which is a software package that does integrals, and it does a lot more than that. Sorry, Stephen Wolfram. But I use it to do integrals and, you know, sometimes it doesn’t know integrals and you can look them up in like these integral tables. Anyway. You know, I think, you know, and this applies to other branches of science too. Like, I think the ways in which the questions are asked and what it means to do science in different fields, maybe can look further and further from gains, let’s just say. And so to the extent that that’s true, I think we’ll need to. And not even clear that we’ll need lots of ideas or I mean, we we will need lots of ideas, but it’s more just like, we’ll have to, I think, we’ll just have to approach them all differently. And maybe not, like maybe eventually we’ll have a universal thing that knows how to do all of it. But initially, like at least to me, a lot of these things feel a little different from each other.

Sonya Huang: You’ll have a front row seat to it, in part because you’re also on the prize committee for the AI Math Olympiad, which is something I’m personally super interested in.

Maybe to your last point on, kind of like, maybe eventually this stuff generalizes. Like, why do you think people are so focused on solving the hardest problems today, like physics, math? Those were the subjects that everyone was terrified of in school, right? Where it feels like there’s a lot more other domains that are also unsolved for now. Like do you think, do you think going for the hardest domains first kind of lets you get towards a generalized intelligence? Like how does solving these different domains kind of fit together in the grander puzzle?

Dan Roberts: Yeah. The first thing that comes to mind when you said that is to just push back and say, “Well, it’s not hard. These are the easy domains.” I mean, I’m bad at biology. It doesn’t make any sense to me at all. My girlfriend actually is in bioengineering and is in biotech. And so, like, what she does just makes no sense to me. I can’t understand any of it, where physics makes complete sense to me. I think maybe a better answer or a less glib answer is that, like I was trying to say about math, there are constraints. And, you know, in particular with math, a lot of it is unembodied. You don’t have to go and do experiments in the real world. You know, they’re sort of self-sufficient and that’s close to, like, what generating text, like the way language models work, or even the way some reinforcement learning systems work for games. And so, I think the further that you go from that, the messier things become, the harder it probably is, and also the harder it is to get the right kind of data to train these systems.

If you want to build an AI–and people are trying to do this, but it seems difficult–if you want to build an AI system that solves biology, I guess you need to also make sure robotics works, you know, so that it can do those sorts of experiments and like it has to understand that sort of data. Or maybe it has humans do it. But, you know, there’s a lot, you know, for a self-sustaining AI biologist, it seems like there’s a lot of things that are going to go into it. I mean, on the way, we’ll have things like AlphaFold 3, which just came out and which I didn’t get a chance to read the details of, but, you know, I saw that they’re trying to use it for drug discovery. And so, you know, I think each of these fields will have things developed along the way. But I think the less constraints there are and the sort of messier and more embodied it is, the harder it will be to accomplish.

Sonya Huang: No, that makes sense. So, like hard for a human is not the same thing–doesn’t correlate to hard for machine.

Dan Roberts: Yeah. Plus, also maybe humans disagree about what’s hard or not.

Sonya Huang: Some of us think more like machines, I guess. And then I guess the second question was like, do you think it all coalesces into, like, one big model that understands everything? Because right now it seems like there’s a lot of domain-specific problem solving that’s happening.

Dan Roberts: Yeah. I mean, the way things are going, it seems like the answers should be yes. It’s really dangerous to speculate in this field because everything you say is wrong. Usually much sooner than later.

Sonya Huang: Good thing we’re on record. We’ll hold you to it.

Dan Roberts: Yeah, exactly. But also, like, what does it mean to be different? You know, like, there’s a trivial way to make both things–make the question meaningless–by, like you say, the model is the union of all those other models. But there’s also a sense in which mixture of experts was originally meant to be that, it’s not that in practice at all. But, you know, there is a sliding scale here. But, you know, it does seem like people, at least the big labs, are going for the one big model and have a belief that that’s, you know, well… I don’t know, but maybe I will in the future, understand what the philosophy is there.

Lightning round

Pat Grady: Dan, we have a handful of more general questions to kind of close things out here. So I’ll start with the high level one. If we think kind of short-term, medium-term, long-term and call it, you know, five months, five years, five decades, what are you most excited or optimistic about in the world of AI?

Dan Roberts: Five years ago was after the transformer model came out, but it was around maybe when GPT-2 came out. So it seems like, you know, for the last five years we’ve been doing scaling. I imagine within the next five years, we’ll see that scaling will terminate. And maybe it will terminate in, you know, a utopia of some kind, you know, that people are excited about where we’re all post-economic and so forth, and we’ll have to shut down all your funds and, you know, return monopoly money because money won’t matter. Or we’ll see that we need lots of ideas. Maybe there will be another AI winter.

I imagine that–and again, scary to really speculate–but I imagine, like something will be something will be interestingly different within five years about AI. And it might just be that AI is over and we’re on to the, you know, we’re on to the next exciting investment opportunity. And, you know, everyone else will shift elsewhere. And you know, I’m not saying that. That’s not what’s motivating me about AI, but, you know. So maybe five years is enough time to see that. And I think in, in one year, I mean, or there’s a five. I messed this up. Whatever. Maybe it was five months, I don’t remember. I’m sorry.

Pat Grady: It’s five months. It’s okay, it’s okay. These are approximations. I know you said physicists are very hand-wavy. Venture capitalists are very hand-wavy. These are approximations.

Dan Roberts: In physics there’s–I like to joke that there’s like three numbers. There’s zero, one and infinity. And, you know, those are the only numbers that matter. You know, things are either arbitrarily small, arbitrarily large, or about order one.

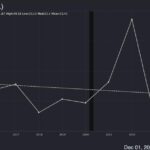

So. Okay. Good. Thanks for reminding me. But yeah, for five months, I mean, I’m excited to well, to learn what’s exciting at the forefront of a huge research lab like OpenAI. And I think one thing that will be interesting will be the delta between the next generation of models, right? Because there’s ways in which things are scaling up in terms of, it’s not really public, I guess, aside from Meta, but in terms of size of data, size of models. And we see scaling laws that relate to, you know, something like the loss and, you know, it’s hard to translate that into actual capabilities. And so what will it feel like to talk to the next generation model? What will it look like? Will it have a huge economic impact or not? And I think I, you know, in terms of estimating velocity, right, you need a few points. You can’t just have one point. And we sort of have, you know, we’re starting to have that with GPT-3 to GPT-4. .But, you know, I feel like with the next delta, we’ll get to really see what the velocity looks like and what it feels like going from model to model to model. And maybe I’ll be able to make a better prediction in five months from now, but then I guess I probably won’t be able to tell it to you guys.

Sonya Huang: Thanks, Dan. One thing that stood out to me is just like your writing is so accessible and light and funny, and that’s not what I’m used to when I read super technical stuff. Like, do you think all technical writing should be informal and funny? Like, is that deliberate?

Dan Roberts: It’s definitely deliberate. It goes into, I think in some sense it’s inherited. I mean, I definitely am a not serious person, but I also think it’s an inherited, sort of, from the style of the field that I came from. But I’ll tell you a story. I was at lunch. I was a postdoc at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and I was having lunch and joking around with this professor, Nati Seiberg, who’s a professor at the institute. And then we got into, I think we were talking about someone, someone asked a question about, like, “What is a good title?” And I was like, “Oh, the title has to be a joke.” And he was on board with that. And then I was explaining that for me, the reason to write a paper is for the jokes. Like you have a bunch of jokes in mind, and then you want people to read those jokes. And so you have to package it into the science product, and people want to read the science product, and they’re forced to suffer through the jokes. And Nati, who is this Israeli professor, he was like, “I don’t get it. Why? Why can’t you just do the science? Why do you need the, like… the jokes are great too, but like, you should write for the science, not for the jokes.”

And I was adamant that I write for the jokes. But I think it’s, I think it’s what you said that at some point, you know, you learn about the scientific method and, you know, the, the formal ways of doing things, and you learn all these rules and then you grow up a bit. Or maybe, I had a roommate who was a linguist, he’s now a professor of linguistics at UT Austin, and like, he emphasized that you can–he would tell me which rules that I could break or what, like where the rules come from and why they’re important or not. And you sort of realize that you can break these rules. And, like, the ultimate goal should be, is the reader going to read it and understand it and enjoy it. So you don’t want to do things that compromise their ability to read and understand. But you don’t want to obscure things. You want to make it, you know, if it’s more enjoyable, people are more likely to read it and take the point. It’s also more fun if you’re writing it. So I think that’s where that comes from.

Sonya Huang: Dan, thank you so much for joining us today. We learned a lot. We enjoyed your jokes and I hope you have. I hope you have a wonderful second-to-last day at Sequoia. Thank you for spending part of it with us. We really appreciate it.

Dan Roberts: Thanks. I was absolutely delighted to be here chatting with you guys. This was wonderful.

Noticias

Revivir el compromiso en el aula de español: un desafío musical con chatgpt – enfoque de la facultad

Noticias

5 indicaciones de chatgpt que pueden ayudar a los adolescentes a lanzar una startup

Teen emprendedor que usa chatgpt para ayudarlo con su negocio

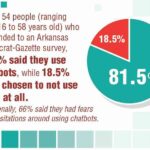

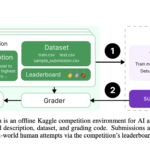

El emprendimiento adolescente sigue en aumento. Según Junior Achievement Research, el 66% de los adolescentes estadounidenses de entre 13 y 17 años dicen que es probable que considere comenzar un negocio como adultos, con el monitor de emprendimiento global 2023-2024 que encuentra que el 24% de los jóvenes de 18 a 24 años son actualmente empresarios. Estos jóvenes fundadores no son solo soñando, están construyendo empresas reales que generan ingresos y crean un impacto social, y están utilizando las indicaciones de ChatGPT para ayudarlos.

En Wit (lo que sea necesario), la organización que fundó en 2009, hemos trabajado con más de 10,000 jóvenes empresarios. Durante el año pasado, he observado un cambio en cómo los adolescentes abordan la planificación comercial. Con nuestra orientación, están utilizando herramientas de IA como ChatGPT, no como atajos, sino como socios de pensamiento estratégico para aclarar ideas, probar conceptos y acelerar la ejecución.

Los emprendedores adolescentes más exitosos han descubierto indicaciones específicas que los ayudan a pasar de una idea a otra. Estas no son sesiones genéricas de lluvia de ideas: están utilizando preguntas específicas que abordan los desafíos únicos que enfrentan los jóvenes fundadores: recursos limitados, compromisos escolares y la necesidad de demostrar sus conceptos rápidamente.

Aquí hay cinco indicaciones de ChatGPT que ayudan constantemente a los emprendedores adolescentes a construir negocios que importan.

1. El problema del primer descubrimiento chatgpt aviso

“Me doy cuenta de que [specific group of people]

luchar contra [specific problem I’ve observed]. Ayúdame a entender mejor este problema explicando: 1) por qué existe este problema, 2) qué soluciones existen actualmente y por qué son insuficientes, 3) cuánto las personas podrían pagar para resolver esto, y 4) tres formas específicas en que podría probar si este es un problema real que vale la pena resolver “.

Un adolescente podría usar este aviso después de notar que los estudiantes en la escuela luchan por pagar el almuerzo. En lugar de asumir que entienden el alcance completo, podrían pedirle a ChatGPT que investigue la deuda del almuerzo escolar como un problema sistémico. Esta investigación puede llevarlos a crear un negocio basado en productos donde los ingresos ayuden a pagar la deuda del almuerzo, lo que combina ganancias con el propósito.

Los adolescentes notan problemas de manera diferente a los adultos porque experimentan frustraciones únicas, desde los desafíos de las organizaciones escolares hasta las redes sociales hasta las preocupaciones ambientales. Según la investigación de Square sobre empresarios de la Generación de la Generación Z, el 84% planea ser dueños de negocios dentro de cinco años, lo que los convierte en candidatos ideales para las empresas de resolución de problemas.

2. El aviso de chatgpt de chatgpt de chatgpt de realidad de la realidad del recurso

“Soy [age] años con aproximadamente [dollar amount] invertir y [number] Horas por semana disponibles entre la escuela y otros compromisos. Según estas limitaciones, ¿cuáles son tres modelos de negocio que podría lanzar de manera realista este verano? Para cada opción, incluya costos de inicio, requisitos de tiempo y los primeros tres pasos para comenzar “.

Este aviso se dirige al elefante en la sala: la mayoría de los empresarios adolescentes tienen dinero y tiempo limitados. Cuando un empresario de 16 años emplea este enfoque para evaluar un concepto de negocio de tarjetas de felicitación, puede descubrir que pueden comenzar con $ 200 y escalar gradualmente. Al ser realistas sobre las limitaciones por adelantado, evitan el exceso de compromiso y pueden construir hacia objetivos de ingresos sostenibles.

Según el informe de Gen Z de Square, el 45% de los jóvenes empresarios usan sus ahorros para iniciar negocios, con el 80% de lanzamiento en línea o con un componente móvil. Estos datos respaldan la efectividad de la planificación basada en restricciones: cuando funcionan los adolescentes dentro de las limitaciones realistas, crean modelos comerciales más sostenibles.

3. El aviso de chatgpt del simulador de voz del cliente

“Actúa como un [specific demographic] Y dame comentarios honestos sobre esta idea de negocio: [describe your concept]. ¿Qué te excitaría de esto? ¿Qué preocupaciones tendrías? ¿Cuánto pagarías de manera realista? ¿Qué necesitaría cambiar para que se convierta en un cliente? “

Los empresarios adolescentes a menudo luchan con la investigación de los clientes porque no pueden encuestar fácilmente a grandes grupos o contratar firmas de investigación de mercado. Este aviso ayuda a simular los comentarios de los clientes haciendo que ChatGPT adopte personas específicas.

Un adolescente que desarrolla un podcast para atletas adolescentes podría usar este enfoque pidiéndole a ChatGPT que responda a diferentes tipos de atletas adolescentes. Esto ayuda a identificar temas de contenido que resuenan y mensajes que se sienten auténticos para el público objetivo.

El aviso funciona mejor cuando se vuelve específico sobre la demografía, los puntos débiles y los contextos. “Actúa como un estudiante de último año de secundaria que solicita a la universidad” produce mejores ideas que “actuar como un adolescente”.

4. El mensaje mínimo de diseñador de prueba viable chatgpt

“Quiero probar esta idea de negocio: [describe concept] sin gastar más de [budget amount] o más de [time commitment]. Diseñe tres experimentos simples que podría ejecutar esta semana para validar la demanda de los clientes. Para cada prueba, explique lo que aprendería, cómo medir el éxito y qué resultados indicarían que debería avanzar “.

Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a adoptar la metodología Lean Startup sin perderse en la jerga comercial. El enfoque en “This Week” crea urgencia y evita la planificación interminable sin acción.

Un adolescente que desea probar un concepto de línea de ropa podría usar este indicador para diseñar experimentos de validación simples, como publicar maquetas de diseño en las redes sociales para evaluar el interés, crear un formulario de Google para recolectar pedidos anticipados y pedirles a los amigos que compartan el concepto con sus redes. Estas pruebas no cuestan nada más que proporcionar datos cruciales sobre la demanda y los precios.

5. El aviso de chatgpt del generador de claridad de tono

“Convierta esta idea de negocio en una clara explicación de 60 segundos: [describe your business]. La explicación debe incluir: el problema que resuelve, su solución, a quién ayuda, por qué lo elegirían sobre las alternativas y cómo se ve el éxito. Escríbelo en lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría “.

La comunicación clara separa a los empresarios exitosos de aquellos con buenas ideas pero una ejecución deficiente. Este aviso ayuda a los adolescentes a destilar conceptos complejos a explicaciones convincentes que pueden usar en todas partes, desde las publicaciones en las redes sociales hasta las conversaciones con posibles mentores.

El énfasis en el “lenguaje de conversación que un adolescente realmente usaría” es importante. Muchas plantillas de lanzamiento comercial suenan artificiales cuando se entregan jóvenes fundadores. La autenticidad es más importante que la jerga corporativa.

Más allá de las indicaciones de chatgpt: estrategia de implementación

La diferencia entre los adolescentes que usan estas indicaciones de manera efectiva y aquellos que no se reducen a seguir. ChatGPT proporciona dirección, pero la acción crea resultados.

Los jóvenes empresarios más exitosos con los que trabajo usan estas indicaciones como puntos de partida, no de punto final. Toman las sugerencias generadas por IA e inmediatamente las prueban en el mundo real. Llaman a clientes potenciales, crean prototipos simples e iteran en función de los comentarios reales.

Investigaciones recientes de Junior Achievement muestran que el 69% de los adolescentes tienen ideas de negocios, pero se sienten inciertos sobre el proceso de partida, con el miedo a que el fracaso sea la principal preocupación para el 67% de los posibles empresarios adolescentes. Estas indicaciones abordan esa incertidumbre al desactivar los conceptos abstractos en los próximos pasos concretos.

La imagen más grande

Los emprendedores adolescentes que utilizan herramientas de IA como ChatGPT representan un cambio en cómo está ocurriendo la educación empresarial. Según la investigación mundial de monitores empresariales, los jóvenes empresarios tienen 1,6 veces más probabilidades que los adultos de querer comenzar un negocio, y son particularmente activos en la tecnología, la alimentación y las bebidas, la moda y los sectores de entretenimiento. En lugar de esperar clases de emprendimiento formales o programas de MBA, estos jóvenes fundadores están accediendo a herramientas de pensamiento estratégico de inmediato.

Esta tendencia se alinea con cambios más amplios en la educación y la fuerza laboral. El Foro Económico Mundial identifica la creatividad, el pensamiento crítico y la resiliencia como las principales habilidades para 2025, la capacidad de las capacidades que el espíritu empresarial desarrolla naturalmente.

Programas como WIT brindan soporte estructurado para este viaje, pero las herramientas en sí mismas se están volviendo cada vez más accesibles. Un adolescente con acceso a Internet ahora puede acceder a recursos de planificación empresarial que anteriormente estaban disponibles solo para empresarios establecidos con presupuestos significativos.

La clave es usar estas herramientas cuidadosamente. ChatGPT puede acelerar el pensamiento y proporcionar marcos, pero no puede reemplazar el arduo trabajo de construir relaciones, crear productos y servir a los clientes. La mejor idea de negocio no es la más original, es la que resuelve un problema real para personas reales. Las herramientas de IA pueden ayudar a identificar esas oportunidades, pero solo la acción puede convertirlos en empresas que importan.

Noticias

Chatgpt vs. gemini: he probado ambos, y uno definitivamente es mejor

Precio

ChatGPT y Gemini tienen versiones gratuitas que limitan su acceso a características y modelos. Los planes premium para ambos también comienzan en alrededor de $ 20 por mes. Las características de chatbot, como investigaciones profundas, generación de imágenes y videos, búsqueda web y más, son similares en ChatGPT y Gemini. Sin embargo, los planes de Gemini pagados también incluyen el almacenamiento en la nube de Google Drive (a partir de 2TB) y un conjunto robusto de integraciones en las aplicaciones de Google Workspace.

Los niveles de más alta gama de ChatGPT y Gemini desbloquean el aumento de los límites de uso y algunas características únicas, pero el costo mensual prohibitivo de estos planes (como $ 200 para Chatgpt Pro o $ 250 para Gemini Ai Ultra) los pone fuera del alcance de la mayoría de las personas. Las características específicas del plan Pro de ChatGPT, como el modo O1 Pro que aprovecha el poder de cálculo adicional para preguntas particularmente complicadas, no son especialmente relevantes para el consumidor promedio, por lo que no sentirá que se está perdiendo. Sin embargo, es probable que desee las características que son exclusivas del plan Ai Ultra de Gemini, como la generación de videos VEO 3.

Ganador: Géminis

Plataformas

Puede acceder a ChatGPT y Gemini en la web o a través de aplicaciones móviles (Android e iOS). ChatGPT también tiene aplicaciones de escritorio (macOS y Windows) y una extensión oficial para Google Chrome. Gemini no tiene aplicaciones de escritorio dedicadas o una extensión de Chrome, aunque se integra directamente con el navegador.

(Crédito: OpenAI/PCMAG)

Chatgpt está disponible en otros lugares, Como a través de Siri. Como se mencionó, puede acceder a Gemini en las aplicaciones de Google, como el calendario, Documento, ConducirGmail, Mapas, Mantener, FotosSábanas, y Música de YouTube. Tanto los modelos de Chatgpt como Gemini también aparecen en sitios como la perplejidad. Sin embargo, obtiene la mayor cantidad de funciones de estos chatbots en sus aplicaciones y portales web dedicados.

Las interfaces de ambos chatbots son en gran medida consistentes en todas las plataformas. Son fáciles de usar y no lo abruman con opciones y alternar. ChatGPT tiene algunas configuraciones más para jugar, como la capacidad de ajustar su personalidad, mientras que la profunda interfaz de investigación de Gemini hace un mejor uso de los bienes inmuebles de pantalla.

Ganador: empate

Modelos de IA

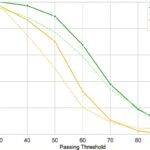

ChatGPT tiene dos series primarias de modelos, la serie 4 (su línea de conversación, insignia) y la Serie O (su compleja línea de razonamiento). Gemini ofrece de manera similar una serie Flash de uso general y una serie Pro para tareas más complicadas.

Los últimos modelos de Chatgpt son O3 y O4-Mini, y los últimos de Gemini son 2.5 Flash y 2.5 Pro. Fuera de la codificación o la resolución de una ecuación, pasará la mayor parte de su tiempo usando los modelos de la serie 4-Series y Flash. A continuación, puede ver cómo funcionan estos modelos en una variedad de tareas. Qué modelo es mejor depende realmente de lo que quieras hacer.

Ganador: empate

Búsqueda web

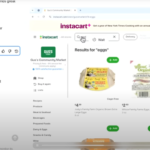

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden buscar información actualizada en la web con facilidad. Sin embargo, ChatGPT presenta mosaicos de artículos en la parte inferior de sus respuestas para una lectura adicional, tiene un excelente abastecimiento que facilita la vinculación de reclamos con evidencia, incluye imágenes en las respuestas cuando es relevante y, a menudo, proporciona más detalles en respuesta. Gemini no muestra nombres de fuente y títulos de artículos completos, e incluye mosaicos e imágenes de artículos solo cuando usa el modo AI de Google. El abastecimiento en este modo es aún menos robusto; Google relega las fuentes a los caretes que se pueden hacer clic que no resaltan las partes relevantes de su respuesta.

Como parte de sus experiencias de búsqueda en la web, ChatGPT y Gemini pueden ayudarlo a comprar. Si solicita consejos de compra, ambos presentan mosaicos haciendo clic en enlaces a los minoristas. Sin embargo, Gemini generalmente sugiere mejores productos y tiene una característica única en la que puede cargar una imagen tuya para probar digitalmente la ropa antes de comprar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Investigación profunda

ChatGPT y Gemini pueden generar informes que tienen docenas de páginas e incluyen más de 50 fuentes sobre cualquier tema. La mayor diferencia entre los dos se reduce al abastecimiento. Gemini a menudo cita más fuentes que CHATGPT, pero maneja el abastecimiento en informes de investigación profunda de la misma manera que lo hace en la búsqueda en modo AI, lo que significa caretas que se puede hacer clic sin destacados en el texto. Debido a que es más difícil conectar las afirmaciones en los informes de Géminis a fuentes reales, es más difícil creerles. El abastecimiento claro de ChatGPT con destacados en el texto es más fácil de confiar. Sin embargo, Gemini tiene algunas características de calidad de vida en ChatGPT, como la capacidad de exportar informes formateados correctamente a Google Docs con un solo clic. Su tono también es diferente. Los informes de ChatGPT se leen como publicaciones de foro elaboradas, mientras que los informes de Gemini se leen como documentos académicos.

Ganador: chatgpt

Generación de imágenes

La generación de imágenes de ChatGPT impresiona independientemente de lo que solicite, incluso las indicaciones complejas para paneles o diagramas cómicos. No es perfecto, pero los errores y la distorsión son mínimos. Gemini genera imágenes visualmente atractivas más rápido que ChatGPT, pero rutinariamente incluyen errores y distorsión notables. Con indicaciones complicadas, especialmente diagramas, Gemini produjo resultados sin sentido en las pruebas.

Arriba, puede ver cómo ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Géminis (segunda diapositiva) les fue con el siguiente mensaje: “Genere una imagen de un estudio de moda con una decoración simple y rústica que contrasta con el espacio más agradable. Incluya un sofá marrón y paredes de ladrillo”. La imagen de ChatGPT limita los problemas al detalle fino en las hojas de sus plantas y texto en su libro, mientras que la imagen de Gemini muestra problemas más notables en su tubo de cordón y lámpara.

Ganador: chatgpt

¡Obtenga nuestras mejores historias!

Toda la última tecnología, probada por nuestros expertos

Regístrese en el boletín de informes de laboratorio para recibir las últimas revisiones de productos de PCMAG, comprar asesoramiento e ideas.

Al hacer clic en Registrarme, confirma que tiene más de 16 años y acepta nuestros Términos de uso y Política de privacidad.

¡Gracias por registrarse!

Su suscripción ha sido confirmada. ¡Esté atento a su bandeja de entrada!

Generación de videos

La generación de videos de Gemini es la mejor de su clase, especialmente porque ChatGPT no puede igualar su capacidad para producir audio acompañante. Actualmente, Google bloquea el último modelo de generación de videos de Gemini, VEO 3, detrás del costoso plan AI Ultra, pero obtienes más videos realistas que con ChatGPT. Gemini también tiene otras características que ChatGPT no, como la herramienta Flow Filmmaker, que le permite extender los clips generados y el animador AI Whisk, que le permite animar imágenes fijas. Sin embargo, tenga en cuenta que incluso con VEO 3, aún necesita generar videos varias veces para obtener un gran resultado.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité a ChatGPT y Gemini a mostrarme un solucionador de cubos de Rubik Rubik que resuelva un cubo. La persona en el video de Géminis se ve muy bien, y el audio acompañante es competente. Al final, hay una buena atención al detalle con el marco que se desplaza, simulando la detención de una grabación de selfies. Mientras tanto, Chatgpt luchó con su cubo, distorsionándolo en gran medida.

Ganador: Géminis

Procesamiento de archivos

Comprender los archivos es una fortaleza de ChatGPT y Gemini. Ya sea que desee que respondan preguntas sobre un manual, editen un currículum o le informen algo sobre una imagen, ninguno decepciona. Sin embargo, ChatGPT tiene la ventaja sobre Gemini, ya que ofrece un reconocimiento de imagen ligeramente mejor y respuestas más detalladas cuando pregunta sobre los archivos cargados. Ambos chatbots todavía a veces inventan citas de documentos proporcionados o malinterpretan las imágenes, así que asegúrese de verificar sus resultados.

Ganador: chatgpt

Escritura creativa

Chatgpt y Gemini pueden generar poemas, obras, historias y más competentes. CHATGPT, sin embargo, se destaca entre los dos debido a cuán únicas son sus respuestas y qué tan bien responde a las indicaciones. Las respuestas de Gemini pueden sentirse repetitivas si no calibra cuidadosamente sus solicitudes, y no siempre sigue todas las instrucciones a la carta.

En el ejemplo anterior, solicité ChatGPT (primera diapositiva) y Gemini (segunda diapositiva) con lo siguiente: “Sin hacer referencia a nada en su memoria o respuestas anteriores, quiero que me escriba un poema de verso gratuito. Preste atención especial a la capitalización, enjambment, ruptura de línea y puntuación. Dado que es un verso libre, no quiero un medidor familiar o un esquema de retiro de la rima, pero quiero que tenga un estilo de coohes. ChatGPT logró entregar lo que pedí en el aviso, y eso era distinto de las generaciones anteriores. Gemini tuvo problemas para generar un poema que incorporó cualquier cosa más allá de las comas y los períodos, y su poema anterior se lee de manera muy similar a un poema que generó antes.

Recomendado por nuestros editores

Ganador: chatgpt

Razonamiento complejo

Los modelos de razonamiento complejos de Chatgpt y Gemini pueden manejar preguntas de informática, matemáticas y física con facilidad, así como mostrar de manera competente su trabajo. En las pruebas, ChatGPT dio respuestas correctas un poco más a menudo que Gemini, pero su rendimiento es bastante similar. Ambos chatbots pueden y le darán respuestas incorrectas, por lo que verificar su trabajo aún es vital si está haciendo algo importante o tratando de aprender un concepto.

Ganador: chatgpt

Integración

ChatGPT no tiene integraciones significativas, mientras que las integraciones de Gemini son una característica definitoria. Ya sea que desee obtener ayuda para editar un ensayo en Google Docs, comparta una pestaña Chrome para hacer una pregunta, pruebe una nueva lista de reproducción de música de YouTube personalizada para su gusto o desbloquee ideas personales en Gmail, Gemini puede hacer todo y mucho más. Es difícil subestimar cuán integrales y poderosas son realmente las integraciones de Géminis.

Ganador: Géminis

Asistentes de IA

ChatGPT tiene GPT personalizados, y Gemini tiene gemas. Ambos son asistentes de IA personalizables. Tampoco es una gran actualización sobre hablar directamente con los chatbots, pero los GPT personalizados de terceros agregan una nueva funcionalidad, como el fácil acceso a Canva para editar imágenes generadas. Mientras tanto, terceros no pueden crear gemas, y no puedes compartirlas. Puede permitir que los GPT personalizados accedan a la información externa o tomen acciones externas, pero las GEM no tienen una funcionalidad similar.

Ganador: chatgpt

Contexto Windows y límites de uso

La ventana de contexto de ChatGPT sube a 128,000 tokens en sus planes de nivel superior, y todos los planes tienen límites de uso dinámicos basados en la carga del servidor. Géminis, por otro lado, tiene una ventana de contexto de 1,000,000 token. Google no está demasiado claro en los límites de uso exactos para Gemini, pero también son dinámicos dependiendo de la carga del servidor. Anecdóticamente, no pude alcanzar los límites de uso usando los planes pagados de Chatgpt o Gemini, pero es mucho más fácil hacerlo con los planes gratuitos.

Ganador: Géminis

Privacidad

La privacidad en Chatgpt y Gemini es una bolsa mixta. Ambos recopilan cantidades significativas de datos, incluidos todos sus chats, y usan esos datos para capacitar a sus modelos de IA de forma predeterminada. Sin embargo, ambos le dan la opción de apagar el entrenamiento. Google al menos no recopila y usa datos de Gemini para fines de capacitación en aplicaciones de espacio de trabajo, como Gmail, de forma predeterminada. ChatGPT y Gemini también prometen no vender sus datos o usarlos para la orientación de anuncios, pero Google y OpenAI tienen historias sórdidas cuando se trata de hacks, filtraciones y diversos fechorías digitales, por lo que recomiendo no compartir nada demasiado sensible.

Ganador: empate

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoRemove.bg: La Revolución en la Edición de Imágenes que Debes Conocer

-

Tutoriales2 años ago

Tutoriales2 años agoCómo Comenzar a Utilizar ChatGPT: Una Guía Completa para Principiantes

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoStartups de IA en EE.UU. que han recaudado más de $100M en 2024

-

Startups2 años ago

Startups2 años agoDeepgram: Revolucionando el Reconocimiento de Voz con IA

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoCómo Empezar con Popai.pro: Tu Espacio Personal de IA – Guía Completa, Instalación, Versiones y Precios

-

Recursos2 años ago

Recursos2 años agoPerplexity aplicado al Marketing Digital y Estrategias SEO

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial Aplicada de 4Geeks Academy 2024

-

Estudiar IA2 años ago

Estudiar IA2 años agoCurso de Inteligencia Artificial de UC Berkeley estratégico para negocios